In 1981, the week I was born, Posy Simmonds’s Guardian comic strip was titled “Visiting time in a maternity ward”. A mother and her newborn daughter are surrounded by well-wishers. “Shame you didn’t have a boy,” commiserates one. “Ah well… better luck next time… Aaah! But she’s gorgeous!” coos another. Up and down the ward, the chorus is the same: “Still there’s plenty of time isn’t there? P’raps you’ll have a boy next time”. Meanwhile, a young woman discreetly slides an “It’s a Girl!” card onto the bedside table, the poem on the front of which is shown in detail in the final box of the strip, complete with her weary side-eye:

Here’s a special birthday greeting

to tell you of our joy….

You’re ev’ry bit as wanted dear,

As if you’d been a BOY!

We mustn’t make distinctions now…

GIRLS are just as good and true

You march alongside boys thru Life

And fight the battles too!

Your role is just as vital

In love and peace and war…

….Tho’ BOYS are officers in Life’s Guards

And GIRLS the Catering Corps!

Everyone was convinced that my mother was having a boy, so the strip was especially apt; she snipped it out and kept it. As a child, I liked to look at it, as I did all of Simmonds’s cartoons. Initially, I understood nothing of the subtext, but as I grew older, Simmonds’s virtuosity began to dawn on me. So too her feminism.

When I went to interview her in May, I dug out the clipping and tucked it into my notebook. In January, Simmonds was awarded the Grand Prix at France’s Angoulême International Comics Festival, the world’s most prestigious prize for lifetime achievement in comics. This is impressive in and of itself, but all the more so given that the 78-year-old is the first Brit and only the fourth woman to win in the prize’s 50-year history.

Alas, she didn’t attend the festival itself because she was stuck at home in London after dental work, which she’d literally just had done when her French editor called with the news. “The BBC rang me to do a radio interview, and I was saying, ‘I’m terribly sorry, but I probably won’t make much sense.’”

With splendid serendipity, the award coincided with a retrospective of her work at the Pompidou Centre, covering all aspects of her career, from the portfolio with which she applied to art school in the early 1960s, through her years as a newspaper cartoonist, her books for children and, most recently, those for adult readers, the latest of which, Cassandra Darke, was published in 2018.

The first thing she tells me about the exhibition, though, is that it was disrupted by the bedbug infestation that was sweeping Paris. The parasites colonised the carpets in the Pompidou Library, which meant the show was briefly shut down while exterminators were called in. Simmonds is grinning while she tells me this. Behind her warm and elegantly spoken exterior is a deliciously naughty sense of humour. She’s also an obscenely talented mimic: the only castaway on Desert Island Discs to have reduced Kirsty Young to hysterics, with her impersonation of a chicken; as well as indulging in a cacophony of fart noises with Clive James during her appearance on his Talking in the Library television series. (Both are well worth googling!)

In 2019, London’s House of Illustration held a fine, albeit long overdue first retrospective of her work, but the Paris exhibition was even larger. Its setting was fitting as the French capital has had a special place in Simmonds’s heart ever since she studied at the Sorbonne as a 17-year-old: the most “wonderful” experience, she tells me. It was her first time living abroad and her first taste of independence away from either home (she grew up in the small village of Cookham in Berkshire) or boarding school. “There was nobody to tell me what to do or what time to be anywhere. At school you’re always rushing somewhere. I just walked and walked. I walked everywhere, and I went to the cinema three times a week, it was so cheap.”

