It’s been a difficult decade and a half in which to run a democracy. Two wars that did not go to plan—if I can put it like that—and a financial crisis that touched almost all the world have hardly helped build confidence in liberal democracies and free markets. My shelves are dominated by books of the “What went wrong?” genre: first a wave on Iraq and Afghanistan, giving way to a longer, higher swell of those on the crash and recession.

Debt, deficits, ageing populations, the impact of globalisation and technology on jobs and the stalling of productivity and wages all play a part. Threats and environmental problems proliferate and international alliances to combat them are wobbling. Above all, there is the new, angry scepticism of voters about their leaders, raising the spectre that democracy may be unable solve its own problems. For Prospect, these questions are its central preoccupation; the magazine was founded 21 years ago this year, and while it has never been attached to any political party, it early on borrowed the roll-your-sleeves-up spirit of the years that followed Tony Blair’s 1997 landslide.

The question of how Britain should combat such problems, abroad and at home, was the focus of an hour-long interview with Blair in Westminster on 24th May, just a month ahead of the European Union referendum and only a few weeks more from the publication of the Chilcot inquiry into Iraq.

The security that surrounds Blair even nine years after leaving office is not casual; guests are vetted, bags screened, access doors sealed off, his driver waiting throughout by a back door. Compared to Jeremy Corbyn, even to David Cameron, Blair has the air of a world-class politician used to addressing global audiences, albeit one who seems disconcerted by his disconnection now with the public life of his own country. Sitting on a stage under the baroque Edwardian ceiling of Methodist Central Hall in Westminster (“I’ve given so many talks here over the years,” Blair mused nostalgically in the corridors, looking around), the famous smile with the irregular teeth is still frequent; answers still begin with “Look...”, both casual and personal, which in more forgiving times would charm viewers from the television to the ballot box.

His answers were striking on two fronts. His call for military action—for boots on the ground—to defeat Islamic State (IS) in Syria made instant headlines. On foreign policy overall—including on Europe, where he is unsurprisingly a firm supporter of “Remain”—he argued as he had in office for Britain’s active involvement in the world, including for the use of military force.

His argument is a strong one, in my view, given the turmoil in the Middle East and the refugee crisis. Even on Iraq, some of his defence of his actions in office is well-founded, although his acknowledgement of lessons learned—that certainly does not approach an apology—is too breezy to match the scale of the failure.

Even more significant, however, was his comment that “I look at politics today and I’m not sure I understand it. I thought I was pretty good at politics,” he said. “But…I spend a lot of time at the moment trying to get my head around what’s really going on and how the centre—the centre left and centre right—seems to have lost its traction.” Laughing, he offered: “I’m thinking about it. When I discover the answer, I’ll tell you.”

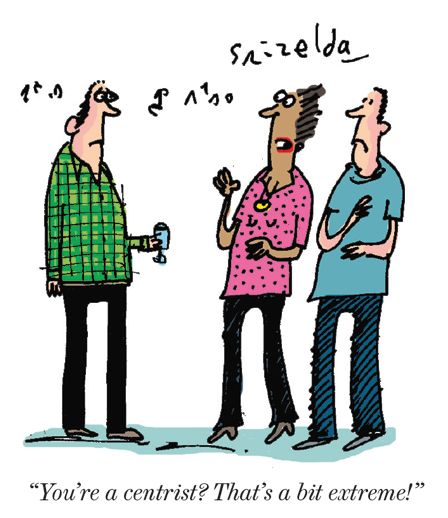

The rise of leaders from the extreme wings, whether Jeremy Corbyn’s triumph in the Labour Party, ousting the centrists of the Blair years, or Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and the far-right Freedom Party in Austria, is the political phenomenon of the moment. In any judgement of Blair, at least as important as Iraq is the question of whether voters still embrace the profound reforms that he set in train as part of his “government from the centre.”

They mostly do, it seems to me; they just don’t credit him as the architect. The pity of Blair’s legacy is that because of the enduring fury over Iraq, as well as because of the new many-sided anger against elites, many of the most valuable reforms he made in British life are taken for granted or forgotten.

Foreign policy dominates any question of Blair’s record, as it still dominates his life. The night before the Prospect event he had flown back from Israel, where he has, he says, devised an informal new role in trying to help Israeli-Palestinian talks restart through his relationships with the leaders. He cannot comment publicly on the results of the seven year Chilcot inquiry into the Iraq war (“not even raise an eyebrow”) before its 2.6m words are published on 6th July, but he is clearly preparing his riposte. He told Bloomberg in June that it was absurd for Corbyn to attack him as a “war criminal” for helping depose Saddam Hussein (as Corbyn did before becoming Labour leader) while Corbyn is praised as a “progressive icon” for resisting military action against Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad when his forces killed civilians.

