In the spare room of Joe Boyd’s apartment in west London, the contents of his suitcase sit folded and ready for packing. In a day or so, he will depart for the US, touring his book, And the Roots of Rhythm Remain, from New York to Texas, via Tennessee, California and Oklahoma.

Before then, he must complete the book’s audio incarnation—a challenge for any author, of course, but particularly for one of the world’s most renowned record producers; Boyd is famed for his work with Nick Drake, Fairport Convention and The Incredible String Band, not to mention REM, Toumani Diabate and Taj Mahal, among many.

“It’s hard for me to call the audiobook a pleasure at this point because it’s been so much work,” he says, sitting in his living room window seat. “It’s been 43 hours. But I wouldn't let anybody else do it, so it’s a cross that I have to bear. I listen back, and I go: ‘Wow, wait a minute, that needs a little more air between those phrases…’”

Writing And the Roots of Rhythm Remain was also a lengthy endeavour, taking Boyd some 17 years. Billed as “a journey through global music”, it carries us from an afternoon in New Orleans spent recording with the Cuban all-star ¡Cubanismo! to London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, where a group of musicians from Arnhem Land in northern Australia are on stage rhythmically banging rocks together as part of the second ever Womad festival. In between, we read of Nigerian drummer Tony Allen’s mastery of the hi-hat, Ravi Shankar’s first recital in New York, the tanchaz movement in Hungary and Mexican journalist Alma Guillermoprieto’s instructions for How to Samba—to name but a handful of Boyd’s anecdotes.

It is an astonishing work, balancing the meticulously researched with the beautifully anecdotal and casting music less as a medium to be divided by genre or geography, but rather a kind of mycorrhizal network, connecting us through endless threads of rhythm.

The book’s origins lay in those ¡Cubanismo! sessions, back in the winter of 1999. Boyd had conceived of the record, Mardi Gras Mambo, as a celebration of the links between the musical cultures of Havana and New Orleans. Both had grown out of Africa, he reasoned; both had been shaped by colonial slavery. He secured a grant to bring the Cuban musicians to Louisiana and drafted in local horn players, only for the sessions to stall.

“The problem was that they laid back on the beat with a sensual Big Easy cool,” Boyd writes. “Cubans, on the other hand, generate their sexy grooves by sticking to the task with rigour, the rhythm section meshing together with the precision of a Swiss watch.” But it sparked a question in Boyd’s mind: “How did their rhythmic sensibilities come to be so different?” One day, he decided, he would look for the answer.

By this point, Boyd was already uniquely positioned to investigate this mystery. His musical adventures started early—while still a teenager, he had invited bluesman Lonnie Johnson to play a house party in his hometown of Princeton, New Jersey. After Harvard came stints as a tour manager for Muddy Waters and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Then a move to London, where he set up the UFO Club—a short-lived, if legendary, counter-cultural hub for performers such as Pink Floyd, Soft Machine and Yoko Ono—and founded Witchseason Productions, which helped to define the folk sound of London in the 1960s and 1970s.

Much of Boyd’s biography might be viewed as a collision of instinct, happenstance and genius: he was the stage manager at Newport Folk Festival when Dylan went electric; he supervised the recording of “Dueling Banjos” for the soundtrack of Deliverance (1972); in 1987, he was in the room when the term “world music” was chosen by a record industry cohort as a way of categorising those albums that stores had previously filed away as “international folk” or “ethnic”.

It was an imperfect title but an important one; ensuring some kind of audience, distribution and remuneration structure for the artists in question, and a way of opening up the listening possibilities for record buyers—an increasing number of whom were white, middle-class and seeking music from other cultures. Over time, partly thanks to the globe-shrinking role of the internet, the “world music” term would come to seem othering and redundant, but for a good decade it served as a kind of riposte to an industry immovably bound to genre classification.