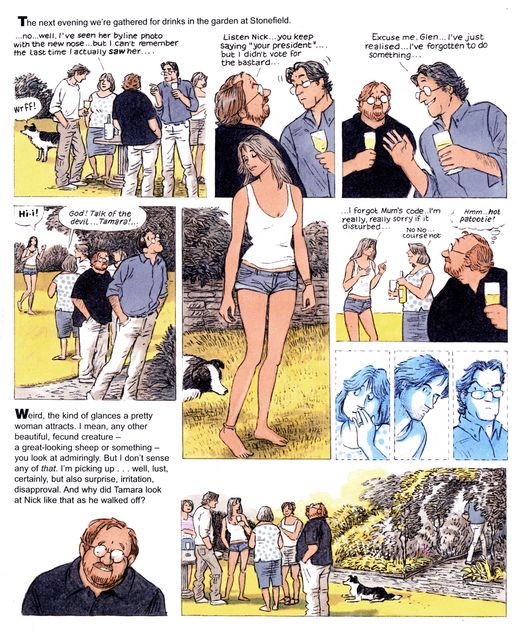

France, of course, has also long been ahead of the UK and the US when it comes to taking its cartoonists and graphic novelists seriously as artists, and Simmonds has a robust following there. Here in the UK, we like to applaud the Englishness of her work. Praising her graphic novel Tamara Drewe (2007), the Sunday Times hailed her “a true child of Hogarth, her accomplished cartoons a merciless commentary on the way we live now”, and she’s known for skewering the white middle classes. While true, this emphasis can inadvertently sideline her other talents, namely the trailblazing stylistic innovations that her transformation from cartoonist to graphic novelist has entailed, and the uniqueness of her style of hybrid storytelling. Her trademark combination of words and pictures is so heavy on the text that some purists have argued the description “illustrated novel” better serves Gemma Bovery (1999), Tamara Drewe and Cassandra Darke. This wrangling over terms is not new to her. “What is it?” she remembers Tom Maschler, her first editor at Jonathan Cape, asking when she presented him with True Love: “A cartoon story?”

Published in 1981, and now considered by many to be the UK’s first graphic novel, True Love was an ingenious parody of the romance comics that fed stories of “happily ever after” to impressionable young women. Its feminism is evident but not sanctimonious, and, as in all her work, Simmonds never sacrifices entertainment for hectoring. I’m reminded of one of my favourites of her Guardian strips from later in the same decade, “The world turned upside down” (1987). “Hello Ballsy,” shouts a woman builder to a man as he tries to furtively slope past, shoulders hunched. He’s on his way to the pub, but not for a swift one with his mates. He’s there to deliver a document to his female boss. “Ooh! This nice young gentleman works for you, Erica?” ogles one woman. “Wouldn’t kick that out of bed, would you, Mandy?” leers another. Today, of course, it scans like a blooper reel from Naomi Alderman’s Women’s Prize-winning novel The Power, but back then this was radical stuff.

‘Perhaps I was the last generation where we were expected to be the wives of doctors or whatever, rather than being them ourselves.’

“There was lots of everyday sexism around,” Simmonds confirms when I ask her about the social climate that fuelled this and her other Guardian cartoons from the 1970s and 1980s. But it was also simply the world she’d grown up in. Before she went to art college, she worked briefly at Harrods, where she remembers being paid “much less” than her male colleagues of the same age. “Perhaps I was the last generation where we were expected to be the wives of doctors or whatever, rather than being them ourselves. I mean, they were keen that we went to school, and that we studied, and even went to university. But there was this assumption that then you’d get married and give up your job.”

Thankfully, though, things were a little different at the Guardian, where she began working in the early 1970s, a few years after graduating from London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts (now Central Saint Martins). She started out there illustrating occasional stories towards the beginning of the decade and then, in 1977, was given a regular weekly strip on the women’s page. “We’d get letters asking, ‘Why are you talking about women’s innards all the time?’” she laughs. But, she assures me, it wasn’t a case of being shunted off into the corner, away from the more important reporting that the men were doing. “No, it was very new, very exciting. There were really good people there, like Jill Tweedie and Polly Toynbee. You felt you were part of a team.”

Her first regular strip, “The Silent Three of St Botolph’s: 20 Years On”, riffed on the girls’ adventure stories that were popular in the comics that Simmonds read as a child. The “silent three” were Trish Wright, Wendy Weber and Jo Heep—now wives and mothers—who, “when DUTY calls,” readjourn the secret society that they formed as schoolgirls. Over time, the characters developed, and the Weber family soon took centre stage. Wendy was a nurse, George, her husband, a lecturer at a poly, and they had six children, from toddler to teenager, thus allowing for the full gamut of parenting highs and lows. Whether on holiday in Tresoddit, the fictional Cornish hamlet with which Simmonds’s readers soon became intimately acquainted, or simply arguing over the purchase of a new kitchen blind, these “well-meaning woolly liberals”, as she once described them, captured readers’ hearts.