The decision to join the United States in the 2003 invasion stands as one of the biggest failures of British policy abroad. The eight years of British military engagement led to the death of 179 personnel and cost at the time at least £9.6bn with more to come on veterans’ care, reckons the Royal United Services Institute think tank. At least 134,000 Iraqi civilians died. The US suffered the loss of 4,488 military lives, and the cost to the US has climbed to more than $2 trillion (studies put the combined US cost of the Iraq and Afghan wars at between $4 trillion and $6 trillion, close to a third of US national debt). Yet for all the hopes about instilling democracy, the result of deposing Saddam Hussein was a “winner takes all” frenzy—a government run by the Shia majority which promptly turned against the minority Sunnis, their former oppressors. Arguably, that sectarian fury led to the creation of IS, whose roots are in the Sunnis of Iraq’s Anbar province.

"Chilcot is thought to have stopped short of accusing Blair of lying to Parliament, a crucial point"Chilcot is reported to have criticised Blair strongly for the decision to join the US-led coalition. If so, that seems fair. Blair’s argument that he genuinely believed it the best course of action at the time should not be dismissed (and one former senior UK official put it to me recently “we were wrong [on the existence of weapons of mass destruction]. Plain wrong. But that is different from deceitful—and there are still those of us who think that the chemical weapons we know Saddam had will turn up in Syria.”) All the same, if not deceitful—and Chilcot is thought to have stopped short of accusing Blair of lying to parliament, a crucial point—the justifications were inadequate to the undertaking and distorted the evidence in public presentations.

At the time, Blair put enormous weight on joining the US in defending western values; Chilcot may shed useful light on whether, as some reports have it, President George W Bush told Blair several times that he would “understand” if Blair did not want to commit UK forces.

On the other hand, Chilcot is thought to have criticised British military generals heavily for accepting the prime role for the UK in running the south of Iraq; in 2007, besieged UK forces scrambled to extract themselves, to headlines “Brits run out of Basra.” Again, that verdict seems broadly fair, although in my view these were more understandable misjudgements than the UK’s eager and too hasty decision to assume responsibility for Afghanistan’s Helmand province in 2006, where military over-confidence clearly played a decisive part. In southern Iraq, in the early months after the invasion, when British troops were strolling around Basra in berets, little was understood about the sectarian fissures in Iraqi society. On one visit shortly after the invasion, I remember two British armoured vehicles patrolling a demonstration of tens of thousands of people in Basra, and thinking “there’s no way they are ‘keeping the peace.’” They weren’t; the powerful Shia cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani essentially was—and when peace no longer suited his supporters, it ended in a storm of roadside bombs and suicide blasts.

Looking back, the sectarian violence in 2005 is when those who hate Blair really started to do so. Of course, there were many who had protested over the invasion itself, on the grounds that the links with 9/11 were unproven and it had not passed the test for legal international action. Criticism swelled further when no nuclear, chemical or biological weapons were found. Even so, there were few critics of Blair who would actually have defended Saddam, given his record of killing his own people (with those chemical weapons, too). But the bombing by Sunni fighters of the Spiral Minaret of the Great Mosque in Samarra, a notable Shia shrine, in the spring of 2005 marked the point when sectarian tension began to boil over. The significance of the briefings about Iraq’s sectarian rifts which specialists had tried to press on the Bush and Blair teams became all too clear; the invasion had unleashed suppressed fury that would shatter the structure of any “representative democracy” which tried to contain it, with a rising civilian death toll as the inevitable result. Even though the “surge” of western troops in 2007 had some success in quelling the violence, the sense of “another Vietnam” had taken hold.

The Guardian reported on 6th June that Blair, in preparing his defence against Chilcot, is ready to argue that it was Iran’s entry into the conflict on the Shia side which helped make the situation uncontrollable, as well as the influence of al-Qaeda. That defence should not be dismissed either, but the threat should have been anticipated. Looking back, the really culpable mistakes were threefold: the exaggerated justifications for the war; the ignorance of the sectarian tensions which Saddam’s oppression had concealed; and naivety about what democracy would yield when the sectarian majority wanted not just to take all power but to kill the losing side.

A far longer war in Afghanistan and the Arab Spring have only strengthened the bitter knowledge about how little countries can help others that lack the basic structures of government. Confidence in “nation-building” has faded while disillusionment about development and aid has grown (a line of thinking which Prospect has covered extensively). The weary conclusion that it is easiest to help those who need it least is hard to resist.

That is why it is so striking that Blair, in speaking to Prospect, maintained that in Syria and Libya, only a military mission on the ground would defeat IS. “There is no way of defeating these people without defeating them on the ground. Airstrikes are not going to defeat IS, they have got to be tackled on the ground. It doesn’t mean to say it’s our forces all the time. Our forces can be in support. But do not be under any doubt at all. If you want to defeat these people you are going to have to go and wage a proper ground war against them and the only question for us is whether we are prepared to do that or not.”

