It feels like a lifetime ago, but it was the first week of March. I still recall my shock, seeing the long shelves of my nearest hypermarket-sized Sainsbury’s empty of pasta. At first I assumed they were re-organising the aisles, or something equally mundane—until I overheard a conversation between two customers about “stockpiling.” The realisation dawned slowly—this is really happening.

Within days, many of us were doing a bit of panic buying, although we told ourselves we weren’t panicking, just buying. As the Covid-19 clouds gathered and darkened through the middle of March, I cycled between the largest supermarkets in south London to see which stocks were the first to go. To begin with, it was the store-cupboard staples disappearing—pasta, rice, pulses, tins of tomatoes—and then, a kind of retro-wartime rationing kit: flour, vegetable oil, eggs, tinned fish, tinned fruit, tea and coffee. As lockdown finally neared, fresh meat and vegetables started to empty out too, along with wine, beer, and bottled water. I peered in to read the label attached to an empty shelf in the Sydenham branch of Sainsbury’s: “Cherryade 2L.” A lesser-known preppers’ favourite.

Row after row of empty shelves greeted shoppers, and photos of the same circulated on social media, and were replicated across the nightly news—the images prompting more stockpiling, and a growing atmosphere of desperation and dismay. They were scenes we associated with failed states in faraway lands—recalling grainy footage of Russia in 1990 or Venezuela in 2016—with the collapse of communist planned economies, not the relaxed consumer utopias of the modern supermarket-state.

The supermarkets were jolted into action. On 15th March the “big four”—Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons, which hold 68 per cent of the grocery market between them—along with the second tier (M&S, Co-op, Waitrose, Iceland, Aldi, Lidl, Costcutter and Ocado) issued a joint statement. It promised they were working closely with their suppliers, offered reassuring words that they were in control, and asked that people shop responsibly. “Together we will care for those around us and those who are elderly, vulnerable or choosing to remain at home,” it concluded.

The letter was headed “Working To Feed The Nation” and carried the same paternalistic tone as a communiqué from the wartime Ministry of Food. And sure enough, the supermarkets began to establish rationing, limiting customers to three of each food item, and contacting vulnerable customers directly, allocating them specific shopping times—taking charge as you would expect government to do in a crisis. They did their own contingency planning and even emergency “simulation exercises”—a sort of shadow “Cobra.”

They began to act like political operators too, and effective ones at that. In the early days of the crisis, one supermarket executive gave an anonymous briefing against the government, suggesting to the BBC that the state was not on top of the supply chain. The big four followed this up by throwing their weight around further, demanding a relaxation of competition law that would allow them to co-ordinate supplies, deliveries and opening hours. The government, sitting quietly in the sidecar, duly acquiesced. “We’ve listened to the powerful arguments of our leading supermarkets and will do whatever it takes to help them feed the nation,” responded Environment Secretary George Eustice.

Along with public health and economic impact, the question of how we feed ourselves has become the third great meta-issue of this crisis. Is it good enough to leave the fate of vulnerable people to the vicissitudes of the market, and the goodwill of a handful of retailers—or are empty shelves and bare cupboards problems that demand co-ordination at the national level? When did the British government abdicate responsibility for “feeding the nation,” and let the supermarkets take over from the state? When it comes down to it, who is in charge of our food security?

"Empire would provide"

The resilience of our food systems has been an issue for as long as governments have existed—protecting supplies and imports was, for example, one of the fundamental duties of the Ecclesia of ancient Athens. And no wonder. Being sure you can feed civilians has always been a (literally) vital consideration. This is true in good times as well as bad, but public health crises and wars serve to sharpen the focus.

Coronavirus has revealed that our own food system is “risky, over-stretched, and much more fragile than you’d think,” says Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City University and author of Feeding Britain, published with perfect timing in March. It’s a situation he argues has its roots in centuries of imperial complacency. “The assumption was always that the empire would provide. We still haven’t got over the idea that someone else will feed us—we saw it with Michael Gove and Liam Fox in the EU referendum campaign: don’t worry, Africa or America will feed us. It’s incredibly cavalier.”

A former Lancashire hill farmer and a treasure trove of food history, Lang tells me that the first ship carrying New Zealand lamb and mutton to the UK arrived in 1882. Even before that grain was flowing in from the newly-opened American prairies, cheaply feeding hungry mouths in the cities, at the cost of the so-called “long depression” on British farms. As Victorian Britain industrialised, urbanised and prospered, those who were content to rely on foreign commerce for cheap food had the better of the argument: when, for example, the Liberals hailed the “large loaf” of free trade in 1906, they cleaned up at the ballot box. And colonial ties to big producers including Australia and Canada as well as New Zealand made it look like the sun could never set on the global markets that nourished the country.

