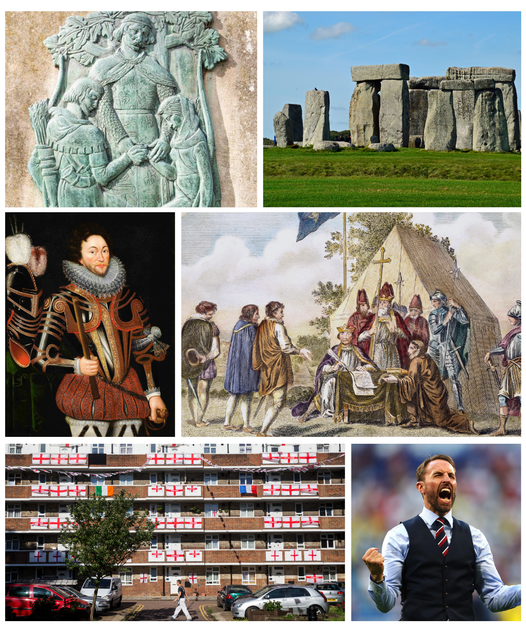

It all starts in Runnymede. Or at least Tom Baldwin and Marc Stears’s England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country starts in Runnymede—though many people would have us believe that a lot more began there too. The circumscription of the powers of kings, for instance. The protection of the God-given rights of the people. Democracy. Liberty. Even England itself.

For Runnymede—a corner of Surrey that’s now enclosed by the River Thames and the six-lane M25—was, of course, the place from where Magna Carta, the Great Charter, emerged in mid-June 1215. On its own terms, this was a significant agreement that sought to spare the country from an immediate, full-blown civil war. A group of rebel barons, unhappy at King John’s rampant unilateralism—particularly when it came to the raising of taxes—had already seized control of London. The meeting at Runnymede, between monarch and monied classes, was meant to resolve these tensions. After several days of discussion, a final list of regal concessions—the charter itself—was drawn up, including such humdingers as: “All fish-weirs shall be removed from the Thames, the Medway, and throughout the whole of England, except on the sea coast.”

Magna Carta was not mythologised immediately. How could it have been? Although King John’s placations were enough to resecure the barons’ oaths of homage that June, they did not secure a lasting peace. Only a few months later, John sought papal permission to rescind the charter—and civil war did break out. Then, in subsequent years, including 1225 and 1297, Magna Carta was reissued by other kings in need, and often diluted in the process. Runnymede became more water than watershed.

No, as Baldwin and Stears make clear in the deft opening chapter of their book, the mythologisation of Magna Carta has happened sporadically over centuries. It is true that some of its clauses are historically significant: four of the original 63 clauses are on the statute books today, including the famous pledge that “No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land.” But it is also true that Magna Carta has become something more than the sum of its provisions: in a large international poll conducted by Ipsos MORI on the occasion of the charter’s 800th anniversary in 2015, over a fifth of British respondents who were “aware” of its existence reckoned that it had “helped to guarantee” trial by jury—when it did no such thing. Much the same could be said of freedom of speech, freedom of religion and many other basic human rights. If you believe that Magna Carta helped to guarantee those too, then British history has a few lessons for you.

The fact that the notion—and it is mostly a notion—of Magna Carta still resonates is at least partly due to its usurpation by political actors. It was seized upon by the proponents of the Glorious Revolution in the late 17th century, who wanted historic underpinnings for their new Bill of Rights. It was raised by American-English colonists in their rebellion against the motherland in the 18th century. And, of course, it was brandished during the Brexit campaign as the ur-example of Britain’s—England’s—total specialness. To quote Nigel Farage—who else?—tweeting nine years ago, “#MagnaCarta is something we should be immensely proud of.”

Of course, Magna Carta was brandished during the Brexit campaign as the ur-example of Britain’s—England’s—total specialness

As its subtitle suggests, Baldwin and Stears’s book deals with seven stories that English people have told themselves (or had told to them) over time—not just about Magna Carta, but also about the achievements of William Wilberforce, the “rivers of blood” that would result from immigration, and more. It appears to be a good moment to be in the thinking-about-England business. Caroline Lucas’s Another England: How to Reclaim Our National Story has also been published recently, following Andy Burnham and Steve Rotherham’s political prospectus for the north of the country (see review here). There are new novels about how modern England rewires the minds of its young men (see here). There are books about English filmmakers (here) and architects (here). And just wait for all the printed words that will be expended on the English men’s football team during this summer’s Euro 2024 tournament.

Perhaps the heightened interest is because this is the year of a general election—now just weeks away—in which England will play an outsized role. This is not to knock the other home nations of the United Kingdom—Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland—nor is it to make a claim of English exceptionalism. It’s merely a statement of psephological fact. In the last general election, in 2019, England accounted for almost 27m of the 32m votes cast, or about 84 per cent. It returned 533 of the 650 seats on offer, or 82 per cent. Win in England, and you tend to win overall—which has basically been the Conservatives’ strategy over the past decade, if not for longer. The Tories have secured the most English seats in 21 of the 28 general elections since 1918.

And it’s not only general elections. In 2016, famously, England voted to leave the European Union by 53.4 per cent to 46.6 per cent (or by even more if you exclude London), which was greater even than Wales’s 52.5–47.5 split—and worlds apart from the remain votes in Northern Ireland and Scotland. But, of course, it was the sheer weight of one nation’s votes, all 13m of them, that carried the day. What England wants, England gets.