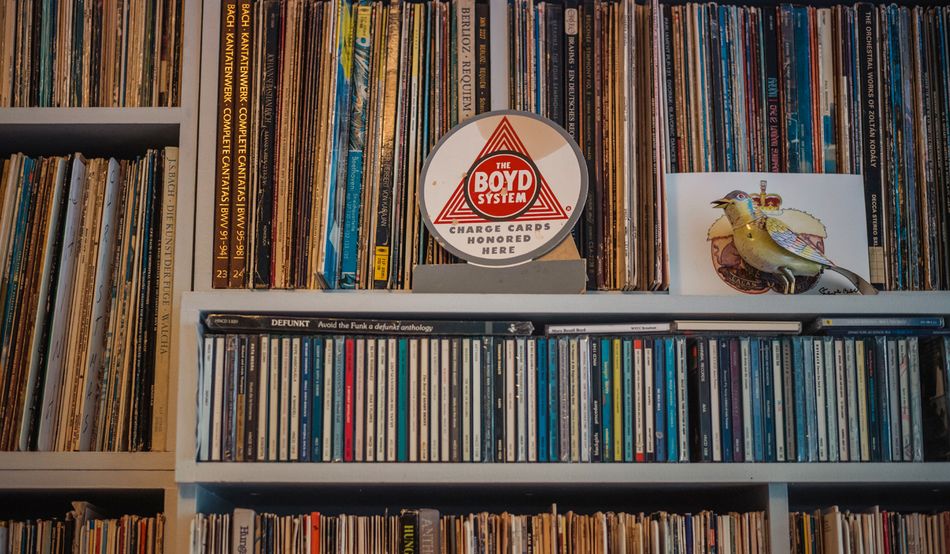

Boyd’s presence at that meeting was crucial. Some years earlier he had founded Hannibal Records, one of the first labels operating in this field. Hannibal was a labour of love and fascination for Boyd, a place to release records by Richard Thompson and Bert Jansch, but also Ali Farka Toure, Defunkt, Kanda Bongo Man and Ivo Papasov & his Bulgarian Wedding Band. Its ambitions were inquisitive and expansive, and established Boyd as something of an authority on the world beyond the Anglo-American pop charts.

It is these credentials that prompt one of the book’s finest stories, in which an anxious Paul Simon corners Boyd at a party in London and plays him the backing tracks to Graceland while singing the songs in his ear. “I think he was insecure about the record at the time,” Boyd says now. “He didn’t know what was going to happen when he released it.”

Boyd could see that Simon was in the potentially dangerous territory of musical fusion—Graceland took South African musical styles such as mbaqanga and isicathamiya and married them with rock and pop and zydeco. “I always say that most fusion is like peanut butter and jelly that falls face down,” Boyd says.

But Simon approached things differently. Already Boyd had admired the melded styles of songs such as “Mother and Child Reunion” and “Love Me Like a Rock”, and in this prototype Graceland he could hear the promise of something special. “The way Paul works, to me, is the right side up,” he says. “So many of his records don’t have the singer-songwriter strum in an obvious way. Paul takes rhythm, he goes for the rhythm, he starts with the rhythm, that’s why I like it.”

Boyd’s book takes its title from a Graceland lyric—a line from the track “Under African Skies”. “It’s all very solid to me that it’s a Paul Simon phrase that sums up some of the spirit of what I’m talking about,” he says. “The spirit, and the respect for these people. You feel roots. You feel history.”

In the beginning, Boyd was more concerned with melody. Growing up in Princeton, New Jersey, he loved harmonies, vocal groups, doo-wop. “I always felt that was what music was about, what I locked into,” he says. Later, he discovered that his paternal grandmother was a concert pianist who had studied with Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna. “Long after she was dead, I read about what the Leschetizky school meant,” Boyd says. “It was explained as playing the notes that carry the melody, making them sing, while at the same time giving equal weight to every note.” It sounded remarkably familiar to his own approach to making records.

He was reminded of this sensation again when he began writing—first, his 2007 memoir White Bicycles, and more recently with And the Roots of Rhythm Remain. “When I got to refining the prose, I definitely felt it was very similar,” he says. “Because you want to accentuate the important things, drop out the things that aren’t necessary and are cluttering it up, and deliver an emotional punch.”

