Flicking through Aidan Koch’s Spiral and Other Stories, her first collection with New York Review Comics, feels so intimate as to be intrusive; it’s as if we’re peering into a private journal or sketchbook. People appear to us like stencils from an otherwise largely white page, with blurry clouds of pastel or watercolour giving just enough distinction to denote trees, rivers, the walls of an apartment, clothes. Backdrops dramatically change from page to page for no particular reason other than (probably) the brush just falling the way it did. It’s a rare sort of style for a comic, a genre where the demands of narrative are more typically met by a kind of smoothing out of the image: thick black outlines and full areas of colour, say, applied with such regular consistency that our eyes barely register the gutter between one panel and the next. Spend enough time with such perfect reproduction, though, and things can start to feel a little too mechanical. With some comics, at least, it’s easy to feel removed from their human progenitor altogether.

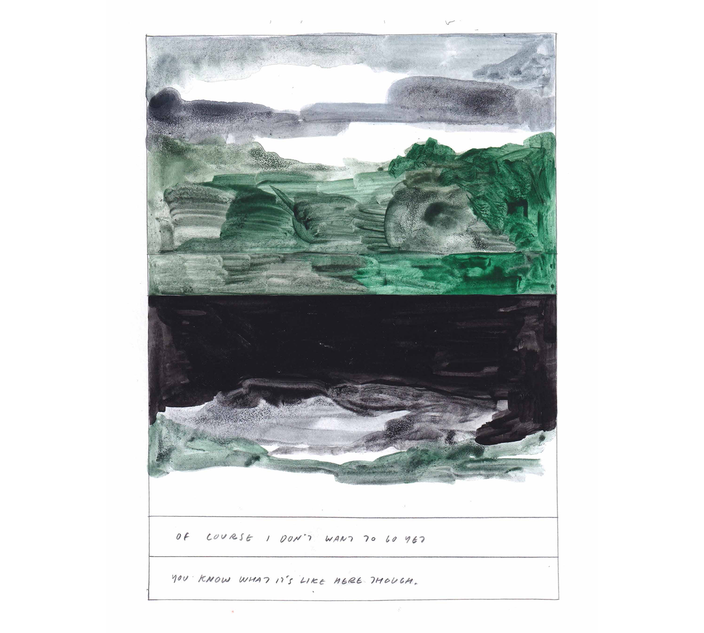

Yet with Koch we have the opposite thing going on: we’re almost too close to the point of creation. In her washes, we can practically follow the direction of her brush as it fills the page up and down. Lines sometimes overstep the corner of the panels, where she has taken her pencil too far over with a ruler; in the gutter are accidental smudges, perhaps where her hand has been leaning. Combined with how everything in this book, including the blurbs and front matter, is written in Koch’s own tight, slanted handwriting, and you are left with a mass-produced object that manages to feel deeply personal and idiosyncratic.

It’s also the perfect form for Koch, who uses narrative more as a repository for mood or feeling than as a vehicle to deliver a “story” in the conventional sense. Here we are more inclined to linger on each page and decipher its textures; the propulsive energy that would normally drive us to keep turning has been defused, replaced by something quieter and more contemplative.

This is also helped by how each plotline is simple enough to be summed up in a sentence. In the titular story, a nameless woman visits her two friends, Lise and Yann, who are looking to build a new farming homestead on Yann’s recently inherited land. In another, “A New Year”, two friends recall a local legend of a spirit tree hidden somewhere in the woods nearby right before the bells on New Year’s Eve. And so on. Yet each offers just enough material to allow Koch to explore her main interests: folklore, nature, alienation, friendship, our relations with the non-human world. Uniting them is the way her characters find themselves constantly beholden to or fighting with some greater undercurrent, invariably linked to nature. “It’s said humans have an evolutionary preference for places like this,” says Yann as he shows his friend around his new homestead: “The combination of some trees, some elevation, some water. It feels safe.” In the final story, “Man-Made Lake”, a man speaks to a therapist about a former life he believes to have had before becoming human: “I was also the water,” he says, “My cells were part of everything.” “We have to end here,” says the therapist, “but I think it’s important to continue talking about this.”

This sort of holistic ecology can be risky territory, not least because it’s well-trodden within environmental circles. But Koch—who lives close to nature in California’s Mojave Desert and sees comics as a means “to position and support the environment as a significant character in our lives”—knows better than to present this idea as either platitude or solution. Our alienation from nature is the most immutable fact of our modern lives, the question we can neither answer nor afford to ignore—“it’s important to continue talking about this.” But there isn’t anything to be solved, per se—there isn’t anywhere for us to “go”. All we can do is sit for a while with that predicament, and hopefully—like slowly contemplating the page of a book, free from the habitual urge to turn over—we’ll reach something like understanding.