In the 1970s, Rose Boyt was a teenager alone in “legendarily dangerous” New York. Acting as her father Lucian Freud’s emissary for an exhibition of his works, Boyt had a new Vivienne Westwood bondage dress but not enough money to pay for somewhere to stay. Andy Warhol was one of her unlikely rescuers. He took her to his regular haunt, Studio 54, and made a joke proposal of marriage. His presence is like a ghost on the book’s front cover: in a Polaroid photograph Boyt took of herself in the World Trade Center, he is visible on her finger. He had drawn the engagement ring and labelled it “AW”.

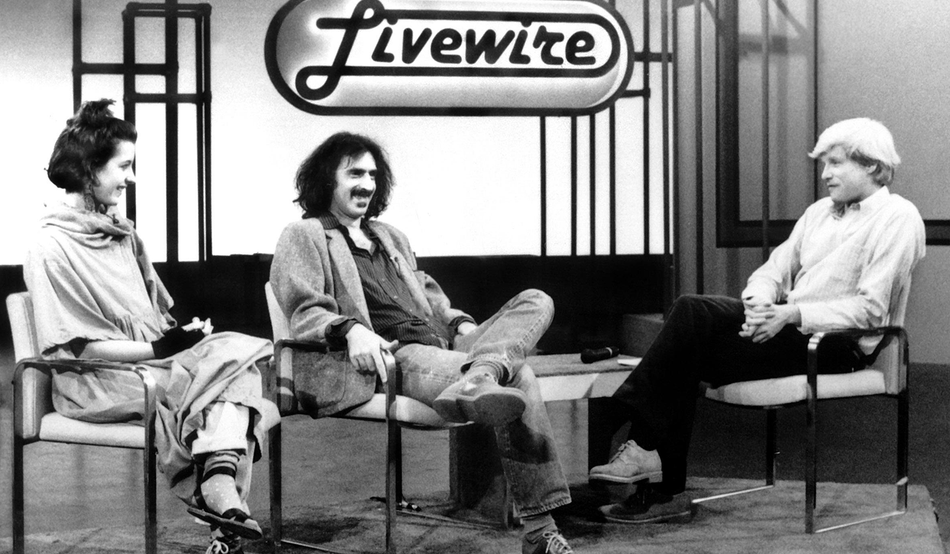

Warhol is an improbable hero for members of the daughters-of-famous-and-dissolute-fathers group, and he appears in the pages of two new memoirs, from Boyt and Moon Unit Zappa, whose reprobate dad was the musician Frank Zappa. For the younger Zappa, Warhol proved something of a momentary champion. In his posthumously published diaries, Warhol recorded a conversation he’d had with Frank. He praised Moon and, in response, Frank uttered the stomach-turning line, “Listen, she is my creation. I invented her… she’s nothing actually, I’m behind it.”

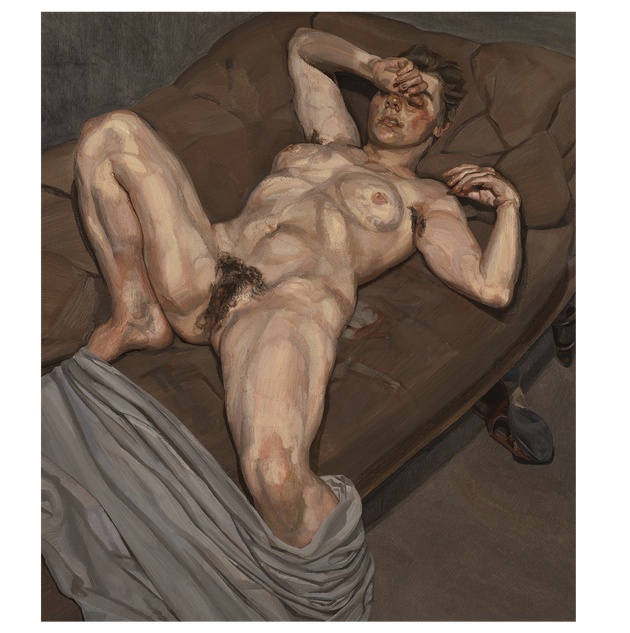

There’s one sense in which Frank’s words are true. Both Boyt and Zappa do exist as their father’s creations: Boyt sat for three paintings—the most famous gives name to her memoir, Naked Portrait—and Zappa appeared as a high-pitched parody of a Californian teenager on her father’s 1982 song “Valley Girl”. Their memoirs mark two attempts to interrogate a father’s art and two attempts to tackle the ghost of a father more broadly. What does it mean to grow up idolising a parent? To have scores of half-siblings? To appear in a father’s art—to be a part of what he created?

