On one wall hangs an old American military tent from the Second World War. Flattened, the tent looks like a paper party hat that is yet to be opened out. Positioned diagonally across this unlikely canvas, from bottom left to top right, are a series of brightly coloured letters; it is only when you are standing close up that you realise they are made from hundreds of stitched-in buttons. Together, the letters make a phrase: Go fuck yourself.

It might not seem like it, but with this work—as with the many others on display at London’s Lisson Gallery this February—we find ourselves in classic Ai Weiwei territory. The irreverent defacing of a historical object; the elevation of mundane and mass-produced objects; profanity as political statement. These are the themes upon which Ai has built his reputation, the constants in a body of work now spanning more than four decades and encompassing installations, architecture, opera, films, books and more.

“I like to use historical objects for other purposes,” Ai tells me one sunny winter’s day at the Heong Gallery, part of Downing College in Cambridge. These objects, he says, are like his version of the readymade. Designed for a specific purpose and at a specific moment in time, they couldn’t be further from a blank slate; already latent with so many assumptions about how they are meant to be used and what they are supposed to mean, they are instead a known quantity on to which other ideas—“a construct or a strong, sometimes even contradictory argument”—can be imposed.

At Lisson, the objects Ai has appropriated or reinterpreted range from Second World War paraphernalia and Chinese porcelain artefacts to works by Gauguin and van Gogh. But perhaps the most pervasive readymade in his recent work is something much more discreet. “ I often buy materials which I associate with our human history,” he tells me of his collection of buttons, which he acquired from the A Brown & Co factory in Croydon when it closed down in 2019. Buttons, he says, hark back to the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, evidence of the repetitive perfection that could now be achieved at scale; as parts of our clothing, they are also more intimately related to our bodies than other mass-produced objects. By sewing them to fabrics other than clothes, Ai hopes to create narratives that might not otherwise have been possible or obvious—between words of this period with the connotations of another, for example. (The phrase on the tent, it turns out, is a reference to Elon Musk.)

It took Ai many years to grasp the true scale and meaning of what he had acquired from A Brown & Co. “The buttons stayed there as a problem for a long time,” he says, “but I often create a problem before I know how to solve it.” After employing two people to individually categorise them—30 tonnes of them in all, taking up 60 cubic metres of studio space—Ai discovered he had around 9,000 unique varieties, made from bone, mother of pearl, plastic, metal and wood. Slowly, we begin to get a sense of the paradoxical nature of this unassuming object: something that is both diminutive in form yet collectively monumental, made by machine yet stitched by hand.

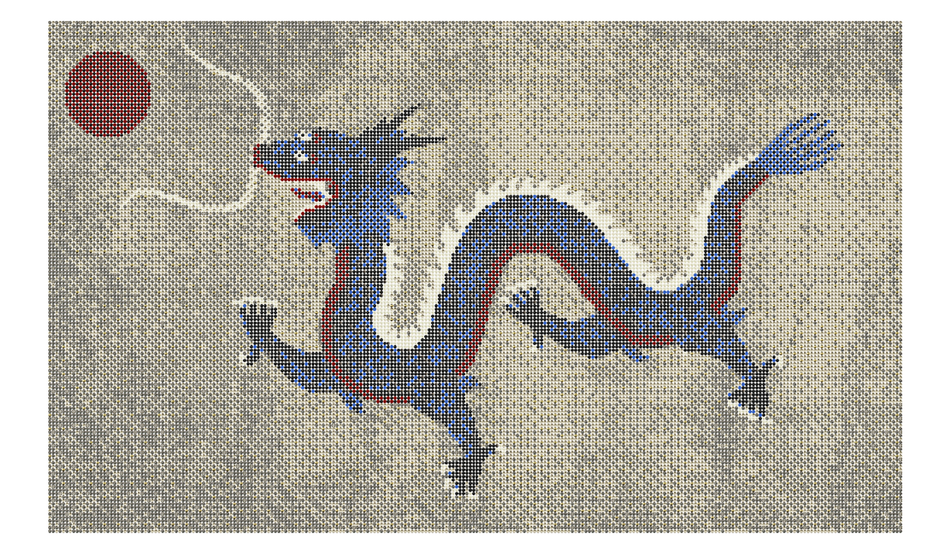

Unlike many contemporary artists, who seldom offer even an acknowledgement of the vast workshops of technicians and craftspeople that make their art possible, Ai frequently draws our attention to the human labour involved in his artistic process. Most of his artworks are painstakingly made by many hands over long periods of time. Just like his famous sunflower seeds—in which 1,600 artisans crafted each porcelain seed individually over two and a half years—one of his earliest efforts with the button collection involved former factory workers from Shandong province, in northeast China, making giant national flags by hand stitching the buttons to sheafs of fabric; one US flag, he tells me, consisted of 600,000 buttons. (In this Lisson show is the dragon flag of the Qing Dynasty, no doubt made up of a similar number.) In other instances, such human grind might remain invisible, at best reduced to a cold statistic on a gallery plaque. Here, however, you can’t help but marvel. Oh my God, how long did that take? Just look at all that work!

