“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing. It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world.” The words were Donald Trump’s at a rally in Indiana; the subject was the United States’s trade deficit with China.

The language in which Trump chooses to frame America’s challenges is a large part of why Prospect-reading types recoil from him: again, Trump has gone beyond the pale. But it is arguably also a large part of what attracts his supporters. For there is a perspective from which the “rape” analogy, offensive as it is, captures their experience.

Listen to Trump’s rhetoric, and it cannily expresses a mix of feelings that are probably widespread within his core electoral fishing grounds: the white working class. He tells them they are being exploited by strangers (by foreign nations, through trade or immigration) and betrayed by those that should have protected them (their own nation’s elites, Republican or Democratic), with a devastating impact on their lives. Associating himself with this feeling of degradation and promising to fight those seen as responsible for it is, no matter how spontaneous it may seem, the carefully cultivated essence of Trump’s campaign.

The political as well as economic establishment shouldn’t have been blindsided by populists like Donald Trump: if many voters have turned anti-establishment, it was the establishment that abandoned them first. For too long, policymakers and economists ignored the high price paid by some for economic changes that were beneficial to most. Developments in global trade have harmed certain sections of western society, whose members were reassured that liberal free trade could only bring economic gains. In fact, with the broad gains came costs concentrated on some communities, and the damage done to local jobs has been more long-lasting than anticipated by traditional economics. Compounding the injury have been technological and political changes harming precisely the same communities.

Trump and his like will certainly do their supporters no good—but their hurt is real and their temptation to accept the snake oil on offer understandable.

The increase in inequality since about 1980, in the US in particular and in the rich world in general, has been felt for some time by those at the bottom. But it is only in recent years that, thanks to the Occupy movement and to the work of Thomas Piketty and his academic collaborators, the changed distribution of income and wealth has become firmly entrenched in the political consciousness of people at large, including those whom a more unequal economy may well have benefited.

But income inequality is only part of the story, for it is not only, or even mainly, material purchasing power that defines the complaints of Trump’s core constituency. It is something much more central to their sense of community, even of the meaning of their lives: work or, more precisely, its disappearance.

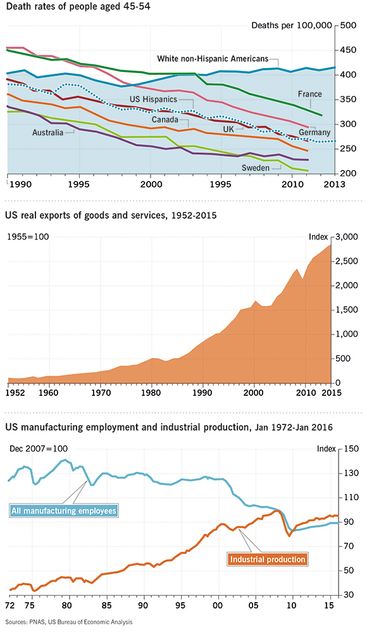

It is often said, not least by Trump, that trade has drained manufacturing out of the US. In fact, US industrial production has remained on a steady upward path, punctuated by drops during recessions followed by recoveries to the previous trend. The slide in 2008-09 was one of the biggest ever, and the recovery since has been unusually sluggish, but even at the depth of the global financial crisis US factories churned out twice as much stuff as they did in the early 1980s.

The difference is that they long ago stopped expanding employment. In each recession, US manufacturing has bled workers, and since the peak in the late 1970s, every recovery has re-employed fewer people than lost their jobs. Manufacturing never left the US; it was the manufacturing industry that left workers behind.

The biggest manufacturing job losses took place in this century, starting with the recession of 2001—one of the lightest in the postwar era—and continuing for several years into the new boom. For the first time, there was no upturn in US factory job numbers; the payroll kept edging downwards before slumping again as the global financial crisis hit. By the end of 2008, one-third of all the jobs in US manufacturing at the peak had gone, the bulk of them in less than a decade.