Rose, 1978–79 is a painting that dares you to be middle class enough to express shock. Boyt lies back on a bed, one arm bent so her hand is near her shoulder, the other shielding her eyes from the studio lights. One leg is covered with an artist’s dust sheet, the other bent up at the knee. The pose exposes everything: Boyt is naked (“nothing had been discussed, I just assumed”). Upon its completion, Freud—a grandchild of Sigmund Freud—wanted to call it The Artist’s Daughter, but was dissuaded by Boyt: “his title would make anybody think about incest.” Perhaps one of the most bleakly funny lines in the book comes when Boyt writes that her father “was not himself conscious of Freud’s theory about Oedipus”.

At the time it was painted, Rose was just 19. She posed for her father during the night and studied at London’s Central School of Art and Design during the day. Boyt describes the sittings as a kind of bizarre vaudeville act: Freud alternately reciting Shakespeare’s sonnets and the Earl of Rochester’s crude poem about Nell Gwyn, and then stabbing himself in the leg with his paintbrush if things were going wrong. There’s a remarkable lack of vulnerability in what Boyt remembers. She always left his Holland Park studio “elated” by their conversations. That might have been the effects of the drugs which Freud gave her to mitigate her lack of sleep: blue “Purple Hearts”, which he told her were “used by fighter pilots during the war to keep going on overnight missions”.

Freud painted Boyt at the end of her childhood; he made her a part of his artistic world—a product, a creation, a muse—and she was delighted to simply be in his orbit. After the painting was finished, she took the job of cleaning his studio, “feeling humble and picturesque in my bare feet with the mop and bucket”. It’s a picture of filial devotion that is not matched by the care Freud showed Boyt in her childhood. She was registered for a birth certificate without a surname; her mother, the artist Suzy Boyt, was too nervous to ask Freud for the privilege. On the day Rose was born, Freud appeared at the house where Suzy and her two children slept on the floor in the sitting room (Rose is the second-oldest of five children) holding two live lobsters, which Suzy had to boil in the nappy bucket. Suzy was allergic to shellfish.

Boyt doesn’t shirk from describing the difficulties of her childhood. Her mother was an art student, Freud her visiting teacher. Predictably, after their affair, Suzy was expelled while Freud was allowed to continue in his post. Suzy and her children bounced between drafty, litter-strewn Islington houses—always short of money, despite Freud’s growing riches—before they ended up on a leaky schooner circulating between ports in the Baltic. This twist in fortunes came via a German sea captain, Uwe, with whom Suzy had a relationship. Eventually, the family ended up in Trinidad, from where they had to be repatriated after Uwe sank the boat. It was a return to London life—and some stability—but not before the trip had done its damage. The infant Kai, Suzy’s fourth child, very nearly died after falling overboard, and Uwe made sexual advances on the seven-year-old Boyt.

Naked Portrait is like this. Film-worthy details, pictures of glamorous destitution and a healthy amount of name-dropping rub up against utter horror. (At one point, Boyt describes a conversation with Suzy about Uwe in which her mother reveals that “he had gone all the way with one of her own daughters.”) But, after her description of her childhood and her first sitting for Freud, Boyt changes tack: the book becomes a fragmentary commentary on a diary she kept in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Boyt sat for a portrait again in 1990. This time, she was fully clothed, in a navy blue sweater, with her hand cupping her face. But Naked Portrait isn’t a fairy tale; there is no catharsis in this sitting. What Boyt describes instead is a fraught relationship: a woman old enough to resist some of Freud’s power, but still sufficiently drawn in by his magnetism to put up with any number of humiliations. Freud enjoyed being open with his daughter, barraging her with “sex talk”. In her commentary on the diary, Boyt writes that she now thinks she should have put her “hands over [her] ears and screamed SHUT UP YOU SICK FUCK”.

The diary is a record of the competition Freud engendered: squabbles over inheriting furniture from the Freud grandparents, outsized feelings of shame and mortification when a sitter is dropped, extreme jealousy towards anyone—or thing—he might love. Freud is portrayed as a small deity. The many scions and branches of his family (he had 14 acknowledged children) are only happy when he grants them his favour.

Boyt claims her father is obsessed with beauty—his “valorisation of the appearance of people and objects”—but it seems a fit description for her entire circle: Boyt compares herself to her father’s many lovers (“the lovely half-starved women he desired”); relates her mother’s conviction that her own life would have been different if she had been “beautiful”; recounts Celia Paul—another of Freud’s lovers—growing upset over her appearance in one of his portraits. But there’s nothing superficial about this obsession. It’s a part of something larger, an awareness of Freud’s particular way of viewing the world, and a desire to be found worthy within these parameters.

