As ways of opening an exhibition go, Alice Neel’s 1980 Self Portrait is certainly dramatic. Hung by itself in a small room at London’s Barbican, and illuminated so that it appears almost to glow from within, is a portrait of the elderly American artist, finished just four years before her death at the age of 84.

Neel sits in the centre of the canvas. A wash of blue behind her head puts her ruddy cheeks into sharp contrast. A patch of green sits under her left foot, while her right rests on a buttery yellow that grows into orange as it travels further up the painting; she has depicted herself as a part of the colours, the building-blocks of a portrait. Combined with the paintbrush in one of her hands and the rag in the other, there is no question of her vocation.

If this composition were not already impressive enough—a female version (or inversion) of Rembrandt’s aged self-portrait or Van Gogh’s painting of himself behind the easel—there is another detail that ought to be noted. At the age of 80, Neel chose to paint herself entirely naked. Only the overstuffed armchair on which she’s sitting appears to be clothed; in a bright blue, attention-stealing striped covering.

This self-portrait is typical of Neel’s style. The subject is naked, yes, but not humiliatingly or compromisingly so; Neel retains all the power as she gazes out at the viewer, comfortable in her sagging flesh.

At the time, Neel had been working as an artist for over five decades. Born in January 1900, she had aged—and painted—with the century. But, given the vagaries of the 20th-century art world, which prioritised male artists over women and abstraction over figurative realism, she did not achieve major recognition until the 1970s. According to one of her later sitters, the feminist art historian Mary Garrard, she appeared at the first national conference on women in the visual arts in 1972, and “took the podium” to discuss her work; armed with slides to show the crowd, she “would not stop, hungry for attention”. (In another brilliant anecdote from this same conference, she is reported to have “lifted her skirts and let loose in a corridor” when the line for the ladies’ loo became too long.)

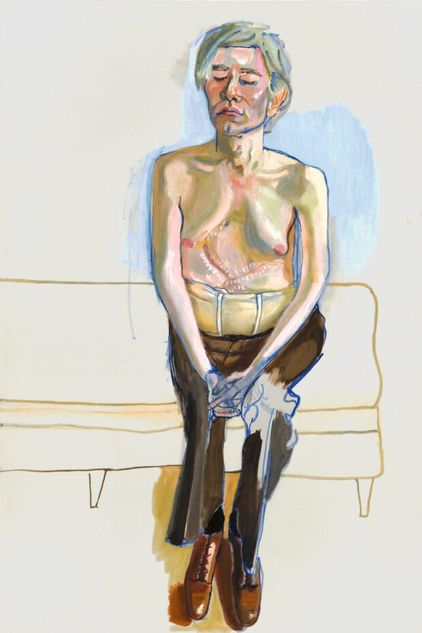

The paintings Neel is now most famous for—her 1970 portrait of the feminist critic and pioneer Kate Millett; her portrait of Andy Warhol from the same year; the brilliant, bold Marxist Girl from 1972—date from this period. The politics of second-wave feminism, of a changing America, expand across the canvases.

When talking about Alice Neel, her politics are mentioned so often as to make them a part of the background, the first wash of paint for each painting. Everyone knows she was a socialist; a member of the Communist Party; and the subject of multiple FBI reports (including one that accused her of being a “romantic, Bohemian-type Communist”). Her politics seem to provide a key to her works; lending an easily understandable meaning to the realism of each portrait—from the sparse linework of the unbearably sad Black Draftee (James Hunter) (1965) to the cool blue hues of Gus Hall (1981), a painting of the then-General Secretary of the Communist Party USA.

But when presented with the sweep of Neel’s work—a privilege afforded to those attending the current Barbican exhibition, Hot Off The Griddle—a far deeper understanding of the relationship between her beliefs and her art emerges.

Neel studied at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women when she was 21, then met and married the Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez Gómez. The paintings she made in this period—whilst living in Havana, Cuba—are impressionist in style. A mother and child sit in an embrace, their faces, limbs and clothing only gestured at with the thickest swipes of paint; her new husband, Carlos, sits in the dark of a bar, with the glass in front of him teetering on the narrow, translucent stem she painted; teetering, too, between realism and something far more dreamlike.

Neel’s life was marked by poverty and tragedy—her return to New York in 1927 was followed by the death of her first daughter, the breakdown of her marriage, and a spell in psychiatric hospitals. She moved, at that time, towards surrealism: her paintings show her friends naked, with comically outsized breasts and genitals. Her famous painting of Greenwich Village legend Joe Gould features no fewer than five sets of genitalia.

But from this world of sexual frankness and whimsy (in one small work on paper, Neel draws a man urinating into a sink as if he were pouring yellow liquid out of a penis-shaped jug), Neel’s art changed. After the Great Depression in 1929, President Roosevelt’s New Deal included a provision for the arts: the Public Works of Art Project. As part of this—and its successor, the Works Progress Administration—artists were paid a weekly wage in return for submitting a painting (but, crucially, not a nude) every six weeks.

It is no coincidence that this moment of socialism in America’s history—the recognition of art as a form of financially viable labour—coincided with Neel’s earliest overtly political works. She painted futuristic cityscapes that show people dwarfed by the architecture that contains them; scenes of striking workers being beaten by policemen on horses; and, perhaps most memorably, the dark, torchlit view of a protest against the rise of Hitler, entitled Nazis Murder Jews (1936).

In contrast to her later works—portraits that explore space, form, bodies and the limits of figuration—these paintings run the risk of seeming naïve: her people often look cartoonish, and the political clarity often trumps visual power. But they are more than just steps on the road to her later paintings. Here—painting in the years of the Popular Front, when communism was tied to a hopeful form of patriotism—Neel’s lifelong political commitments are laid bare.

In contemporary essays and conversation, Neel is often lauded for exhibiting modern progressive ideals: she was a pioneering woman who painted a broad section of society, from Spanish Harlem to pregnant women to the legendary sex worker Annie Sprinkle. Her art is, in both meanings of the word, “representative”. However, when the specific political context of her life and work is taken into account—the politics of the New Deal, the Popular Front, the rise and fall of Communism—this “representation” argument falters. Neel was hardly cherry-picking sitters who were different from each other, so as to signify different sections of society. Her portraiture—her “anarchic humanism”, as she termed it—is something far more vital: a desire to paint individuals as they were, living in the society and political structures that shaped them.

In Warhol’s case, he’s hemmed in, frail, and held up by a medical corset—and the portrait disintegrates into unfinished, fragile blue lines for his legs. This is a man who barely has a body beyond the one he dons for public appearances. In the case of the “Marxist Girl”, Irene Peslikis, the painting is a riot of strength: there are prominent muscles in her neck, her arms, her torso and under her blue work trousers. Only the typically Neel-esque thin feet expose any bodily vulnerability, while her face—all large eyes, and downturned curves—is far more revealing.

These paintings are exhibited amid a wealth of others, including Carmen and Judy (1972), in which the subjects are Neel’s cleaning lady and her breastfeeding, naked child. You can certainly see, here, Neel’s progressive politics on display, including her flirtation with organised feminism (she is quoted as saying, “I was women’s lib before there was woman’s lib”).

But, buried beneath the paint—and in the smaller, less star-studded rooms of the exhibition—is the deeper context for these works. Rather than just painting from positions that feel relevant and acceptable now—second-wave feminism and “representation”—Neel’s career and work were actually shaped by radical, concrete socialism and an utterly different side of America, from the New Deal to the Vietnam War.

This ought to be remembered as she becomes the latest poster girl for 21st century interest in women’s art.

● Hot Off the Griddle is on display at the Barbican until 21st May