That double slide in the 2000s—through housing bubble and financial bust alike—coincided with another new phenomenon. In the first few months of the new millennium, the employment-to-population ratio of prime-age Americans—those aged between 25 and 54 years old and in work—hit an all-time record of 81.8 per cent. It would never again reach that point. It drifted steadily down, and only moved above the 80 per cent mark for a few months in 2007, on the back of a real estate bubble about to burst. Even today, the rate is more than 4 percentage points below the peak, amounting to some five million fewer prime-age Americans with jobs than would have been the case with the participation rate from the twilight of Bill Clinton’s presidency. Note “prime age”: this fall in activity is unrelated to young people struggling to get their first job or baby boomers hitting retirement.

The same number, five million, roughly matches the number of manufacturing jobs that have disappeared since 2000. Where did these factory workers go? The very sad fact is that too many of them, and the communities that relied on their work, went to rot.

Late last year, the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton (the latter fresh from winning the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences) shocked academics and policymakers by showing that mortality rates started rising among middle-aged working-class whites around the year 2000. This is more than an anomaly. For every other group and for all groups in other countries, mortality rates have continued to fall more or less uninterruptedly. After decades on the defensive, it is as if death itself has returned to haunt America’s white working class. And what were the causes of these increasing numerous premature deaths? Suicide. Alcohol and prescription drug poisoning. And chronic liver disease.

Something has clearly gone terribly wrong. But is trade to blame?

The two decades before the global financial crisis were, in retrospect, a heyday of global trade integration. Consider just the four biggest milestones. In 1993, Europe’s single market was launched. The following year, the North American Free Trade Agreement came into force. In 1995, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) was created, and with it the first permanent institution with powers to police global trade rules. And only six years later, China joined the WTO, setting off a stunning decade of economic growth powered by its tsunami of manufacturing exports throughout the world.

The degree to which they would transform global economic relationships was not missed by people at the time. After all, transformation was the point. So it may seem puzzling today that the actual economic consequences and the far worse political backlash were not foreseen. For the distributional effects of freer trade—and in particular, that unskilled labour loses out when a relatively skilled and capital-rich country lowers its trade barriers—are among the most basic lessons of the most conventional trade theory.

There were several reasons for this blind spot. The most important is easy to forget today: as the sun set on the 20th century, it was entirely natural to associate freer trade with greater fairness, prosperity and political harmony. That was, and remains, the key lesson of the two biggest disruptions in the global economy in the last 100 years.

The breakdown in trade relations and the global monetary system in the 1930s was rightly seen as having contributed to stagnant economies and antagonistic politics both among nations and within them. And the west’s golden era of growth after the war, which the French with unbeatable evocativeness call les trente glorieuses, was associated with the restoration of trade openness as part of a broader liberal international order and stable global monetary system. From 1955, the volume of US exports roughly doubled each of the ensuing four decades. Until the 1970s, that trade opening made the societies that took part in it—namely, the west—both more prosperous and more egalitarian.

A chief reason why this long, strong and steady restoration of trade links really lifted all boats is that cross-border commerce did not in fact follow the patterns of the classical theory. Ever since the 18th-century political economist David Ricardo, trade theory had predicted that a country would export the goods for which its particular resource endowment gave it a “comparative advantage” and importing different goods which it could only produce less efficiently at home with those same resources. (It is this recalibration of the use of different resources—labour and capital, for example, or skilled and unskilled labour—when trade opens up that leads to a change in the relative rewards they are paid.)

But much of the post-war growth in trade involved not comparative advantage based on relative resource endowments, but two-way exchanges of goods in the same industries—Germany and France both selling each other cars, for example.

Such “intra-industry trade” is hard to explain by comparative advantage, because it is not caused by relative resource endowments. It is caused by the existence of economies of scale and the fact that consumers like to choose from a variety of products from the same industry—you buy not just a car but a particular make and model. It is more efficient for countries to produce a few models and trade them back and forth than for each country to try to produce the entire range at home.

Only in the late 1970s did economists seek to develop models to analyse this sort of trade motivated by demand for variety and increasing returns to scale. Paul Krugman would later win the Nobel for his contributions to the new trade theory. One key implication was that trade integration need not have sinister distributional effects. This theoretical advance, together with the benign view of trade that 20th century history had taught, may explain some of the lack of elite concern.

