This exhibition of early-20th-century art from Ukraine was organised with unusual speed. Many of the works now at the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, for In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s, are from Kyiv museums and were in obvious danger. Plans for a project of this kind, however, had been maturing for a long time; Russia’s escalation of the war was only a catalyst. Konstantin Akinsha, one of the curators, had compiled most of the catalogue before finding a location for the exhibition; in his words, he “put the cart before the horse”.

This lengthy gestation may in part account for the clarity and balance of the catalogue articles. In the past, many of the artists represented have been classified as Russian, even when they themselves emphatically asserted their Ukrainian identity. The curators’ corrections of this “appropriation” are admirably restrained. The painter and teacher Alexandra Exter, for example, was born in 1882 to a Greek mother and a Belarusian father, in a town then part of the Russian empire but now in Poland. Her family moved to Kyiv when she was three. In 1924, she emigrated to Paris. Katia Denysova sums up her career as follows, “She remained deeply devoted to Kyiv… She also acted as a tireless promoter of Ukrainian folk art. A true cosmopolitan, Exter never declared herself as belonging to any one nation.”

Exter taught or worked with many of the artists shown in this exhibition. Before the First World War she regularly exhibited in Paris. She met Picasso, Braque and Léger, and was particularly admired by Apollinaire. In the compendium Treasures of Ukraine, art historian Myroslava Mudrak describes her as “a courier of Modernism between western Europe, Russian artists, and her colleagues in Ukraine”. This, however, was only one of her many roles. She learned from cubism, but she employs its techniques in the service of a joyful vision that is distinctly her own. Most of her paintings are radiantly colourful, and some are humorous. Her collage Still Life (1913) incorporates scraps of newspaper advertisements in French, Russian and German; the largest is presented upside down, prompting the viewer to look at the whole painting from an upside-down perspective. In the large oil Bridge. Sèvres (1912) she limits herself to more muted colours but still creates a sense of light and of openness; even the space beneath the bridge is inviting. Interestingly, a great many of her best paintings are of bridges.

Exter’s openness extended to every area of the visual arts. In 1914, she co-organised an exhibition in Moscow of embroideries executed by Ukrainian peasant women based on designs by Kazymyr Malevych and other members of the avant-garde. The first public appearance of the movement known as Suprematism—it has been said—was as needlework. Sadly, few of these embroideries have survived, but this interpenetration of modernist and folk art is all the more interesting in the light of Malevych’s account of his childhood in rural Ukraine: “I watched with great excitement how the peasants made wall paintings, and would help them cover the floors of their huts with clay and make designs on the stove. The peasant women were excellent at drawing roosters, horses and flowers. The paints were all prepared on the spot from various clays and dyes… This was the background against which the feeling for art and artistry developed with me.” In a review of the 1914 embroidery exhibition, the perceptive contemporary critic Yakov Tugendhold wrote, “Here the non-objective colourfulness returns to its original source.”

From 1918 to 1920, Exter ran an influential art studio in Kyiv, aiming to introduce students to recent European artistic discoveries while highlighting connections between these discoveries and Ukrainian folk art. She also taught a course in stage design, which, in Denysova’s words, “produced a generation of theatre artists who would revolutionize the field not only in Soviet Ukraine, but also in Europe and North America.” Exter went on to work, in Moscow and then in Paris, as a stage and costume designer and as a book and manuscript illustrator.

The exhibition was organised with unusual speed. Many of the works are from Kyiv museums and were in obvious danger

Exter, Alexander Archipenko and many others trained at the Kyiv Art School. Two other cultural milieus also played a crucial role in the artistic life of the time. One was Chornianka, a vast estate near Kherson managed by the father of the three Burliuk brothers, two of whom are represented in the exhibition. Davyd, the best known, was important both as artist and as publicist; he has been called “the Futurists’ compère”. It was he who introduced Velimir Khlebnikov—the greatest of the futurist poets—to his fellow poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and the linguist Roman Jakobson. All the main futurist poets and artists paid long and frequent visits to Chornianka, and it was there that they planned many of their exhibitions and publications.

The flamboyant Davyd Burliuk is appropriately represented by his oil painting Carousel (1921)—one of several variations he made of the subject—a dazzling swirl of colour. The painting does, however, lose in reproduction, since its sense of movement derives mainly from the use of dense and varied impasto. Davyd himself wrote with characteristic brio, “I throw pigments with brushes, with palette knife, smear them on my fingers, and squeeze and splash the colours from the tubes… In my works you will find every kind of a surface one is able to imagine or to meet in life’s labyrinths.”

Burliuk and his colleagues initially called themselves “Hylaeans”—after Hylaea, the Greek term for the Scythian lands near the Dnipro’s outlet into the Black Sea. Identifying with the warlike Scythians was a way of proclaiming their opposition to the still-dominant Petersburg Symbolists, whom they saw as effete. Burliuk referred to himself as “a child of the Ukrainian steppes,” and he went on, “in my person Ukraine has its most faithful son. My colour schemes are deeply national… It would be a good idea to transfer a part of my paintings to Ukraine, my beloved homeland.” Nevertheless, he is still often labelled a “Russian futurist”.

