One hundred and seventy-five years ago, William Ewart MP presented two petitions from the inhabitants of Birmingham to the House of Commons,

complaining of the want of public libraries. The hon. Gentleman then proceeded to move the resolution of which he had given notice. He said, for several years they had introduced into this country various enlargements of our formerly exclusive system, in reference to the arts, after the example of foreign countries… but there was one instrument of public improvement common to foreign countries which did not exist in this… the institution of public libraries freely accessible to the people.

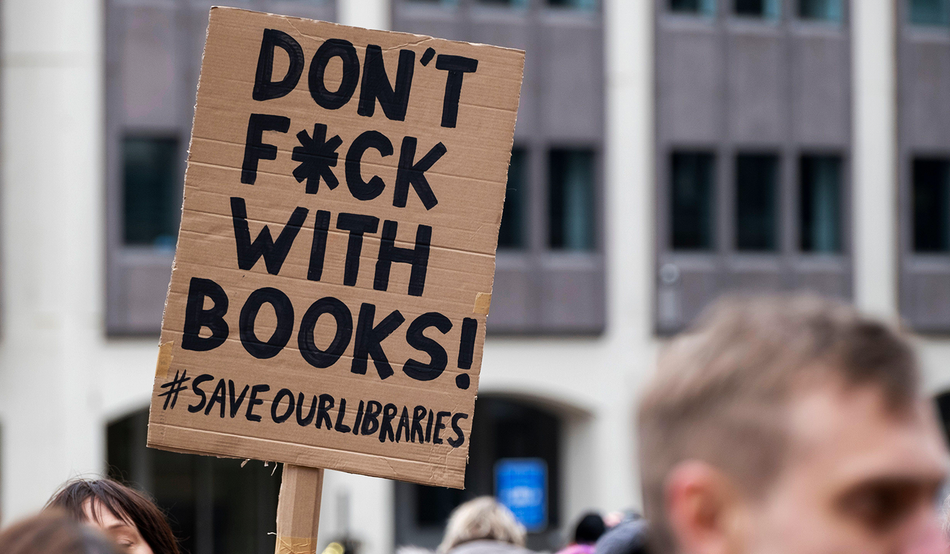

Ewart’s efforts resulted in the 1850 Public Libraries Act, paving the way for the system that we have in place today. It is a tragic irony, therefore, that the embattled City of Birmingham is currently a ground zero for the public library system in this country, with one of the options under consideration being the closure of 25 of the existing 35 branch libraries in the city, the remainder slated to become joint “library and neighbourhood advice service hubs”, with a fifth of library staff set to be made redundant.

Libraries, of course, are not alone in being targeted. Virtually all aspects of the council’s adult social care directorate (under which libraries operate) will be affected by budget cuts of more than £50m across the next two years. At this scale, the cuts would be devastating for the people of Birmingham, depriving generations of opportunities for learning, inspiration and the expansion of intellectual and cultural horizons, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in society, adversely affecting their life chances long into the future.

To rectify this for Birmingham—and for libraries across the country—we urgently need the incoming government to place a long overdue focus on libraries, and to develop a supporting national strategy, bringing together all of the library ecosystem, including public, school, national, university and specialist libraries. Libraries are a key part of the infrastructure of democracy: in Ukraine, libraries are being deliberately attacked by Russian forces—here we are effectively attacking our own provision through severe cuts to funding.

In many ways, libraries today are extremely successful. Trusted by communities, they are also places of innovation, deeply involved in the provision of digital literacy and skills, as well as in digitising their collections and in managing and preserving digital information. They are among the only genuinely open public facilities that remain free and are not transactional in their delivery of a service. Young and old can mingle safely together, whether in the pursuit of self-improvement, education support, access to information about health or benefits, knowledge to support business development, or just the enjoyment of reading, culture and learning. Libraries help combat loneliness, encourage empathy and enable people to engage with a modern democracy.

More than a decade of austerity has, however, ravaged the public library sector. I am reminded of Alexei Sayle’s remark: “Austerity is the belief that the 2008 global financial crisis was caused by there being too many public libraries in Wolverhampton.” More than 800 public libraries directly run by councils have closed since 2010. Across the country libraries have sought creative challenges to the situation, co-locating services inside larger facilities. In Newcastle, where the Citizens Advice Bureau is now found inside the Central Library, opening hours across the service have halved, and large parts of the physical book stock have been removed to create spaces that can be hired out.