Ironically, just as theory caught up, reality began to tilt back towards trading patterns driven by comparative advantage when developing countries, with very different endowments of human and capital resources than the rich world, increasingly entered international markets as transportation costs fell (due, for example, to container shipping). At almost exactly the same time, around 1980, inequality in the rich world began to increase in the direction classical trade theory would predict. An intense research programme followed, attempting to ascertain whether the cause was economic globalisation or the other potential culprit: technological change which favoured skilled workers over unskilled ones. By the late 1990s, just as the anti-globalisation protests were taking off, the economics profession settled on a consensus that technology more than trade was to blame.

"US manufacturing occupied an iconic place for the white working class. If they feel left behind, they have a point"Then China joined the World Trade Organisation.

The dislocation of millions of factory jobs described above followed, not just in the US but also in the UK (though to a lesser extent) and France (which, like the US, had already seen a decline for decades) and Canada (which had not). The blithe unconcern displayed by the economics profession and the political elites about whether trade was causing deindustrialisation, social exclusion and rising inequality has begun to seem Pollyannish at best, malicious at worst. Kevin O’Rourke, the Irish economist, and before him Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, have called this “the Davos lie.”

But economists have been catching up fast. David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson have been researching the effect of the “China shock” and in their paper The China Shock: Learning from Labour Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade, published in January in the US by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the trio of economists found that Chinese competition has localised, but substantial negative and long-lasting effects on the places particularly exposed to it. “Adjustment in local labour markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labour-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China shock commences,” the researchers write.

That shatters the widely held elite belief that the distributional consequences of trade are mild and manageable (but it may also explain the earlier persistence of that belief: the more localised the costs, the less noticeable to anyone else). It was long thought that the famously flexible US labour market would help people adjust to the disruption, by moving to where the jobs are. But as Autor, Dorn and Hanson show, China shocks have not been dispersed across the national economy. On one estimate, more than half of factory job losses can be attributed to the China effect. One reason may be that US workers have become less geographically mobile, perhaps in part because of the underwater mortgages the crisis left in its wake. That means the imbalanced effects of trade liberalisation can only be corrected if the losers are directly compensated out of the overall gain—but more redistribution and greater public goods provision are not on the cards in Trump’s deck.

Branko Milanovic, the inequality expert, has shown that in the two decades before the crisis, almost every income group in the world became better off, with one exception. Those around the 80th global percentile of income—who make more than about 80 per cent of the world population and less than the top 20 per cent—saw no improvement or even falling living standards. That’s right where the US white working class sits.

But misfortunes rarely come alone. While it now seems like trade liberalisation has indeed made this particular group worse off, that is only one of the calamities that have befallen them.

Another is technological change. Automation has meant that the bulk of the lost jobs over the past few decades were routine, low-skilled work. That includes both manual routine jobs (low-skilled manufacturing tasks) and cognitive routine ones (repetitive clerical work). Technology has thus helped drive a wedge between often well-paid non-routine cognitive work and usually low-paid service jobs where many of those losing their factory jobs to Chinese competition have been channeled. (And not only in the US; the same seems to have happened in Germany.)

A third factor is a change in power between capital and labour—and between high- and low-paid workers. The manufacturing industry was a source not just of good jobs for white blue-collar workers, but of social norms regarding how economic surplus should be shared. Robert Solow, the nonagenarian doyen of US economists, argues that the distribution of the fruits of productivity growth institutionalised by the car industry in the agreements known as the “Treaty of Detroit” served as a social contract for the US economy at large, according to which wages would grow in line with productivity.

But that social contract has been eroded: since the 1970s, US median wage growth has fallen far short of productivity growth. The distribution of market incomes has been tilted away from labour towards capital, and within labour income, it has been concentrated at the very top. The causes are many, but involve at least three things: market concentration which has reduced competition in many industries; a cultural acceptance of extravagantly high managerial pay; and a fall in unionisation.

Finally, economic security in the postwar years was buoyed by a set of welfare benefits put in place by the government or with government support during the New Deal and in the postwar demobilisation period, ranging from social security and mortgage subsidies to health insurance and college grants. There was a racist (and sexist) exclusivity about these—domestic and agricultural work, disproportionately done by black people (and women), were excluded from some of the schemes, and mortgage provision suffered from the discrimination of “redlining.”

