The studio for Smoking Dogs Films, in London’s Wood Green, is essentially a large white box with a few small, offshoot offices partitioned by glass. It was almost entirely empty when I entered, save for a long white table in the central space where the artist John Akomfrah—in a black mandarin collar shirt, an olive scarf draped, louche, over one shoulder—had been holding court for the day, one journalist at a time.

This presentable emptiness belied the fact that the last five years have been a very busy time for Akomfrah: several new video installations, his first German retrospective. There has also been the matter of his gradual “acceptance” by Britain’s cultural establishment: admittance to the Royal Academy of Arts in 2019, a knighthood in 2023. Then there’s the reason we were speaking: his invitation from the British Council to represent Great Britain at this year’s 60th Venice Biennale.

One thing about Akomfrah not adequately captured by the glut of press photography that has come out since the Venice announcement—always stern, looking off into the middle distance, serious—is his natural garrulousness.

“If you had been here just a few hours before, you could’ve taken some fruit away with you!” he laments, gesturing to the empty crates stacked beside us. The fruit, most of it tropical, was used as part of another photoshoot; he alludes to some connection to his Venice installation. Speaking with him in March, a month ahead of the opening, Akomfrah was unable to talk in detail about the Biennale work just yet. For the time being, I was left to make what I could of these oblique references.

In the conceptual framework devised by the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall in a 2004 lecture, Akomfrah—who frequently cites Hall as a major influence, having made two films about him and his ideas—would sit within the second of three “moments” of postwar black diasporic art. Unlike the first, composed of those born in the colonies who arrived in the UK as adults via routes such as Windrush, the second came mostly as young children and were educated here. (The third moment, the British-born children of the second, was at that time still coming of age.) As such, Akomfrah’s concern as an artist is how to straddle this world between worlds, where homeland is not simply an abstract past filled by dead ancestors but somewhere firmly planted within living memory. What kind of identity is forged by those who do not belong fully anywhere? What does it mean for identity to be fluid yet also intangible? For Hall, identity was the unfinished conversation, a push-and-pull with the soul, a kind of dialectic of the self. Akomfrah, through his art and film, has made it his life’s work to keep that conversation going.

Akomfrah was born in 1957 in Accra, Ghana, almost exactly two months to the day after it became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence from a colonial power. His parents were heavily involved in anticolonial political activism: his mother had met Malcolm X and his father worked in the cabinet of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first independent leader. Amid rising turmoil in Ghana in the mid 1960s—which would culminate in Nkrumah’s ousting by military coup in 1966—Akomfrah’s father was shot and killed. Out of fear for their lives, Akomfrah’s mother took the family and emigrated. After a brief stint in the US, they wound up in London. “Diasporas are created as these violent eruptions of the conceptual,” he told the curator Ekow Eshun in 2016. “I’m only in the UK because my old man took a bullet.”

Akomfrah was nine when he arrived in the UK. “Growing up in London in the 1970s, the question of visibility was always uppermost,” he tells me. “There was always that sense you were being targeted or surveilled.” And yet, he had no choice but to carve out a space for himself in this new national culture that treated him with suspicion—he and his family were exiles, after all. They had not merely left their country of origin. Ghana had rejected them.

“John was next in line to be a king!” Or so Arthur Jafa, the American artist and longtime friend of Akomfrah, puts it to me. Early on in their friendship, Akomfrah told Jafa a story—now much mythologised—about his grandfather, a spiritual figure of sorts in Akomfrah’s family. He owned a ring that had been passed down from generation to generation, for hundreds of years. Akomfrah was next in line to receive it. Just before he left the country, however, his grandfather chose not to pass it on. Instead, he put it in his mouth and swallowed it.

“John said to me, ‘That was the end of that. It was over,’” says Jafa. “But I told him that was a misreading.” He recounts to me what he said to Akomfrah then: “By swallowing this ring, he was saying to you: ‘I’ve taught you everything I know, but I can no longer give you the map. The terrain you’re going to have to navigate is going to be radically different from the terrain which I navigated’.” The power was now Akomfrah’s to create his own monuments and memorials to the past.

To some extent, Akomfrah’s formative years in Britain bear out Jafa’s interpretation. Perhaps without even knowing it, as a teenager he was already probing for the right tools to make those monuments—and found them in a pair of institutions within short distance, to the east and west, of the south London community in which he and his four brothers grew up and went to school. The first was the Tate Gallery on Millbank. The other, the Paris Pullman cinema on the Fulham Road.