The point of all this is to show how much we’ve done to dehumanise the manufacturing process—when, in fact, real human labour lies behind every product; nothing just “appears” on our shelves without human involvement or human consequences, even in this age of mass production and automation. With this in mind, some of Ai’s thoughts on the future of art in the face of artificial intelligence can sound surprisingly upbeat. In a lengthy op-ed for the Guardian early last year, he argued that art was in no danger of being supplanted by machines. “AI, despite all the information it obtains from human experience, lacks the imagination and, most importantly, the human will,” he wrote.

“The machine is always trying to perfect its outcome,” he tells me at the Heong Gallery. “As humans, we never really want just a perfect answer. We want to give meaning and to insert a personal interpretation into the answer.”

The reason for Ai’s optimism comes down to his view of art itself, which can be split into two parts. One, that art is an expression of our individual humanity, a product born of an inner emotional truth. The other, that it is a means of subversion, a process of “unlearning” by which received wisdom may be picked apart and challenged. Both of these things are unachievable by AI, which possesses no individuality or interiority and, by definition, can only learn in more elaborate ways, not unlearn. In sum, AI may well be able to match the technical prowess of many human hands, but that does not mean it can make or do art in any meaningful way. (It should be noted, at this point, that the title of Ai’s Lisson show—“A New Chatpter”—and its press release were both written, tongue firmly in cheek, using generative AI.)

All the same, Ai believes that the climate for making art is more inhospitable now than it was when he was starting out. “Certainly, it will be a bigger challenge for someone wanting to be an artist in today’s life,” he says. “The world has become so flat. Existing values and judgements are becoming so solid, because we’re living in a society not marked by philosophical thinking, but rather entertainment and comfort.” But this, he sees, is the consequence of something more old-school than AI: specifically, the continued encroachment on our right to privacy by the powerful. (In that sense, AI may have a greater influence as a means of making surveillance more sophisticated, rather than as a direct competitor to artists.)

“Art exists only because we live in the world with some deep privacy,” he says. “We have a curiosity to reveal or to solve. If there’s no privacy, there’s no guessing. If you don’t guess anything, everything is obvious.” We cannot reach that inner emotional truth that makes art meaningful without privacy, because it’s while in the depths of a private thought that we probe them. And we cannot be subversive if we are afraid of making mistakes, which Ai argues is the root of all human intelligence. It’s an omnipresent fear of exposure—of being judged or discriminated against for our mistakes in the public sphere—that engenders homogeneity and middling, meaningless art: “When there is no privacy, we are all the same,” he says.

All of this rings intuitively true. Though, with his emphasis on making mistakes—which was also present in his Guardian piece—I can’t help but wonder if Ai might also be alluding to something more personal here.

“This exhibition was supposed to happen two years ago,” he says, before referring to the onset of the war in Gaza in October 2023. Later that same autumn, Ai posted a comment on X in response to another user: “The sense of guilt around the persecution of the Jewish people has been, at times, transferred to offset the Arab world. Financially, culturally, and in terms of media influence, the Jewish community has had a significant presence in the United States. The annual $3bn aid package to Israel has, for decades, been touted as one of the most valuable investments the United States has ever made. This partnership is often described as one of shared destiny.”

In response to the post, Lisson quickly postponed the London exhibition, as well as others planned for New York, Paris and Berlin. “There is no place for debate that can be characterised as anti-Semitic or Islamophobic at a time when all efforts should be on ending the tragic suffering in Israeli and Palestinian territories, as well as in communities internationally,” the gallery said in a statement.

Later, the BBC reported Ai’s own comments about the incident: “When discussing correctness or wrongness, I must be wrong. I have always regarded free expression as a value most worth fighting for and caring about, even if it brings me various misfortunes... Incorrect opinions should be especially encouraged. If free expression is limited to the same kind of opinions, it becomes an imprisonment of expression.”

Although I do not broach the show’s postponement directly with Ai, it seems to me that its fallout is still present between the lines. In a separate question about what he hopes to achieve with the work he is producing now, as compared to his earlier days, he says: “ I don’t want to achieve anything. I just want to make sure I understand what kind of mistakes I have made before, what has to be done, and what has to be spoken about more clearly.”

As Ai’s own work shows, technology has provided us with a steady stream of new ways in which we might estrange ourselves from each other, since as far back as the Industrial Revolution. But no matter how we use technology today or in the future—or how technology, increasingly, makes use of us—the job of art remains the same. In the face of forces that would prefer it if we were just fodder for algorithms or cogs in a machine, art must be there to assert our individual, complex human nature. “We have to accept we are different,” Ai says. “We’re just as different as mice and the bees. We don’t want to become a creature that is all the same. Because that’s against the law of nature.”

“Ai Weiwei: A New Chatpter” is on display at the Lisson Gallery until 15th March