“We saw it with Michael Gove and Liam Fox in the EU referendum campaign: don’t worry, Africa or America will feed us”

But the First World War provided a wake-up call, with submarines threatening the imperial supply lines. A Ministry of Food was established in 1916, to the dismay of the food industry. But as soon as the war was over, it was dismantled—it was time to return to “business as usual,” in the words of the secretary of state for war, Viscount Milner. “That ‘business as usual’ was played out in the 1920s and 30s,” Lang says. “Mass hunger, farming in complete collapse, and a total lack of self-sufficiency.”

British self-sufficiency fell to just 33 per cent in the 1930s—the lowest in its history—and a Nazi blockade of the British isles would bring the country to its knees. Only a massive effort during the “phoney war” of 1939-40—the rationing and land armies, the diktats to farmers over what crops to grow, the whole nation digging for victory—doubled that food production figure and allowed Britain to avert mass starvation.

This mid-century period of “war socialism” saw the British state take charge of food with tremendous vigour—witness the austerity wartime recipe books in museum gift shops, alongside the famous Dig For Victory posters. Schoolchildren learn about the mobilisation of the Women’s Land Army and the hardships of rationing (and, thanks to post-war austerity and then fighting in Korea, anyone sentient before 1954 will remember it). Churchill’s wartime government even established 2,000 British Restaurants, which served hundreds of thousands of subsidised meals every day to make sure everyone was fed healthily, before being disbanded in 1947.

Even after the dismantling of the second Ministry of Food in 1955, the state remained much more involved in emergency food planning than it is today. During the Cold War, Second World War stockpiles were maintained in dozens of substantial “buffer depots,” corrugated iron warehouses and silos, to be distributed to the survivors of nuclear attack. Vast supplies of frozen, dried and tinned food were stored in secure locations around the country, including flour, yeast, sugar, biscuits, boiled sweets, dried egg and fat (“ministry marge,” with a shelf life of 20 years). Meanwhile, the government’s infamous “Protect and Survive” advice booklet recommended that households stock enough food to last 14 days.

With little fanfare, the final food stockpiles and buffer depots were disposed of in 1995. In total, the government still held 200,000 tonnes of food at this point—four decades after the end of rationing, and several years after the fall of the Soviet Union. It was a change that reflected the end of the Cold War, but also a period in which supermarket hegemony was ramping up.

Just in time, just enough

With their tendency to historicise their “humble grocer” origins in black and white—Sainsbury’s made a great show of celebrating its 150th birthday last year—it’s easy to forget that the rise of the supermarkets was relatively recent. While already a substantial part of American food consumption before the Second World War, this radical new kind of self-service shopping did not take off in Britain, where grocers were still overwhelmingly found behind counters, until after rationing ended: the number of supermarkets rose from just 50 in 1950 to 572 by 1961, and over 3,000 by the end of the 1960s.

In the decades that followed, they didn’t just continue to spread, but conquered all before them. They branched out into banking, petrol, clothing, telecoms and energy. They battled with local community groups and independent traders for the right to build massive edge-of-town hypermarkets—sometimes losing, often winning. They took over not just the supply of our daily bread, but our high streets and—through mergers that have built substantial monopolies—each other.

There is one particular change in the way that supermarkets operated that explains both their total market dominance, and the shocking sight of empty shelves that occurred in early March. It is the ascendance of the “just in time, just enough” supply chain since the 1970s. Just-in-time stipulates that businesses sell off any warehouses, and ideally carry no stock whatsoever—it is a strategy that originated with Toyota’s car manufacturing process, but then spread to our food supply. The result is a complex chain of farmers, processors, packagers and transporters, where the imperative is seamless efficiency—driving costs down to a bare minimum, with produce ever cheaper.

The benefits of this system are familiar to us, as they are ingrained in our everyday lives: round-the-clock, round-the-calendar availability of any produce we want, and often at low prices. Our food is the cheapest in western Europe, and as a proportion of household income, our spending on it has halved since the 1960s. It is the market utopia in action: where the public good is defined in terms of cutting the price to the consumer, with strawberries at Christmas as a bonus.

The problem is that the just-in-time food supply doesn’t just minimise cost, it minimises resilience. There is only a few days’ worth of stock in the UK’s food distribution chain. One act of god or political shock, one unexpected drought, coup, oil spill, terrorist attack, conflict or strike—one domino removed from the run—and everything can grind to a halt.