While the Tate entranced him with its English landscape paintings by Constable and Turner, it was film that quickly became Akomfrah’s obsession. “The thing I loved about film was the experience of it,” he explains. “It was this sense of being in a place where you were part of a crowd but also completely alone.” If bucolic English painting made him aware of who or what was being omitted from the story, then cinema taught the opposite lesson: how art can create a space of inclusion, free from prejudice. “You can’t hide blackness. You carry it like a stigmata,” he says. “But there were a few places you could literally disappear, and the cinema was one of them.”

Beyond questions of representation, Akomfrah also began to discover a more philosophical dimension sitting behind the moving image. “It’s this weird record of time, because everything that you’re looking at is already gone, it’s dead,” he says. “I became fascinated by that sense of cinema as a kind of indexical machine, if you will. Everything in cinema is archived.”

Yet despite these artistic stirrings Akomfrah chose not to attend art school, instead opting for sociology at Portsmouth Polytechnic. But it was there he and some new friends formed what would become one of the most consequential groups of black British filmmakers of the 1980s: the Black Audio Film Collective.

Akomfrah was the group’s principal director. After a move to Dalston, east London in 1983—and just a few experimental short films to its name—the group was approached by Channel 4 to produce its first feature-length documentary. Around about the same time, in September 1985, tensions between the local community and the police broke out into riots in Handsworth, a racially diverse area of inner-city Birmingham.

Released just over a year after the riots, Handsworth Songs has all the initial signs of what you could say would become Akomfrah’s directorial motifs: an experimental collage of found footage, news reportage and still imagery; scenes of police beatings interspersed with interviews of the people in Handsworth; an ominous, sometimes discordant soundtrack, in between cryptic voiceovers; a non-linear narrative arc, with no real beginning or end.

“We were talking about a moment when people were saying, ‘Why are these people rioting?’” Akomfrah says. “The idea was that somehow the rioting was foreign to English soil. Songs was an attempt to refute that.”

Dorothy Price, a curator at the Courtauld Institute and the Royal Academy, remembers the riots well; she was at school in Birmingham at the time. “If you put a lot of people together in a small, underfunded place with no opportunities and no prospects, there’s going to be a revolution, right?” she tells me. “But, in the media, it was essentially reported as ‘troublesome people of colour making trouble’.” The strength of Handsworth Songs, she argues, is that it gave another perspective on the riots from what was being presented in the national press. But it did so not by conveying a message or making a “point”, but by humanising those affected.

Although the documentary was quick to gain critical traction, not everybody was convinced. “People are calling it multi-layered, ‘original’ imaginative, its makers talk of speaking in metaphors, its director John Akomfrah is getting mentioned around town as a talent to watch,” wrote Salman Rushdie for the Guardian in 1987. “Unfortunately, it’s no good.”

Rushdie’s main bone of contention was that Songs’ bricolage effect did not really say much about Handsworth’s people; it was too disjointed, too unwieldly to offer an alternative to what was being said in the media. “There’s a line that Handsworth Songs wants us to learn. ‘There are no stories in the riots.’ It repeats, ‘only the ghosts of other stories’. The trouble is, we aren’t told the other stories.”

Spend any time reading analysis of Akomfrah’s work and you’ll find this is a common criticism. His insistence on letting things speak for themselves; his abstaining from straightforward narrative; his blending of disparate images whose union can be difficult to decipher; all of these things make an Akomfrah film a very different viewing experience. Part of the issue is that “story” does not quite cover it; what he is trying to elicit is more a feeling, a mood. “Of course, black artists deserve something more from us than mere celebration for having managed to say anything at all,” wrote Stuart Hall in a refutation against Rushdie in a letter to the Guardian. “But subject and experience don’t appear out of thin air.” Experience is not merely a story we make up; it is much less straightforward than that. And while Hall himself didn’t think Songs was “perfect”, he recognised in it an attempt to articulate a new way of speaking about the black British experience—one that, as Akomfrah knew himself, remained highly contentious and even, in some ways, inchoate.

Another thing that’s striking is that—despite some consensus on the politics of Akomfrah’s work—he himself seems disinclined, even opposed, to looking at things in that way. Jafa recalls to me another conversation he had with Akomfrah—at a house party in Brooklyn in the 1990s—in which they ended up debating whether it was even advantageous to call oneself a “black” artist. “He was resistant to the term,” Jafa says, “which I thought was incredibly ironic, given the name of the group was Black Audio Film Collective!”