No less important was Krasna Poliana, the home of the Syniakov sisters on the outskirts of Kharkiv. Vladimir Mayakovsky, Mikhail Matiushin, Boris Pasternak and Khlebnikov and many others stayed there. Lilia Brik, Mayakovsky’s muse, writes of these five sisters, all of whom were involved in one art or another: “They roamed the forests, wearing tunics, their hair loose. Their independence and eccentricity bewildered everyone. In their home, Futurism was born.”

Maria Syniakova’s bright, simple watercolours borrow from both Fauvism and Ukrainian folk art. The tone of Khlebnikov’s poems about the sisters is mystical and exalted. The many rhapsodic memoirs of Krasna Poliana are not mere whimsy or expressions of nostalgia; during the First World War and the yet greater destruction brought about by the ensuing Civil War, Krasna Poliana was truly a sanctuary. Khlebnikov was notoriously unworldly; the Syniakovs not only fed him but also saved him from conscription by the Whites in 1919. Khlebnikov died in 1922, aged only 36. But for Krasna Poliana, he might well have died of semi-starvation still earlier, before composing many of his greatest poems.

During the first years of the Soviet regime, the Bolsheviks bought the support of non-Russian nationalities by promising “freedom from the yoke of Russian oppression”. Ukrainian culture was briefly allowed to flower. From 1930, Stalin reversed this policy. A great many Ukrainian artists and writers were executed or sent to the Gulag—far more, in proportion to their overall numbers, than their Russian equivalents. The influential Mikhailo Boichuk founded a specifically Ukrainian school of Neoclassicism. Among the disparate sources he drew on for his frescoes, mosaics and paintings were Byzantine art, early Renaissance frescoes and the folk art of his native Galicia, in western Ukraine. Damned as a “bourgeois nationalist”, he was executed in 1937 and much of his best work was destroyed. The most powerful painting in this section of the exhibition is Jewish Pogrom (1926) by Manuil Shekhtman, one of Boichuk’s followers. Five figures in the foreground are clearly delineated, in bright colours. At least eight more figures in the background merge into the landscape in muted browns and greys, growing indistinguishable from the rocks as if disappearing from our memories; some, probably, are lying in a mass grave.

Another part of the exhibition features work by El Lissitsky and other members of the Jewish Kultur Lige. At its height, between 1918 and 1922, the Lige had branches in almost 100 towns and shtetls, administering schools, libraries, drama studios and music circles; it was a unique phenomenon, a moment of hope when it seemed that a progressive Yiddish culture—neither Zionist, nor traditionally religious—might be about to flourish. From 1920, however, the Lige was gradually taken under Communist control. Several of its best writers and artists moved to Warsaw, where a lively Yiddish culture survived somewhat longer.

The exhibition’s various strands meet in the section devoted to theatre. Les Kurbas was, along with Vsevolod Meyerhold, one of the most innovative directors of his time. His innovative Berezil company was both theatre and research organisation, similar perhaps to Peter Brook’s International Centre for Theatrical Research 50 years later. Kurbas was evidently as courageous as he was gifted. In 1930, the authorities forced him to stage Dyktatura (literally, “dictatorship”), a woodenly written justification of the authoritarian policies of the central government. Kurbas “recoded” the play, staging it as satire. Afterwards, he wrote, “We all know what dictatorship is… The obligation of every actor was to make every spectator understand that the rudder of history is in his own hands.” Kurbas was executed in 1937.

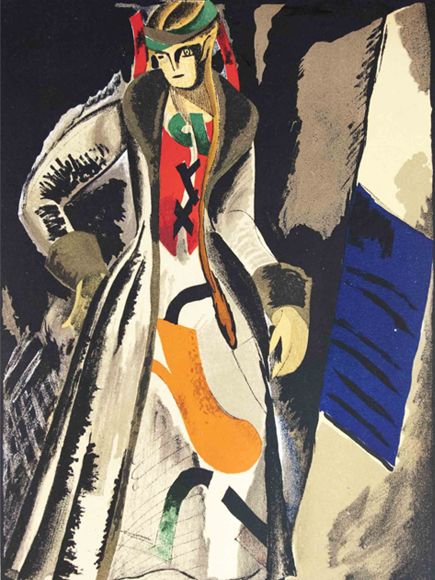

Several fine costume and stage designers studied under Alexandra Exter and went on to work with Kurbas. The most versatile was Anatol Petrytskyi. His costume designs range from the folkloric to the abstract and futuristic. He also painted more than 150 portraits of leading Ukrainian writers and artists; many of his subjects were later executed or sent to the Gulag and all but a dozen of these portraits were destroyed. The exhibition features his sketches for theatre costumes and three large oils, all in glowing greys, browns and silvers. The rough impasto and seemingly metallic surface of his abstract Composition (1923) anticipate the work of Anselm Kiefer. The Invalids (1924)—a group of three disabled adults and one child, portrayed realistically and with dignity—was shown to acclaim at the 1928 Venice Biennale. At the Table (1926) is more unusual. In the foreground is the back of a young woman’s head. In the background is a large radiator. Between the woman’s head and the radiator is a round metal-topped table, with a glass and a salt cellar. The painting has something of the enigmatic quality of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882).