It’s important to note that he was not talking about instilling democracy, simply about the use of military action to turn the course of a conflict, where he has a stronger point. He described Syria as “almost a problem without a solution” but remarked that if a deal could be brokered at all, that Russia now had the upper hand in determining whatever deal might be struck because of their deployment of military capability in the country. “The Russians are now a vital part of resolving this because they put leverage on the table. That’s just the reality. And we in the west I’m afraid decided that we weren’t prepared to do that.”

He also came close to criticising Cameron for not following through in Libya having acted to dislodge Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi as leader. “We cannot afford as Europe to have IS govern a large space of Libya. In the interests of our own security we are profoundly irresponsible if we allow this to happen.”

This unfashionable assertion about the need for military action does not mean that he dismisses diplomacy. He always had a barrister’s conviction that if you sat across a table and looked the other side in the eye, you could talk your way to a deal. But if that paid off in Northern Ireland, it has not so far in his self-fashioned role of interlocutor in Israel and the Palestinian territories where he is going about three times a month at the moment, he said—almost more often than in the nearly eight years he was UN envoy.

The special UN brief he accepted shortly before stepping down from Downing Street—to furious criticism from opponents of the Iraq war—was not for brokering peace, as many have assumed, but specifically for improving the Palestinian economy. He now acknowledges the discomfort of that role, saying “What I learned about the position I had was that if the politics aren’t right, the economics won’t work. You can take the economic changes to a certain level, but if you can’t then get the right political process in place it isn’t going to work... He concluded wryly: “The most dangerous thing you can ever do in politics is [to take] a position of responsibility without power.”

Asked whether British and American public antipathy was now a bar to the use of military force, he said that he acknowledged the impact of Iraq and Afghanistan (176 and 456 British military lives lost respectively) on public opinion. “For sure—we underestimated the scale of the problem. However, as you see from subsequent fields of conflict it’s not going to be easy whatever you do.” There are signs that the public mood may be softening slightly. When the Times revealed in May that British special forces were operating on the ground in Libya, and then that they were acting in Syria, there was nothing resembling a clamour to pull them out.

Yet the two wars have left a scar on foreign policy that will take many decades to fade, if it does. Together with an army sharply reduced in size from 102,120 full-time personnel in 2003 to 79,750 now, and the painful lessons about the limits of successful assistance to another country, they are a real bar on future significant military action by Britain abroad, which has constrained it both in Syria and on the immigration crisis.

Iraq overshadows the legacy of his project of reforming Britain—although his critics would add, so does the financial crisis which had at least some roots in his years in office. “I have never quite understood why my own party has not said very clearly that this [was] a global financial crisis,” he retorts. “You can argue about whether you might have tightened fiscal policy in around 2005 somewhat or not, but the fact is that every country in the western world was hit by this global financial crisis.”

"Many of the social reforms he initiated have taken root to the point where they are taken for granted"Many of the social and economic reforms he initiated have taken root and flourished to the point where they are taken for granted. Those include the removal of most hereditary peers from the House of Lords (although I remember one distinguished Saudi diplomat saying caustically at the time “If that’s what Tony Blair means by democracy—getting rid of one house of parliament and replacing it with his friends, we could do that tomorrow.”) It includes the creation of the Scottish and Welsh Assemblies and the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland; for that alone, he gets too little credit—for approaching it in the spirit that at the end of the 20th century, it was an embarrassment to have an unsettled conflict within the UK’s borders.

After early rejection of previous Conservative policies, the approaches he set in train on academy schools and NHS management have largely lasted. His government’s legislation on civil partnerships paved the way for gay marriage, now taken as the norm, a social revolution in itself in barely a couple of decades.

But while the independence of the Bank of England, one of his first actions, has persisted, the financial crisis exposed the severe weaknesses of bank regulation. The openness of markets—and borders—that he embraced is now under challenge, and international cooperation is faltering. Asked whether his government had let in too many immigrants by changing the rules on asylum, scrapping the “primary purpose” rule, one of the toughest constraints, and accepting immediate immigration from new EU members he said: “Personally I don’t. I know that there is a criticism, which I completely understand, that we shouldn’t have introduced earlier than [we had to] the free movement of people from Eastern Europe.

“I do think that we should take a step back and look at the big picture here,” he added. “The advent into the EU of the Eastern European countries is of huge strategic importance to Europe and the world and we should be proud of the fact we championed this.” The “free movement of people in Europe has been a net benefit,” he argued, adding that “I believe the people who have come into the country have contributed far more by way of taxes and by way of commitment and energy to this country than they have taken by way of benefits,” although saying “I understand that you have got to have controls on immigration, I fought the 2005 election on immigration.”