“The nature of the political is such that it’s a totalising narrative, it needs to feel as if it’s in charge of everything,” Akomfrah says. Perhaps reminiscent of his experience in the Paris Pullman, the most important thing is to let the viewer be free to make up their own mind. Genuine conversation means allowing room for what you can’t predict. Unless you want to control what the other person is saying, you need to accept the unexpected, to leave open the chance for things to get discursive, meandering, for the topic of conversation to get derailed; only then might you come across something completely new.

Then again, another reason Akomfrah might be hesitant to nail any overt political colours to his artistic mast might be that the political was and remains deeply personal for him, in a very literal sense.

In 1988, Akomfrah returned to Ghana for the first time since his exile to direct a new feature film with Black Audio called Testament—incidentally about a Ghanaian who returns to Ghana after 20 years of exile following the 1966 coup. He was eager to visit his father’s grave, which he had not been able to see before he left. It was there, standing in the local graveyard—as he recalled in an interview back in 2014 with Carroll/Fletcher gallery—that “the full outline of the tragedy was in front of me”: countless graves desecrated and looted for valuables, among them his father’s. “We had arrived at this situation where the state was so narcoleptic, was so indifferent to the living that it was prepared to turn a blind eye to the living literally disfiguring the dead.”

There were no memorials to be found in Ghana anymore, and Akomfrah left the same way as he arrived: with memory alone.

In 1998—and countless more films directed and produced later—Black Audio amicably disbanded. In its place, Akomfrah formed Smoking Dogs Films with two other former members of the collective, David Lawson and Lina Gopaul (to whom he was by then married).

“By the time the collective folded in the late 1990s I got fascinated with, for the want of a better word, the ethics of multiplicity,” Akomfrah says. It all boiled down to a logical train of thought: “Songs is just a collage of different things. Some people liked it, some people hated it—oh, too many bits!—but then you realise you didn’t necessarily need a collage of a single screen. Why not grow the number of screens as well? Why have only one screen?” Since debuting his first multichannel video installation, The Unfinished Conversation, at the Liverpool Biennial in 2012, it has been his chief formula ever since.

“There just needed to be a modicum of a shared language between them, and they could talk to each other without changing what they are,” he says of having multiple films displayed simultaneously. “Suddenly, you can start to run parallel things at the same time. Suddenly you can go: whaling, slavery, military junta. Go!”

The allusion here is to Akomfrah’s three-screen installation Vertigo Sea from 2015, which takes as its shared language the common history we have with the sea. Starting, by way of example, with the actions of Captain Adolfo Scilingo, an Argentinian naval officer who threw 30 left-wing political dissidents out of a plane some 4,000 metres above the Atlantic, Akomfrah illustrates to me how one historical moment could follow on from, and have affinity with, the next: “First you think, okay, that Argentinian political prisoner will be dumped at sea. At that point, you can then remind people that the sea was also a place where slaves were thrown overboard when there were too many of them. It’s also a place where whales are harpooned. There are these moments of overlap between the subjects, but until those moments arrive they can afford to be vagabond, fugitive subjects. They can just go off and do their own thing.”