“I was very fond of them,” she says, adding that poor George in particular courted a lot of attention. “I used to get letters from academics saying, ‘Why does he talk such balls?’” Alas, the advent of the Thatcher years sounded their death knell: “Things got a bit carnivorous, and they were definitely herbivores. But I also wanted to do something else.”

Herein lies the secret to Simmonds’s impressively long and multifarious career. Change doesn’t seem to faze her. When, in the mid 1990s, the Guardian offered her a serial in 100 episodes, published Monday through Saturday, with each ending on a cliffhanger, she was excited by “challenge”, both of the extended scope of the storytelling this would entail and the new format she was given to work with—a vertical, rather than horizontal, layout, three columns wide. The result was her masterly take on Flaubert’s 19th-century classic: “The Late Gemma Bovery: A Tale of Adultery and Soft Furnishings Narrated by Raymond Joubert” (subsequently published as the graphic novel Gemma Bovery). Having alighted on the idea for the story, she re-read the original just the once, then put it away and set to work.

When the first episode was published, she had about 25 more ready to go, after which it became a race against time. “It was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. I was writing something that was hatching, which made it quite exciting but also terrifying. You have to make lightning-quick decisions. At the end, I needed a holiday!”

We’re sitting in her workroom in the London flat that she and her husband, the graphic designer Richard Hollis, downsized to during the pandemic. It’s a light-filled room with large windows; the whole end wall is taken up with her drawing desk. Above this is a large gilt-edged mirror, which she uses to capture facial expressions, surrounded by shelves containing a mixture of notebooks, novels and non-fiction titles, and some large cardboard boxes into which she’s recently been filing old material.

She generously gives me a tour through her Gemma Bovery archive. First up are the sketchbooks with which every project begins. As she flicks through them, I watch the characters slowly emerging into their final physical forms. She shows me a page full of sketches of Princess Diana’s head, her eyes looking upwards from under her fringe, then the look transferred to what I recognise as Gemma’s emerging profile. On another page, her heroine is trussed up in sexy lingerie. “You have to visualise it properly,” Simmonds says, explaining that whether a certain detail makes it into the final work or not, it’s all grist for the mill. “I realise now, it’s sort of like a film’s pre-production, because you’ve got to make so many decisions before you start about what people look like, what the interior of their house is like…”

‘My best present ever was when I was about eight, and my father gave me an elephant-sized ream of paper.’

After Paris, she originally applied to the Central School to study painting, but during the pre-diploma course—when students tried their hands at all specialisms—she became aware that graphics was much more her thing. “I’d always liked drawing images and writing,” she clarifies, telling me about the comic books that she created as a child. “My best present ever was when I was about eight, and my father gave me an elephant-sized ream of paper.” (For the uninitiated, like me, that’s 500 sheets.) “There was a tallboy in the hall which had a very big bottom drawer. And I remember on Christmas Day him saying, ‘Come and look at the tallboy,’ and he opened the drawer—which was heavy—and said, ‘This is for you.’ It was just wonderful. And it lasted all my childhood.”

In the pre-electronic era of the 1960s, graphics was very much a typographic course (though she recalls “bending” a few projects so as “to sneak in some illustration”). And part of this was learning to draw three or four different typefaces by hand. A lost art today, but extremely useful when working on the page layouts for Gemma Bovery (and later Tamara Drewe, which also first appeared in serial form in the Guardian), since she could anticipate with accuracy how much room each bit of text would need.

Setting the text is very much the easy part, however. Writing it takes a lot longer. The words are the part of the storytelling process that she says comes least naturally. Not that I’d guess this, such is the fluent symbiosis of the finished work.

As our time together draws to a close, I finally make my gushing confession and produce the sepia-toned clipping from my birth. “I’d forgotten this one,” she says, taking it from me, chuckling to herself as she reads the poem out loud. Her performance—which, despite the lack of rehearsal and the passage of over four decades, is word perfect and gets every stress and emphasis spot-on—is the icing on the cake. Brava for the Catering Corps!