Over time, he grew increasingly conscious of what lay beneath the melody. “[It was] watching the way that with a good engineer you can mic a drum kit,” he says. “And how, when you mix it, you start with the drums and the bass and you build everything up from that. I think that became more and more important.”

“I wish I could talk about the rhythm of words and the rhythm of music,” he continues. “But the funny thing is that I think my feeling about rhythm of writing and about rhythm in music is something that has come later on.”

By his own admission, he only began reading “properly” in his late twenties. “The first writers I remember loving I guess were EE Cummings and Vladimir Nabokov, those are two that in my university days I would relish reading—not for course, but just for the rhythms.” He loved Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise and Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory for its structure, language and “the mixture of big ideas and small details.”

But the book that has perhaps resonated most strongly with Boyd is Ann Douglas’s 1995 publication Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s. “It’s about the beginning of what we now understand as modernity,” he says. “And the threads that she shows in the book are that modernity came from a mixture of skyscrapers, Freud, Madison Avenue, black music and the hangover from the trenches of the First World War. Those five things came together. It’s a book that almost after every sentence, certainly after every paragraph, I had to put it down and think about it.”

To spend time in conversation with Boyd exerts a similar effect. It is to understand the spirit and variety of his career, the pulse of enthusiasm behind the releases on Hannibal—and it is something akin, too, to reading his book: a desire for you to hear something, to understand both its context and connections. One might start talking about a dinner with Caetano Veloso, but end up discussing the nyckelharpa played at a Nick Drake tribute concert in Norway. A memory from the days when Hannibal was “teetering on the edge of bankruptcy” might flow into the story of the time he secured a publishing deal for Joni Mitchell. Or a discussion of the revived London jazz scene and the Church of Sound in Clapton will find its way to the wonder of evenings spent listening to polyphonic a cappella groups in Gjirokastër, Albania.

The inference is quite clear—there are connections everywhere, scales and melodies and folk tales and instrumentation. A recurring theme in Boyd’s approach is how music often stands as a rebellion against oppression. “There are many threads that go through the book,” he says, “[But one is] how there is no such thing as a pure culture and how brutally we have treated the people that have given us the music. Africans, Roma, how the Congolese could create such beauty in the face of Belgian occupation… western popular music is shaped by these cultures.”

He points out that the book ranges from the Ancient Greeks to nigh-on the present day. “I guess I’m a sucker for history,” he says. “And there’s an element of this book which is sneaking history in front of people by telling them about music.”

Boyd is keen to point out that the book would likely not exist at all without the assistance of his wife, Andrea Goertler. The pair met 10 years ago, at which point And the Roots of Rhythm Remain was well under way, but the days of hard slog had yet to begin. “She didn’t quite realise that she was marrying a book,” Boyd says.

“The first few years I was doing a lot of other things and writing when I felt inspired,” he explains. He had fairly breezed through chapters one to eight, clear on their content and how he hoped they might sound. But with a deadline looming, he wondered how on earth to begin its concluding chapter. “I didn’t want to start getting generalised and writing big sweeping statements and academic summaries,” he says. “In the end, I think the reason chapter nine works is because of Andrea. The image that I bring to mind is of one of those corny First World War stories where the guy goes out into no man’s land and puts the wounded pal on his back and carries him back to the safety of the line. I felt a bit like that. I was so exhausted.”

Since the early days of their courtship, Boyd had often read aloud to her—their first book was Bruce Chatwin’s On the Black Hill. Then he began reading his own work, eager to see her response. “Sometimes it would be a thing that I just half an hour before read on my computer and thought, ‘Oh yeah! I really nailed it!’” Boyd says. “And then I read it out loud. And she’s sitting there looking at me and she’s not scowling or anything, but you feel that it’s not right. It’s with that awareness of the listener.”

Goertler’s role in And the Roots of Rhythm Remain might be described as the producer’s producer. Sometimes, when Boyd was floundering and at his lowest ebb, she would gently offer a solution. “She would say: ‘There’s a good paragraph here and that sentence isn’t bad, and if you put these two together you might have the beginning of the next, why don’t you try that?’” She was always right. “All along, Andrea has been my number one reader.”