The current crisis is being assiduously tracked by the website Public Library News, which is also mapping a longer trend: the de-professionalisation of libraries. More than 600 of them have been turned into what are euphemistically called “community” libraries, that is to say run by volunteers. This is not to denigrate the value of the time and expertise generously given by people across the country (the Bodleian, where I am director, benefits enormously from its volunteers), but such efforts mask the reduction of professional expertise across the sector, where the number of qualified librarians has shrunk by more than 12,000 since 2010.

At the same time as the public library system is facing an existential funding crisis, the British Library—our national library—suffered a savage cyberattack in October 2023, rendering its operations severely limited ever since. In the past few months services have slowly been reintroduced, but these have been limited in scope, despite the strenuous efforts of the library’s staff.

At the time of writing, the British Library is expecting to have to fund the multi-million pound cost of the rebuild of its digital estate from its own budget. This will put further pressure on the library, despite the continued disruption of services to users of its physical buildings, and the equally serious impact of cutting off the supply of national digital collections to other libraries, including the five legal deposit libraries across the UK (which, in the spirit of full disclosure, include the Bodleian).

I have argued elsewhere that the cost of rebuilding the digital infrastructure of the British Library should be borne by the nation. Budget cuts suffered by the library over many years have undoubtedly led to the gaps in its digital protection that were exploited by cyber-criminals. The nation effectively self-insures its national library, and our insurance policy must urgently be invoked.

The idea of a public library is not a new one. In the 17th century, Gabriel Naudé, in his Advice on Establishing a Library, commented that Europe only had three libraries (in Oxford, Rome and Milan) where the public “could freely enter and without difficulty”, though his idea of the “public” was far more restrictive than ours today.

From the late Middle Ages, parish libraries had been established across Britain that gave people limited access to knowledge. At Wimborne Minster in Dorset, for example, the churchwarden’s accounts record gifts of books from 1475 onwards. In 1686, William Stone, a local clergyman, gave 90 volumes for the use of “gentlemen shopkeepers and the better sort of inhabitants in and about the town”—far from equal access. Those books are still accessible today.

In the 18th century the drive towards growing literacy and self-improvement created a dramatic expansion in access to knowledge. Changes in the publishing industry supported this, but access to books, newspapers and information in print was made possible in shared form through subscription libraries aimed mostly at the expanding middle classes. There were libraries, however, for working class readers that did not require payment to become a member and access books—by 1934 miners and their families in Wales had access to over 100 well-stocked libraries.

It was this milieu of the demand for self-improvement through access to knowledge that lay behind the House of Commons Select Committee Report on Public Libraries and the 1850 Act which followed it.

The report makes for poignant reading in 2024. Comparing Britain then unfavourably with European countries, it called for action: “Your committee feel convinced that the people of a country like our own—bounding in capital, in energy, and in honest desire not only to initiate, but to imitate whatsoever is good and useful—will not long linger behind the people of other countries in the acquisition of such valuable institutions as freely accessible Public Libraries.” Such optimism was borne of the moment of opportunity in Britain, and the sense that broadening access to education through access to knowledge would help drive the nation forward.

The Select Committee report resulted in legislation that would make it possible to improve people’s free access to knowledge. The 1850 Act (and further legislation in 1853 which applied to Scotland and Ireland), allowed—but did not compel—municipal boroughs to establish free public libraries through levying local taxation. Only in 1964, after the establishment of the welfare state, was the requirement put into law.

These reports, and the strategy that took hold 20 years ago, have been simultaneously overtaken and undermined by years of austerity

According to the 1964 Public Libraries and Museums Act, “It shall be the duty of every library authority to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons desiring to make use thereof.” Part of the problem now is that the act does not define clearly enough what “comprehensive and efficient” means, and therefore lacks teeth to enforce it. Local authorities can fudge it.

The early years of the 21st century were marked by a sense of renewed energy around public libraries with the publication of two key reports. One, spearheaded by the minister for the arts Tessa Blackstone, looked ahead to how public library services should develop, with the introduction of large-scale provision of computers in public libraries through a major initiative called “The People’s Network”. This paved the way for the expansion of digital provision of books and information, bringing with it the need to offer digital skills developments in libraries.