That is one reason why radical European politics perhaps now baffles him, given that much of it is driven by fears about immigration. And his own party is still grappling painfully with his legacy (see Jon Cruddas, p50) and with whether it needs to appeal to the centre ground; those who hold fast to that principle are at the moment consigned to the fringes. The Conservatives, though, are equally buffeted by Ukip from the right, and although Cameron aims to appeal to the centre in a way which echoes Blair, it does not seem an entirely secure stance.

The spectacle of British politics today barely resembles that of the Blair years; there is a roiling anger at the elites who led the country into two unsuccessful wars and who facilitated the financial crisis. Many feel they have lost out from the globalisation in which Blair has such faith. Populists are “riding the anger,” he retorts. “They’re not actually providing the answers. Suppose you go down the route of scrapping all the free trade stuff. The one thing I think that is absolutely clear from economic history is that’s a bad idea.”

Asked about Jeremy Corbyn, Blair said:“The basic elements that gave rise to [Blairism] are still there and let’s say it’s still not a proven concept that Corbynism can win an election.” Asked whether the Labour Party has already lost the next election, he said “No. I would never say that until it happens—if it happens.”

Some of the upheavals of the past decade and a half should be laid directly at the door of those then in charge. Chilcot, however cumbersome, is part of that, as is the lassoing of the banks with new loops of regulation. The extraordinary acknowledgement that the International Monetary Fund has just published about the effect of recent “rescue” policies on Greece—almost a “mea culpa” as one leader in the Financial Times put it—is part, too.

But some of those forces are now on a scale hard for any individual government to control or shape, certainly within the span of one electoral cycle. It is not new for countries to have debt and deficits, but it is new for them to try to remedy those with ageing populations and a boom in the proportion of those retired. That leads to the predicament I have called in Prospect “the bonfire of the promises” as governments are forced to tell voters that all the “contracts” they thought they had with their state, about healthcare and education and above all, about pensions—are being rewritten and not in their favour. And then they have to ask to be voted in again. This is a hard time to be in democratic politics.

Longevity alone is a force that should be a bonus—one of the great achievements of the past century is to have added up to four decades to the lifespans of Britons. But with working patterns and entitlements that currently exist, it is a burden. If countries don’t grapple with it, they will fall into traps one after the other, from Gordon Brown’s 1999 offer of a mere 75p rise in the weekly state pension, to the rescue terms for the Tata steel works that may, in effect, cast doubt over the security of the whole class of “defined benefit” pensions.

Meanwhile, the revolution in the world of work continues to offer promise although it threatens many jobs. The difficulty in coaxing a rise in productivity when it has barely shifted for decades has been described as the most serious economic problem of many countries, Britain and the US included. The failure of wages to rise much in real terms is a big reason why people are so angry at those who govern them.

It may be that those trends are reversing. In one of the most original and potentially prescient articles we have published in the past year, the economist Charles Goodhart, Manoj Pradhan and Pratyancha Pardeshi of Morgan Stanley argued that Thomas Piketty, in Capital, had failed to give enough credit to the demographic waves shaping the global workforce. The wave of workers from Central and Eastern Europe and China had depressed wages; now that had passed, wages might now rise again, the authors suggested.

"Blair was more comfortable than many voters with international alliances-Iraq came out of this instinct"Maybe. Even so, the scale of global forces operating on any one country makes it hard for an elected government to govern. Companies barely recognise the borders of the nation state never mind feel an obligation to pay tax to one; environmental threats are truly global. There are signs of international cooperation to combat these in what you might call coalitions of the willing: on the Iran nuclear deal, on the Paris climate change deal last year, to some extent on tax co-operation. But as the EU referendum in the UK has shown, many voters mistrust their own government yet they like even less for it to delegate authority to others.

Blair was always more comfortable than many voters with international alliances, and Iraq came out of exactly that instinct to strike up such pacts in personal conversations with other leaders. While some of Blair’s responses on Iraq are justified, ignorance is hardly a robust defence. We will in any case be in a better position to judge when Chilcot finally lands.

The pity of Blair’s position is that if it weren’t for Iraq, more of the astonishing social transformation of Britain and the change in its structures of government would be recognised. As it is, he is all but disqualified from British and European politics. The greater tragedy is that his arguments are disqualified along with him even when they are right. He is right, for instance, about the value of an active foreign policy in retaining an ability to shape events abroad, but Iraq (and Afghanistan) have made that understandably repellent to many. Even more than that: it is genuinely a hard time to run a country, and the kind of reforms from the centre ground, and international negotiations of exactly the kind which he advocates and at which he is undeniably skilled are important tools. But after the mistakes of the past 15 years, voters have had enough of their fortunes being signed away by political elites in private talks. His talents and most important ideas may be for the time being still too toxic to deploy.