This may, in turn, help to explain why much of the recent thinking about England has been done by people on the political left; they have lost more from the nation’s dominance, but also, potentially, have more to gain. Baldwin, one of the mythbusters, is a former Labour party communications chief and worked on both the Ed Miliband and People’s Vote campaigns. Stears, the other, is a political academic who also advised Miliband, though he’s surely best known for being my tutor at university (what a pleasure it is to mark his homework for a change). Meanwhile, Lucas, the author of Another England, is one of the most exemplary politicians of the 21st century—for many, the face of the Greens, which she has led on two occasions, and is still its only ever MP, though she is standing down from her Brighton Pavilion seat in July’s general election.

Lucas’s book also seeks to bust a number of the myths that have accumulated around England, though it does so in a different way. Baldwin and Stears’s England is more an act of concerted analysis, presenting a myth (that Francis Drake was a jolly good chap, say) and unpicking it until it falls apart (Drake’s piratical pursuits included trading in slaves), all while taking a couple of diversions down (literal) English byways and speaking to some of its people, both well-known and not. Whereas Another England is part memoir, part manifesto, but also a guided tour of some of Lucas’s favourite works of English literature. Its method is more to suggest how, instead of relying on myths about Magna Carta and empire and the EU, we can spy—and aspire towards—a new England through the examples offered by the nation’s novels, poems and other texts. She quotes the British-Nigerian writer Ben Okri to the effect that “Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves.”

This makes Another England not just another book by another politician; if only more departing MPs would write about Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton (1848) and John Wyndham’s The Kraken Wakes (1953)! But the emphasis on literature also makes it a strange book. Yes, there may be lessons for how we ought to cherish and protect the English countryside in the poetry of John Clare—but a different politician, with different points to make, could claim that Enid Blyton’s Famous Five books show how the policing of England’s coastlines should simply be left to groups of pre-teen vigilantes, at much lower cost than the current arrangements.

Besides, parts of the textual analysis veers towards blandness—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) is invoked, pace climate change, as an exploration of whether “humans fully understand the consequences of their untrammelled pursuit of science and technology”—or just plain oddness. Show me someone who claims, as Lucas does, that Robin Hood has never been transplanted out of England—in the way, she says, that the film Seven Samurai (1954) was transplanted out of Japan for the 1960 western The Magnificent Seven—and I will show you someone who hasn’t seen the Sinatra-starring, Chicago gangsterland-set Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964).

Lucas’s strength as a writer—and perhaps also as a politician—is her fierce reasonableness. Despite picking the literature that makes her points, and despite clearly yearning for a progressive English national story, she does not sweep away other perspectives entirely. Towards the start of Another England, she lists some of the “myths, half-remembered fragments of history, nostalgia and outright misrepresentation” that make up our national consciousness: England’s victory in the 1966 World Cup, Dad’s Army, Dunkirk, the Falklands and more. “The ‘story’ works,” she adds, “because there is so much in the individual stories from which it is constructed – the creativity of the Enigma code-breaking, the courage that liberated the Falklands – that is genuinely admirable.”

Baldwin and Stears’s book is also at its best when it is at its most undogmatic. The chapter about Greenwich in London takes as its myth not a right-wing hero or ideal, but the notion of “England shedding history and bypassing time so that it could stride unburdened into a global future”—which is, the authors note, “most obviously associated with Tony Blair and his New Labour government”. What follows could hardly be classed as a takedown of Blair, but rather a firm prodding-away at our former prime minister’s impatient desire for an entirely new England, more futures markets than market towns, more cyber than Carry On Up the Khyber. Not only did the great, globalising effort predate New Labour—with Margaret Thatcher’s governments laying the groundwork for the sky-scraping houses of international banking that have arisen alongside Greenwich—but the results of that effort have been patchy, at best. As Blair himself predicted, in his 1999 party conference speech, the “forces of progress” would have to do battle with the “forces of conservatism” in the 21st century, though he might not have foreseen the outcomes of each individual encounter. Globalisation, meet Brexit. Immigrants, meet firmer borders. Money markets, meet Liz Truss.

If there is a Magna Carta for the current century, then it may be an open letter written by Gareth Southgate

So what can be made of it all, of this England? If there is one new text—a Magna Carta—for the current century, then it may be an open letter written by the English men’s football manager, Gareth Southgate, under the headline “Dear England”, in 2021, ahead of his team’s participation in that year’s Euros. It was a letter that spoke of Southgate’s own pride in “Queen and country”, but also of a younger generation whose “notion of Englishness is quite different from my own”. “I understand that on this island, we have a desire to protect our values and traditions,” he continued, “but that shouldn’t come at the expense of introspection and progress.” This letter is referred to, with approval, in both England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country and Another England. It has lent its name and its author to a play by that other great summariser of modern England, James Graham.

But perhaps “Dear England”, too, is a myth—or mere comfort. When it comes to the future, with its persistent challenges of populism, national fracture and technological disorder, something more solid than words is required. Something, perhaps, like an English parliament? “I don’t want progressives to fall into the trap of opposing calls for an English parliament,” writes Lucas, noting how it is the right—even the far-right—that has so far led the calls for such an institution. There certainly is a positive case to be made, and not just for England. The introduction of an English parliament could result in more powers being granted to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; it could see clearer boundaries around what counts as a UK matter to be dealt with in the UK parliament; it could inspire a rethink of the voting system so that our representative bodies are more, well, representative. Lucas quotes John Denham, another figure of the left who has paid great attention to Englishness: “Only when England can see itself as England will it be possible to challenge the idea that Britain is England and allow the other nations to feel like partners of equal status.”

In this respect, we might think of England as the thick end of the wedge. If lasting change is to be made in the UK as a whole—the sort that will keep that kingdom united—then change in England, the biggest of the home nations by population and political footprint, needs to be hammered through as hard as possible. Just like the final penalty, courtesy of Jude Bellingham’s right foot, that will win us the Euros on 14th July.