The report is permeated by the sense of opportunity afforded by new technology, but also the challenge faced by libraries in responding to it. What is also striking was the acceptance that the deepened devolution of responsibilities for public libraries to local authorities would lead to uneven innovation, and fragmentation of service development, making it difficult to spread good practice across the sector.

A different emphasis was placed by the other report on libraries from this period, the House of Commons Select Committee Report on Public Libraries (2005), chaired by Gerald Kaufman MP.

Public libraries… together with their staff, are a trusted civic amenity—highly valued safe public spaces and storehouses of advice, information and knowledge—without which the citizens of Britain would be very much the poorer.

Looking through this report now seems like a journey back to a distant age, rather than just 20 years ago. Its focus was on literacy, reading and books (“the bedrock” of library services), warning that “libraries must not be over-loaded with objectives or expectations that strain their resources or inhibit their fulfilment of their core functions.”

The role of “superintendence”, which was an integral component of the 1964 act, was identified in this report as being shirked through the increased delegation of powers from central government to local authorities. Where was the national overview, with the focus on standards, equity of provision across the nation, and on the development of the sector as a whole?

These reports, and the strategy that took hold 20 years ago, have been simultaneously overtaken and undermined by the years of austerity. The effective transfer of responsibility away from central government (namely the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, or DCMS) to local councils had taken place before 2010, but the impact of the cuts to local government spending that ensued meant that libraries became easy targets for reducing costs.

During the last quarter of the 20th century Birmingham became one of Europe’s flagship library services, able to balance a focus on the local communities in the city as well as a strong central provision, on a “hub and spoke” model. A new Central Library was built in 1974 and the following decade saw a growth in both collections and services. By the start of the new millennium, it was generally agreed that a new building was needed to replace the Central Library, and the Library of Birmingham was conceived in the early years of the new century. The new building was triumphantly opened in 2013 at a cost of almost £200m. Strikingly designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo, it incorporated a variety of spaces beyond straightforward library collections and study and service points, and from the start has had consistently high visitor numbers.

Birmingham Council’s financial position, however, almost immediately began to tarnish the shine of the new library. Opening hours were restricted and more than 100 staff were axed, including many of those responsible for historic collections. These funding cuts have worsened in recent years, coming to a head 175 years since the citizens of Birmingham made their plea for a free public library.

A consultation is currently underway to reorganise the branch libraries into “community living rooms”, although which of the 35 existing libraries will undergo this change is not known. The remainder, it seems, will be considered for “community led provision and co-location in community venues”. Perhaps another 20 libraries will be added to the list maintained by Public Library News.

One of the great elements of success of public libraries is their embeddedness within neighbourhoods. Branch libraries know their communities extremely well, and over the years they have extended the range of services beyond providing access to books, journals, the internet and other forms of knowledge. Exhibition spaces, as well as rooms for community groups to gather inexpensively and in a “neutral” location, are highly valued.

Some of this extension has been out of necessity, as social care budgets have been put under pressure. Libraries and librarians have picked up some of the slack, but this in turn has put pressure on their own core activities. The second blow for many public library services is that they were already dealing with the most underprivileged sectors of society, in areas of great poverty and with ageing populations. While there was such a high level of need, the role of the library in the community meant that their services, and staff employed to deliver them, were becoming increasingly stretched.

In 2018 Philip Alston, United Nations special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, published a powerful condemnation of the condition of British society. “Digital assistance has been outsourced to public libraries and civil society organisations. Public libraries are on the front line of helping the digitally illiterate who wish to claim their right to Universal Credit.” In the meantime the bookstock, what the Kaufman report regarded as the bedrock of the public library service, has continued to dwindle, with less and less money spent on books each year.

Libraries have always been interconnected. In the Renaissance the first union catalogues—which identify resources spread across multiple locations—were published. In 1710, the Copyright Act of Queen Anne (entitled “For the Encouragement of Learning”) established the principle of legal deposit, where British publishers would provide free copies of books to key libraries in England, Scotland and Ireland. This system is still in force today, connecting the British Library, the Bodleian in Oxford, the University Library in Cambridge and the Library of Trinity College Dublin, as well as the National Libraries of Scotland and Wales, spreading the responsibility for both preservation and access to deep research collections, materials that will be used over and over again for centuries.