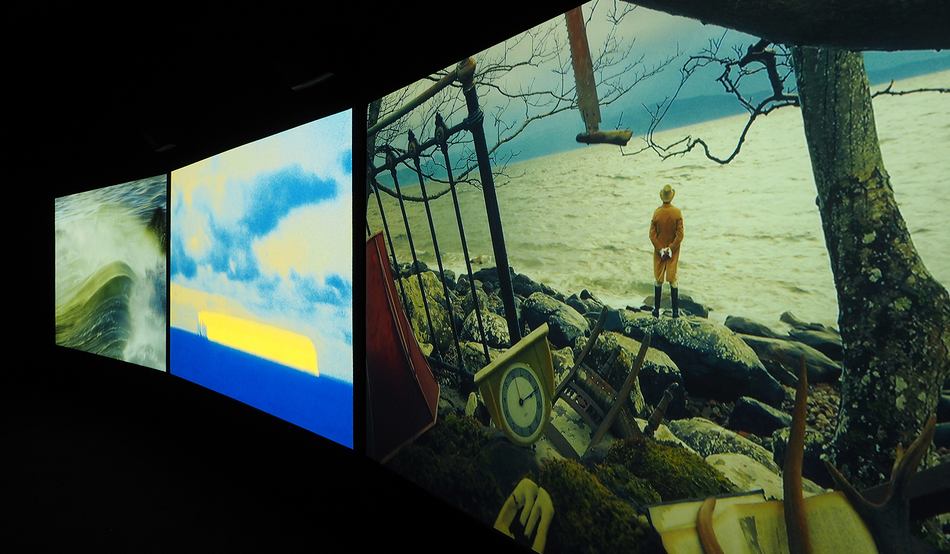

Vertigo Sea is an exemplar of Akomfrah’s thinking about multiplicity, and perhaps the most hauntingly beautiful work you will ever experience that tackles both the slave trade’s Middle Passage and ecological collapse. Split into chapters, its three parallel screens slide between wildlife footage, archival material, photographic stills and original “set pieces” filmed by Akomfrah himself: sweeping vistas of the ocean; schools of fish; an overcrowded migrant boat on an intrepid crossing; men shooting and skinning a polar bear; a man in a British red coat uniform surveying a landscape in a nod to Caspar David Freidrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog; the submerging sound, the slosh, of diving deep underwater… and all of this all at once, more or less.

Though, generally, it’s hard to talk too much about the specifics of Akomfrah’s individual works, because they operate more as a continuum than separate markers. Each work, be it The Unfinished Conversation, Purple or Arcadia, could be seen as an attempt to expand upon his cinematic vocabulary; searching, each time, to add a few new words to old sentences, until what he’s left with is a completely new way of speaking about some very familiar subjects.

Another difficulty is discussing this as a “solo” career. For virtually that entire time and longer, Akomfrah has worked with the same gang of close friends—Lawson, Gopaul, sound designer Trevor Mathieson and others. Jafa—who was Akomfrah’s cinematographer on the 1993 documentary Seven Songs for Malcolm X—tells me there was never another collaborator like him. “The most simpatico work I ever did!” he says.

“More than any other artist I’ve worked with, John embodies that collective sensibility,” says Tarini Malik, the curator of this year’s British Pavilion in Venice. She recalls to me a day she went to visit Smoking Dogs as they were busy at work on the Venice installation. “One small bodily gesture, and they understood that they were supposed to move or to do something. It was a little like watching a piece of music”—with Akomfrah as its “conductor”.

Whenever Akomfrah talks of letting in other perspectives to the work, he is not merely talking about an artistic device. “Finding commonality for things without necessarily reducing them to an amorphous, homogenous mass is the way, and not just for film,” he tells me. “But for society, for people.”

As you walk into the Biennale’s site at the Giardini in southeast Venice, chances are one of the first things you’ll see is the British Pavilion. A grand staircase invites the visitor up to a rectangular portico, with two balconies of white stone balustrades stretching off on either side from beneath the portico’s sextet of plain columns. Unlike some of the others nearby, the British Pavilion feels oddly self-contained, like a private country house: its shut-door, closed-off façade discourages the casual snooping of passersby. Quietly deferential yet resolutely aloof, it feels somewhat removed from the action while still being impossible to ignore.

This impression, I soon learn, isn’t entirely by chance. Malik tells me that the building sits, quite literally, at the highest elevation in the whole of Venice. “I didn’t even know until we were installing,” she says. “It was one of the Italian carpenters who told me.”

The discovery only underscored to Malik the balance to be struck between respect and dissent at an event such as this. “When John was first invited onto the project, both us were like: how do we subvert it? How do we challenge it? How do we make the fabric of it part of the conversation? But also, how do we pay homage?”

You don’t have to enter the pavilion to see how they have tried to tackle these questions.

Akomfrah has hung three vertical screens out the front, obscuring the Gran Bretagna plaque and much of the portico. The front door is closed off. To enter the pavilion, visitors must go through the basement at the back and work their way up. “That was a huge argument, but it was worth having,” Akomfrah explains. “That you could do a journey with the thing rather than the slightly strange, Wizard of Oz experience where you walk in and it goes, ta da!”

At the opening ceremony, under a grey spring sky one afternoon in April, a Rastafarian drumming group called Harambe perform at the top of the pavilion staircase, backed by the screens playing Akomfrah’s signature mixture of archival material, nature footage and photography slides. Akomfrah himself is nowhere to be seen. The musicians stop for a moment to offer what I’m later told is a remembrance incantation. “You, who are known by many names, we acknowledge you,” says one woman, as she intermittently drips water from a bowl over the side of the staircase. It’s as the group resume performing that, finally, I spot Akomfrah: hovering behind his screens, alone, head to the ground, gently bopping to the music.

The music stops again, this time for good. After a round of speeches from all and sundry within the British cultural establishment, Akomfrah steps out from behind the screens to deliver one of his own. His eyes are obscured behind his dark sunglasses, but still he is visibly moved; his bottom lip is quivering.

“Let me try and get through this quickly without crying,” he says.