“The supermarkets have no storage, because the storage is on the motorway,” says Lang, referring to the lorries delivering to stores. “If you apply a military or defence analysis to that situation, that is incredibly easy to disrupt.” The complexity of the just-in-time food system only magnifies its vulnerabilities—such that a butterfly effect can ripple outwards in the most unexpected fashion. The closure of several European fertiliser plants for routine maintenance in 2018 led to a shortage of carbon dioxide in storage, which is essential to much food and drink manufacturing (carbon dioxide is a byproduct of that fertiliser production). “Will we run out of beer and meat?,” a headline on the BBC News site asked plaintively at the time.

The spectre of Brexit

Things could have been worse. Preparing for Brexit, and especially the possibility of a disruptive no-deal Brexit, meant—or should have meant—that Britain’s food system was in a good place for the unprecedented shock of Covid-19. After all, and extremely unusually, we have been worrying about supply lines, food shortages and panic buying in the last couple of years.

Since 2018, for the first time since the era of rationing, Britain has had a dedicated food supplies minister. A year later, Henry Dimbleby, founder of Leon, was asked to head up the first independent food system review for 75 years. Dimbleby’s team spent six months gathering a broad sweep of evidence, from chefs, farmers, nutritionists and environmentalists, and was due to publish its findings in a landmark National Food Strategy this summer.

That strategy is now more needed than ever. “One thing I hope will come out of this is we will all have the imagination to be able to engage with these really big, existential problems,” Dimbleby tells me. “But the risk is that we see this crisis as every crisis: other shocks might look very different—for example, what we haven’t had with Covid is any failure of harvest.”

One lesson from the empty shelves, he continues, is that spare capacity in our food supply is a good thing, provided it is sustainable: “Prepare for war while you’re at peace. The issue is that spare capacity in the food system looks like food waste. One way to deal with that in the past has been to export it. But I think you could make an argument that some of that spare capacity should be in the form of food mountains, the stockpiles of food that became so unpopular in the 1980s.”

Like Lang, Dimbleby is fond of talking about the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, and the rapid decline in British agriculture that followed, along with the crises of the late 1930s, when German U-boats had the potential to starve Britain into surrender; about the vulnerabilities that come from being too reliant on our own crops, and conversely, too reliant on those of other nations. “Notwithstanding the fact that those global channels make our system more robust, we are now seeing how important our farmers and our food production are to us. Ideally, the most secure food system would be one that is growing a lot, exporting a lot and importing a lot, because it gives you so many options.”

“We face the threat of thousands of dairy farmers going under, and once they’re gone, you can’t get them back”

Planning for this sort of balance in the supply sounds like common-sense pragmatism, but the laissez-faire alternative of letting the market rip has deep roots in this country, and retains influence close to the top. As recently as February, reported remarks from a senior government adviser that the food sector “certainly isn’t” of critical importance to the UK economy made front-page news; his observation that Singapore had got “rich without having its own agricultural sector” added extra spice, and—for Britain’s embattled farmers—outrage.

Food libertarians can argue that the shortages have proved transient, just like the supermarkets promised. They can point to the way that—despite the desperate circumstances—the shelves are restocked without prices rocketing, and generally marvel at the way that just-in-time just about got us through. But the food crisis is not over. India and Vietnam have suspended the signing of new contracts for rice exports. Spain, the provider of so many of our citrus fruits, kiwi fruits and vegetables, is without its usual labour force from Morocco and Algeria.

Meanwhile British farming faces its own massive labour shortfall—as of 2018, 99 per cent of seasonal agricultural workers come from the EU—which could see crops wither on the vine. An emergency charter flight of fruit-pickers has arrived from Romania, but the proposed native “land army” has failed to materialise, despite pleas from the government. There just doesn’t seem to be the will—still less the experience or logistical support—to pull off a contemporary “dig for victory.”

“We’ve seen the really hard work, the inventiveness and resilience of Britain’s food industry in coming up with ways to suddenly gear up production, almost overnight,” says Adam Leyland, editor of industry bible The Grocer. “But there are some really struggling suppliers out there, and some of what’s going on is very much ‘business as usual.’ What we’re facing, for example, is the loss of our dairy supply chain. And the government’s response to date has been like a rabbit in the headlights.”

With about half of the UK milk supply usually going to food service and hospitality, dairy farmers have already been forced to dump tens of thousands of gallons of milk down the drain, with the National Farmers’ Union warning of the need to avert a “national catastrophe,” following crisis talks with MPs in mid-April. “We face the threat of thousands of dairy farmers going under,” says Leyland, “and once they’re gone, you can’t get them back—you can’t just mothball a cow.”

Glitch in the system

The destiny of nations depends on the manner in which they are fed,” the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin wrote two centuries ago. One point that bears spelling out is that food security isn’t just about shipping containers and logistics spreadsheets, tariffs, trade and industry; it is not just about the processes whereby food gets from farm to table—but about public health, inequality, food education and poverty too.

