When in Venice, the American painter John Singer Sargent (currently the subject of a major retrospective at Tate Britain) was not content merely to work en plein air, preferring instead to paint en gondole—by gondola. With a canvas propped on his knees and his brush mirroring the broad strokes of the gondolier’s oar, Sargent painted Venetian life as he floated through it.

Unlike the more traditional depictions of Venice by other artists, Sargent didn’t paint “views”; he painted the invisible cities down every street and under every bridge. While Canaletto painted Venice in its Sunday Best, Sargent painted Venice in its Sunday Blues, the faces beneath their Venetian masks.

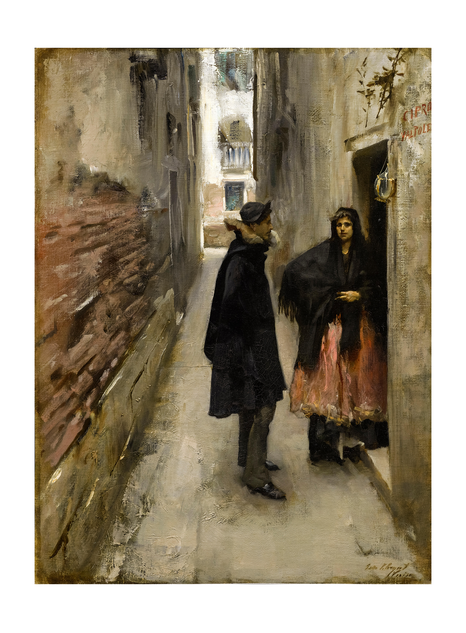

In this moody scene of two figures in a narrow street, painted when Sargent was in his mid-twenties, we almost feel as if we are intruding on a private conversation. The alley’s depth grants a certain intimacy; it guides our eye back and forth between the couple and the bright suggestion of Venice, between the fleeting moment and the enduring architecture, between the private life of individuals and the public life of The Floating City.

Sargent’s muted palette of greys and warm ochres speaks to the drabness of daily life in the 19th century, and yet the figures remain vibrant. With her right arm akimbo, we don’t know whether the woman’s left hand reaches for her shawl in warmth, modesty or insecurity. She is looking directly at us, and we notice that her tired coral skirt (made shabby and brownish by the loose, frenetic brushstrokes that would become Sargent’s trademark) mirrors the exposed brickwork. The woman’s male interlocutor wears a dark, hipsterish hat, upturned, and a black coat with a fur-trimmed collar. Seen only in profile and veiled by shadow, he seems to hold a distant gaze, almost dissociated, as though lost in thought. Even his stance suggests a shifting of weight from one foot to the other.

Sargent manages to harmonise the shift and the stasis of this labyrinthine city, charging this scene with countless possibilities, placing us not only at the crossroads of a street but also of shade and sunlight. Standing in a doorway, the couple appear to be on the threshold of a decision: of whether to stay or go, to love or leave. Judging by the look on the woman’s face, she too is uncertain of what will happen next.

In the early 1880s, Sargent was at his own crossroads. His friend, the writer Henry James, said this period carried the “uncanny spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn.” But style can’t be learned, only discovered with time. And here in this early Venetian Street scenes we see Sargent revealing his acuity for posture and gesture, refining his peculiar flair for capturing a whole personality in a look and a whole sensibility in a pose. It is a style that would later bring him fame and fortune.

By the 1900s, now embraced by high society, Sargent’s subject matter (and his colour palette) had become much more lavish, his sitters known names—such as the British aristocrat Helen Vincent, whom Sargent painted, also in Venice, in 1904. Unlike the anonymous woman on the street from the 1880s, there is no uncertainty in Lady Vincent’s gaze. But look closely and Sargent’s nascent style can still be seen in their shared hand-on-hip pose, while the subtle grit of his early street scenes has become the pearls draping casually as tinsel round Lady Vincent’s elongated neck.