“This reminds me of an old African parable. You’re paddling down a river, and at every stop you run out of something, but at every stop someone says, ‘Have this, have that.’ And that’s what this remarkable project has been like. There are collaborators in this crowd who I have known since the 1970s,” he pauses to look around, as much to hold back tears as to search for familiar faces. “I hope it’s been worth the investment.”

A length of red ribbon is hastily wound between the two columns on either side of the stairs. Less than a minute later, sharing a pair of scissors, Akomfrah and Malik cut it.

Akomfrah’s pavilion installation, Listening All Night in the Rain, is composed of eight separate works—or “cantos”—each tackling a separate but interrelated theme: colonial history, ecological disaster, the legacy of Windrush and so on. The number of screens varies in each room, from three to 12, amounting to around 31 hours of footage in all. From the cavernous basement, where the screens show footage obscured by running water, we rise to the upper floor, with each room containing an elaborate display of screens. Between the accustomed mix of archival material and nature footage is a new kind of image for Akomfrah, an elaborate sort of still life: amid reams of silk and other fabrics, men and women in raincoats lie with their eyes closed surrounded by an assortment of miscellaneous objects: rubber ducks in old baths; photographs; playing cards; a ticking metronome; a generous but carefully placed helping of tropical fruit.

The following day I meet Akomfrah for the second time in a small side room of the pavilion. “Whoops!” he says, as the window slams shut a touch stronger than expected. “Wouldn’t want the building to collapse now!”

“Yes, careful, John,” says Victoria, from Lisson Gallery.

Intuiting the opportunity to carry on with the joke, Akomfrah pretends to trash the room, lightly flailing his arms. “I’ve had enough!” he says, in mock outrage.

As Akomfrah eases into his seat, his transition lenses adjust to the dimness of the room. He looks extremely tired.

“How do you feel finally seeing it in situ?” I ask.

“Good question,” says Akomfrah, promptly adding: “Mixed, really.”

He quickly changes tack.

“It does mean now it’s out there and not a part of you anymore. But I’m immensely proud, both of the team and myself.” He goes through the origins of the title, which is a reference to an 11th-century Chinese poem by Su Dongpo. “I love this particular kind of early Chinese poetry because it has this sense of saying three, four things at the same time, but also of spending the minimum amount of time saying all of them, altogether,” he says. “I think, in the main, I’m happy with what we got. In the main. You can’t ever be completely satisfied.”

The Venice Biennale as a whole—which takes as its theme “Foreigners Everywhere”, with its emphasis on artists from marginalised or indigenous backgrounds—has received a lot of critical backlash this year, with Akomfrah’s own work the subject of especial ire in the British press. “Contextually incontinent” was the verdict in the Times. “It’s pretentious,” wrote Alastair Sooke in the Telegraph.

The Venice work is certainly Akomfrah’s most ambitious undertaking—and yet, here we are, with criticism remaining much the same as Rushdie’s in 1987: too many things happening at once, not enough story. When I put this to Arthur Jafa, he shrugs. “You could’ve said the same about James Joyce,” he says; what more is there to add? It’s the type of criticism to which experimental filmmakers have long become accustomed.

Yet, Venice has done something to Akomfrah that seems increasingly rare in an artist of his profile: it has made him vulnerable. The word visibility returns, clearly still “uppermost” in his mind now as it was in the 1970s; it’s telling that he compares exhibiting in Venice to the uncomfortable experience of primary school show-and-tell. “The teacher goes, ‘Come on up here, John Akomfrah, come stand here and tell the class something,’” he says. “And you go up, but you’re not really telling them anything, and no one’s listening anyway, they’re all just looking at you and going, ‘Oh, teacher’s pet! You’ve been selected and now you’re showing off!’” As if obliquely pre-empting the critical response to the work, he adds: “If people listen, then fine. If they don’t? Well, actually, there’s a whole bunch of people outside, in the playground, who are paying attention.”

I have one more question I was burning to ask Akomfrah. So much of his work is about looking to and learning from, even commemorating, the past. How does he hope future generations will look back on his own work, when it too is confined to the past, to archived history?

“It’ll be a bit like wandering into a room with an Italian fresco,” he says. “You don’t really know all the references. But the ambitions are apparent, as well as the sense of a desire there to speak to you. If that’s all that remains, that’s fine. Just the trace of that signature you’ve left…”

Akomfrah stops. He grins. “Look at him, arrogantly comparing himself to the Italian masters!” he laughs, the tiredness evaporating from his eyes as he transforms into the boy in the playground, tapping on the window, on the outside looking in. “The cheek of it!”