Food banks are part of this discussion, and—seeing as the question is not just the volume of available food, but also the quality—so is obesity. Even before Covid-19 and before the EU referendum, millions of British people were struggling to feed themselves and their families, let alone to do so healthily.

“The so-called normal situation was riddled with fissures,” says Lang. “Millions fed by food banks. Farmers kept alive by subsidies. It was never sustainable.” He proposes dramatically rewriting the agriculture bill currently going through parliament, to prioritise food as a primary goal—apart from anything else, for environmental reasons: the Zero Carbon Britain study says that we should double the amount of land used for growing food, in order to reach net zero. “We need a total re-engineering of our food system to build in social resilience and ecosystem resilience—this is not a one-off crisis, it’s a rolling problem. Government has a responsibility to feed the nation, and they’re literally saying ‘the retailers will sort it.’ It’s staggering.”

For now, the shelves in my local supermarkets seem mostly stacked as normal, but even in the short term, that does not mean everything is fine. Food banks across the country are reporting a simultaneous surge in demand, and a substantial shortfall in donations as well as a dwindling of (often retired) volunteers. Economic depression and social isolation are combining to create hunger. Only three weeks into the lockdown, research by YouGov for the Food Foundation found that 1.5m British people had had to go a whole day without food.

Aware of their newfound role as designated first responders—and following an unprecedented boost to their sales—Morrisons donated £10m of groceries to food banks, Co-op donated £1.5m, Tesco announced a £30m Covid-19 Community Fund (including £15m for food banks), and Lidl handed out free fruit and vegetables to NHS staff. The government could only respond to the Food Foundation poll on mass hunger with words of concern, and imprecise promises to work with partners and “ensure essential items are delivered to the most vulnerable.”

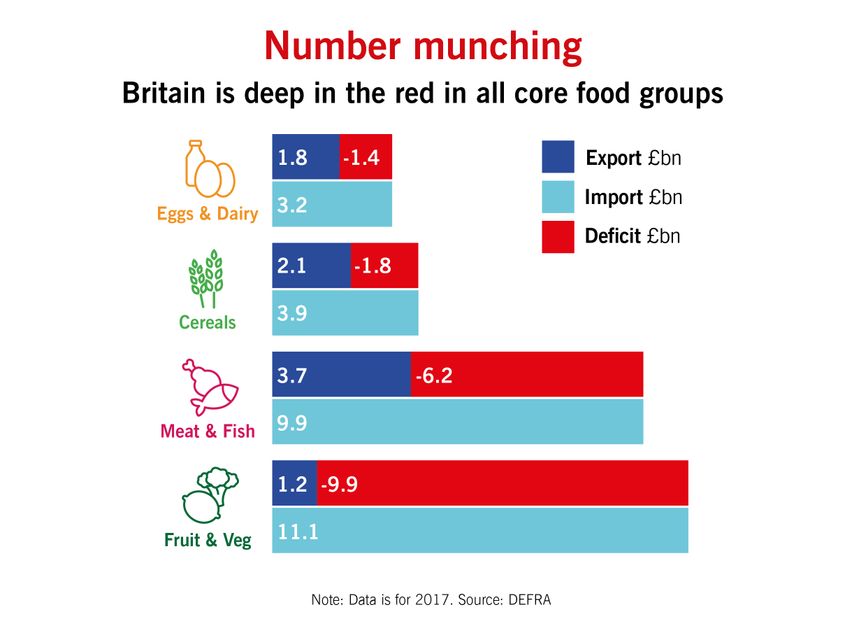

Whatever becomes of the legislation that’s promised to follow the National Food Strategy, when the dust settles this government will have an unprecedented opportunity—and a need unmatched since the 1930s—to overhaul the British food system. After rising steadily post-war, Britain’s self-sufficiency in food has been falling since the 1980s, and is now back down to 50 per cent, according to the department for environment, food and rural affairs.

Millions of Brits are reliant on charity from concerned citizens—topped up by PR-conscious supermarkets. Our farming is in a near-permanent state of crisis, even without Brexit, and climate change threatens many of the sources of food imports on which we have relied. From supply logistics to feeding our most vulnerable, the state has left it to the supermarkets for decades, and the results of its absconsion are panic and hunger.

When the aisles stood empty in March, it was not just a shock, but an epiphany. The full supermarket shelves we are used to seeing—the set-dressing of our everyday lives—suddenly looked like Potemkin facades of capitalist abundance. One glitch and the whole “just in time, just enough” edifice began to crumble, and almost collapsed. The fragilities of our food system were laid bare. Next time, we won’t be able to say that we didn’t know.