Partly as a result of policy changes, partly as a result of demographic change, these benefits have become much thinner on the ground. Their erosion, then, disproportionately hurts the group that had benefited from it—white working-class male breadwinners—even as the slow rectification of past injustices benefits minorities. Recall the shocking rise in mortality for white Americans since 2000: mortality in fact remains higher among black Americans, but their rate has continued to fall. The “mortality gap” between blacks and whites is shrinking, but partly because whites are dying more than they used to.

"The trade and immigration shocks from the last wave of globalisation have been more disruptive than expected"So not only trade, but technology, distributive norms, and welfare policy together make a quadruple whammy that has badly knocked the economic security of the US white working class. That in turn has led to a crumbling of the physical health, mental well-being and social status of individuals and communities. Trade may only be one part of the cause, but it is the focal point of much of the understandable anger.

In its heyday US manufacturing occupied an iconic place in the aspirational cosmology of the white working class—think of the term “blue-collar aristocracy.” If they feel left behind by America, they have a point. It is no surprise that people feeling powerless and alone in the face of their demotion yearn to regain control—to “take their country back.” That is what Trump promises them.

The same dream of regaining control by déclassé groups fuels the growth of socially conservative nativist right-wing parties in Britain, France, Germany, Scandinavia and central Europe. And the insurgencies are not just on the right: in the US, Bernie Sanders speaks to some of the same grievances as Trump. Together they have helped make this campaign season unusually anti-trade, forcing Hillary Clinton to mark distance from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the recently concluded trade deal signed in February by 12 states, including the US, but which is not yet in force. It took seven years of negotiations to reach agreement on TPP—Clinton defended the deal while Secretary of State.

The most intriguing offshoot of the desire to “take back control” is the UK campaign to leave the EU. That is because while it appeals to the same emotional uncertainty as Trump’s presidential bid, the Brexit campaign cloaks it in an almost fanatically free-trade garb: the stated goal is to lower barriers with the rest of the world, to escape the walls of Fortress Europe. At the same time those who most strongly support Brexit are disproportionately hostile to immigration—as, of course, are Trump’s supporters.

The different attitude to trade makes little sense to economists, whose theories predict that the effect of low-skilled immigration is the same as of freer trade with countries that have a lot of low-skilled labour. In that sense, the Trump platform is more logically consistent than the Brexiteers.

But this is why the colourful Trump language with which we started is so revealing. At the deepest level, the anger on display on both sides of the Atlantic relates to disempowerment, demotion and a sense of being left behind on one’s own—as represented by an unsympathetic and overcontrolling bureaucracy. Causal complexity does not help articulate that frustration, which enables political entrepreneurs to channel it at obvious targets: trade with China and Mexican immigrants in the US; Brussels regulation and an influx of eastern Europeans in the UK. In both cases, the complaint is loss of control, the promise to take control back.

The problem is that framing the frustration in this way guarantees that it will not be mitigated. If “taking back control” means getting international rules off one’s back and a return to the economy of the past, it will not happen. Not just because globalisation is highly unlikely to be rolled back. But because the best hope even for those left behind lies in regulating it better.

Even at the domestic level, there is a reason for the many rules on economic activity. Put very simply, it is that the more complex the economy becomes, the more knowledge and information it takes for markets to work well. That, as Berkeley economist Brad DeLong has argued, means that the 21st century may well require bigger government and more intervention than the 20th century for our economies to be productive, let alone fair.

This is why Brexit would not lead to a bonfire of the regulations, but a redoubled effort to harmonise rules—that’s what trade openness increasingly means. It is also why TPP, and its US-EU cousin, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership are not primarily about tariff-cutting but about standard-setting and rule-making.

The trade and immigration shocks from the last wave of globalisation have been more uneven and disruptive than expected—economically, in the case of trade with China, and culturally, in the case of immigration. But both waves have mostly played themselves out. There will not be another China; and there will not be an EU enlargement to rival the absorption of formerly communist Europe. As for US manufacturing, since 2009 it has added almost a million jobs, more than in any recovery since 1983.

The rules for the evolving engagement of these economies, however, are still to play for. That point is largely missed in the cruder debates for or against trade or immigration. Deep distrust was sown by the elites’ slow realisation of the very real despair that grew in parallel with the benefits to many of economic change and globalisation. That distrust, unfortunately, makes it likely that, at best, our political systems will continue to host a dialogue of the deaf.