Few historians’ lives were as dramatic as Eric Hobsbawm’s. As Richard J Evans charts in his generally admiring Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History (Little, Brown), the Marxist’s loyalties were forged in the ideological battleground of 1930s Germany. After moving to England, he swiftly became a star of post-war history but never left the Communist Party. He knew his first marriage was in trouble, Evans says, when his wife gave him Nineteen Eighty-Four for Christmas.

Simone de Beauvoir’s personal life—especially her relationship with Sartre—often overshadows her philosophy. Kate Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir (Bloomsbury) puts that right. Her version of existentialism escapes the charge of excessive individualism: no one becomes themselves alone. Another philosopher whose life was intertwined with their thought is Kierkegaard. In Clare Carlisle’s Philosopher of the Heart (Allen Lane), he is shown as an anguished rebel kicking against the bourgeois conformity of his native Denmark. Someone often compared to Kierkegaard is Socrates. Armand D’Angour’s concise portrait, Socrates in Love (Bloomsbury), says that his philosophy was influenced by a “wise woman” called Aspasia—Pericles’ wife—who was his “instructor in love.” D’Angour’s Socrates is a man of flesh and blood, fond of dancing, wrestling and romance.

Bauhaus guru Walter Gropius also had an energetic love life. Fiona MacCarthy’s Walter Gropius (Faber) conducts us from his affluent childhood in Berlin to his involvement in progressive design groups. The emotional heart, though, is his turbulent relationship with the composer and socialite Alma Mahler, a libertine, snob and anti-semite, beside whom Gropius can seem a trifle dull.

The women in Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five (Doubleday) are most famous for being Jack the Ripper’s victims. Rubenhold’s book, which won the Baillie Gifford Prize, movingly restores their humanity. Elisabeth Stride was born in Sweden, moved to London, faked a story about her family dying in a boat disaster, learned Yiddish after a Jewish family took her in as a servant, but was arrested for soliciting on Commercial Road. On the night of 29th September 1888, she was found murdered, with a rose pinned to her bonnet and breath-freshening sweets in her hand.

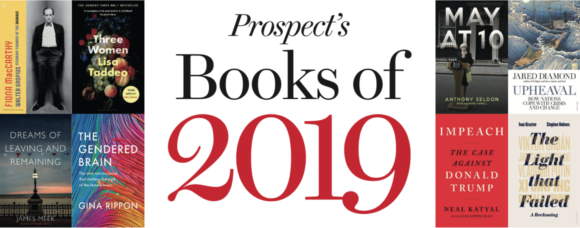

“Throughout history,” writes Lisa Taddeo in Three Women (Bloomsbury Circus), “men have broken women’s hearts in a particular way.” These stories of female exploitation—Lina was assaulted at school and then exploited by her teacher—are powerful but not helped by Taddeo’s overwrought prose.

Sophie Ratcliffe’s biblio-memoir The Lost Properties of Love (William Collins) is an ingeniously constructed tribute to messy relationships, roving between her teenage days, the early death of her father and a love affair with a charismatic older man. He once asked why she didn’t write something people might want to read. This is her eloquent reply. Homing (John Murray) by Jon Day is a dazzlingly erudite memoir about family, children and pigeon-fancying. An unlikely combination perhaps, but Day pulls it off.

Laura Cumming’s mother was kidnapped as a child. Unravelling why in the exquisite On Chapel Sands (Chatto & Windus) leads Cumming to uncover a once shameful family secret. Cumming, an art critic, draws out the meanings of the photos her grandfather George took with his Box Brownie: some snaps of her grandmother resemble Vermeers, one of the author’s passions.

As a child in Germany, Lucian Freud was given a copy of Grimm’s fairy tales by his grandfather Sigmund. The Lives of Lucian Freud by William Feaver (Bloomsbury) is full of such teasing details about the artist’s gestation. (“He liked to watch his sitters in movement,” says the artist Celia Paul, who posed for him, in her memoir Self-Portrait, (Jonathan Cape).) At an exhibition in London, Julian Barnes’s eye was caught by Singer Sergeant’s portrait of Dr Samuel Pozzi, a figure in Belle-Époque Paris. The Man in the Red Coat (Vintage) tells the life story of this surgeon and philanderer with sympathy. If the characters seem like they have stepped out of Proust, that’s because they mostly have. As ever, the best accounts of real lives use the highest techniques of fiction.