The law was extended in 2013 to cover digital publications, vastly expanding and updating the range of knowledge accessible to the public through those libraries. The hack on the British Library therefore has, however, had a magnified effect on the whole library system, and more importantly to its users, whether they are entrepreneurs, students, researchers, creatives or family historians.

We now need a national strategy for libraries across the sector, not confined to public libraries, but uniting all the services that are in receipt, in one way or another, of public funding: national libraries as well as university, NHS, school and public libraries.

In 2022, the Conservative government commissioned the peer Elizabeth Sanderson to develop a new public libraries strategy. Her report, which landed in the early weeks of this year, has been welcomed from sector bodies, who really felt that she was listening to them. Sadly, its remit did not look beyond public libraries, although it did recognise the need for the closer involvement of the British Library.

Libraries contribute to so many aspects of our public life—they are at the heart of the knowledge economy

There is a lot in the report that is commendable, such as recommendations to expand the take-up of library services. She also makes the critical point that ministerial responsibility for libraries has been buried for many years within the brief for Arts and Heritage at DCMS. She suggests adding “libraries” to the title. I don’t think this goes far enough.

Libraries contribute to so many aspects of our public life—they are at the heart of the knowledge economy, education, culture and the creative industries, heritage as well as social care—that we need a distinct minister for libraries. The responsibility for funding libraries is highly distributed across government. For national libraries, such as the British Library, funding comes through DCMS. For public libraries, this is the responsibility of the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. For school and university libraries, it lies with the Department for Education.

A new ministerial brief could help highlight the contribution made by libraries across different areas of the government’s agenda, and help define new joined-up strategic opportunities and directions. In order to do this effectively, it should also redress the balance of power and the allocation of funding between central and local government: it is vital that localities can be in control of their own destiny. However, without central strategy, standards and directed strategic funding, we will not get out of the cycle of decline and uneven provision, especially for public libraries. Perhaps the responsibility for libraries would make a more compelling fit with the Department of Education or local government rather than with Culture, Media and Sport?

There needs to be a clear acceptance that the “superintendence” role implicit in the 1964 act needs to be taken seriously as a governmental responsibility, so that standards can be set, improvement supported and the sector can be developed in a joined-up fashion to help deliver broad governmental priorities.

The Sanderson report shies away from the crunch issue: sustainable revenue funding. Her report has much to say about encouraging more volunteering, and the role of other charitable bodies such as the National Literacy Trust in delivering library services. But the report is silent on the level of funding available to support the work of public libraries.

The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy’s latest annual library survey reported that funding between 2021 and 2022 fell 17 per cent from the previous year. The announcement of the third round of the Libraries Improvement Fund is extremely positive, with 43 library services receiving a share of £10.5m funding. Project funding of this kind is to be applauded, but it cannot replace sustained funding that allows services that take many years to develop and to continue.

The 1960s, when the requirement for free public libraries was put into law, were an exciting time for Britain. The ravages of the war and postwar rationing were fading fast, and a new sense of possibility abounded. Could Britain today regain such a sense of progressive optimism?

After the shocks of the 2008 financial crisis, the long years of austerity that followed, the impact of Covid and the grotesque political and social turbulence under the last five prime ministers, change seems not just necessary, but feasible. Just as 1964 saw the dynamism in the world of libraries as infrastructure for public education and access to culture, so too could a rejuvenated library system in the UK contribute to social, cultural and economic recovery, encouraging not just greater access to knowledge, but greater engagement with inspiration, creativity, community, citizenship and entrepreneurialism.

We need greater self-confidence in our people, citizens who can identify misinformation when it is fired at them, who are better equipped to engage with the democratic process, who have a sense of empathy for others in an increasingly polarised world, who can engage with ideas for longer than it takes to watch a TikTok. Writer Ali Smith spoke in Oxford earlier this year of her feelings about the current wave of cuts to public libraries: “To be deprived of these resources is to be deprived of the open availability of—the democracy of—reading; of a ready source of centuries of imagination, information, knowledge; and of the very notion that all of these things are our communal rights, never mind the open right-of-way they provide in a life…” In this election just gone, none of the manifestos of the major parties discussed libraries with anything more than a passing comment—a truly appalling omission.

The good news is that this generation of young people is rediscovering the library as a place of quiet, of accessible resources and as a source of community: somewhere that is “authentic and real”. All we need now is for our political leadership to catch up with them.