Boyt’s diary reflects the rules of this Freud-centric universe, but there’s a delicate intimacy to it too. It’s a record not just of her sitting for her portrait but living amidst the mixed Freud clan—writing her novels (Sexual Intercourse in 1990 and Rose in 1992), helping care for children and attending endless, near-daily meetings with her psychotherapist. At times, the descriptions of London Review of Books parties and of writing articles for Tatler begin to grate in their repetition, but Boyt’s piercing lack of self-satisfaction prevents it from becoming more cloying.

Boyt is an incredibly accomplished writer. The two novels she describes working on in the diary took elements of her real life—a mother’s affair with a sea captain, a daughter desperate for her father’s approval—and transformed them into fiction. There’s a similar undertaking in the memoir: an ability to make grim autobiography compellingly readable. Moon Unit Zappa unfortunately does not have the same gift.

There are some broad-brush similarities between Boyt’s and Zappa’s stories: both are born into dysfunctional families, both put their creative father on a pedestal, both have (to put it mildly, in Zappa’s case) complicated relationships with their mothers. There are a scattering of more amusingly idiosyncratic similarities too: both write of their love of Mason Pearson hairbrushes and Vivienne Westwood clothes (at one point, Zappa visits Westwood’s shop in London, perhaps at the same time Boyt was working there).

Zappa was a cultural legend from her birth, with her unusual name causing shock waves in the United States. She was born in 1967—or as she puts it, in a particularly strained image, “the same year Elvis surrenders his pelvis to marriage during the sexual revolution”. Her childhood was one of a Californian hippie, all New Age spirits and calling parents by their first names. But things quickly got darker. Zappa’s mother, Gail, was only 20 when she met and married Frank; in the course of three more children and Frank’s rock career, their relationship soured, owing to his endless affairs with groupies. Gail took out her frustrations on her eldest daughter, often leaving her in a state of semi-neglect.

Zappa writes much of the book from the perspective of her childhood (by chapter 15, we are only at age 11). She describes everything in a studiedly naive way (“my daddy thinks I am beautiful”), before adopting a therapised lexicon: “what I don’t yet know is shunning and estrangement are a part of my family’s vocabulary.”

It’s a conceit that quickly becomes tiresome—making the book feel less like a memoir and more like a psychology case study—but it makes sense by the later chapters. After her traumatic childhood, Zappa found fame as a teenager as the voice on “Valley Girl”. Her external success—appearances on the radio and late-night television—is matched in equal measure by her parents’ displeasure: Frank angry that it took his daughter improvising for him to get his first megahit, Gail cross that her daughter is receiving more attention than her. In her adult years, Zappa attempts to undo the damage her parents wrought on her by devoting herself to a series of guides. She is ready to dedicate herself to anyone who places themselves above her, from gurus (“I put photos… up everywhere in my house to remind me that everything flows from her to me”) to acting coaches. It makes for a depressing read: a study of a woman with a non-existent sense of self, ready to submit to anyone who promises her care.

Sadly, Zappa’s best writing is about a time of extreme trauma, when her daughter, Mathilde, was hospitalised and very nearly died. It makes for a neat inversion of Zappa’s own childhood—a story of love, as opposed to the lack of it. But, even late into her life, Zappa still can’t avoid the pull of her parents. Reading the book—and learning how Zappa gave up her house for her parents and agreed to sign away her rights to Frank’s wealth in order to ease her mother’s financial difficulties—I felt like shaking her, to make her see how under their spell she is. Why, oh why, did she keep letting herself be exploited? It seems to be a question with no answer, and the end of the book leaves little hope. Ostensibly describing her own “healing”, she recalls a time when a friend recommended a therapist to her: “I talk to her. She says that if we meet once a week, starting today, she can reparent me in three years. I think, FUCK THAT, I’ll get three therapists and do it in one year.”

It’s hard not to scoff. Is this not the same thing: latching onto authority figures and then elevating them?

Reading Naked Portrait and Earth to Moon together, I began to question why they were written. Why would anyone want to set out all their family difficulties on the page and make themselves so vulnerable? Is it about the authority of print, conferring a kind of validation from readers about how bad a person or a situation was? Is it exoneration through honesty?

Despite what people might assume—eager to hear of Freud’s failings as a father, about the painting of his daughter’s open legs—Naked Portrait was not, I think, written to punish Freud. It’s open about his failings, but amounts to far more than just a litany of his flaws. Boyt takes her memories and diary entries and alchemises them into something else: a book about creativity and its fraught place in family relationships.

Zappa can’t quite do this. Her memoir is more earthbound, stuck in settling scores about parental failings and sibling rivalries.

Yet both books end with scenes of forgiveness: words scribbled on a pad for Boyt, a text message for Zappa. Perhaps this is what the authors were always writing towards: a truce, with family members and the past.