It is barely believable that Oleksandr Bohomazov has only recently emerged from near-total oblivion

A moving catalogue article is devoted to Vasyl Yermilov, a painter, sculptor, interior designer and much else. Akinsha relates that, as a child, Yermilov “spent all his free time constructing mechanical toys from pieces of wood, and as many discarded springs and bolts as he could find lying around.” Valerian Polishchuk, whose collections of poems Yermilov illustrated, writes of post-revolutionary Kharkiv,“All the streets and houses were wild with colours, slogans, flowers and arches designed by Yermilov. The pathos of the Revolution in colours. Nothing like this had existed before and nothing, unfortunately, survived of it.” And the Red Ukraine “agitprop” train that Yermilov designed in 1920 seems to have served more as a medium for reclaiming Ukrainian folklore than for spreading Communist ideals; he himself called it a “painted wedding chest on wheels.”

Yermilov’s completed projects include the interior decoration of “The House of Defence” in Kyiv; among the unrealised projects of his later years are “A Monument to Viktor Khlebnikov” and “A Memorial Museum to Picasso,” a maquette for which is now in the Art Museum of Amherst College. Yermilov’s biographer, struck by the hoard of pieces of wood, metal, screws, nails and wires in his studio, once asked him if he “collected” material; in reply, Yermilov simply shrugged. Akinsha concludes, “For Yermilov, the best artisan among artists, these fragments were simply a natural condition of life, part of the captivating beauty of the material world.”

Both Petrytskyi and Yermilov have been known in the West for some time; Yermilov’s work was exhibited in London as early as 1975. This makes it still more surprising that their even greater contemporary, Oleksandr Bohomazov, has only recently emerged from near-total oblivion. His “cubo-futurist” charcoals and oils of modern city life, such as Tram (1914) and Locomotive (1916) are breathtakingly dynamic. The works from his two years in Armenia (1915 and 1916), though equally full of movement, employ more organic forms. Some later works are closer to German expressionism.

Bohomazov’s marriage to Wanda Monastyrska was central to every aspect of his life and work. He first proposed to Wanda in 1908. As if divining the responsibility this marriage would entail, Wanda accepted his proposal only five years later, in August 1913. This inspired Bohomazov to a burst of creativity; much of his best work dates from the next few years, and he portrayed Wanda in a variety of styles. In the relatively realistic Woman in Armchair (1914), he uses thick charcoal to suggest the sheen of her hair, her eyeliner and the sensuality of her lips. In 1914 he also completed an important treatise, The Art of Painting and the Elements, anticipating theories later expounded by Malevych and Wassily Kandinsky. The accompanying illustrations of the effects of different lines, forms, rhythms, intervals and colours are strikingly lyrical. The more cubist drawings of Wanda from these years are both research exercises and an expression of love.

Between 1917 and 1925 Bohomazov appears to have done no painting or drawing at all. This may have been because—like Malevych, Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak and several other artists and writers with at least some initial sympathy for the ideals of the Revolution—he felt deeply disorientated by its reality. Or it may have been because he was diagnosed in 1920 with tuberculosis. In any case, after returning to easel painting in 1925, he devoted most of his last two years to a single project, a large triptych titled The Sawyers. He completed the central and right-hand panels, “Sawyers at Work” and “Sharpening the Saws”, but painted only a small watercolour study in preparation for the left-hand panel, “Rolling the Logs”. The Sawyers was evidently of huge importance to Bohomazov; already severely ill, he drew more than 300 anatomically precise studies of such details as hands gripping a saw or the heels of one of the sawyers. It has been suggested that the sawyers are preparing to fashion a cross. Triptychs are associated with religious art and—according to his daughter Yaroslava—Bohomazov’s last words were “God exists, but don’t tell anyone.”

Aware that her husband’s drawings, paintings and manuscripts were by then considered anti-Soviet, Wanda kept his work hidden. Only in 1966 did two Kyiv art historians “discover” it and mount a small exhibition, attended by Wanda. Like the widows of Mikhail Bulgakov, Osip Mandelstam and Andrey Platonov, Wanda performed a heroic task. Her granddaughter, Tanya Popova, wrote in an exhibition catalogue in 2016: “I now realize what a modest life she led, on a very small pension, in a tiny room, with her husband’s work rolled up in a trunk in the corridor. That trunk seemed enormous to me when I was a child. I only learned much later what was inside. During World War II, when Kyiv was occupied, the street where my grandmother lived was part of the ‘forced eviction zone.’ She rescued my grandfather’s trunkful of priceless paintings and manuscripts by pushing them in a wheelbarrow, on foot, to Svyatoshyno, many miles away. When Kyiv was liberated, she brought everything back the same way.”

There was a long gap before the first foreign exhibition of Bohomazov’s work in 1991, in Toulouse, and another long gap before the several exhibitions put on in the last 10 years by James Butterwick, Bohomazov’s most determined champion. This silence is bewildering. In the 1910s, Bohomazov was well-known. Throughout the 1920s, he taught at the Kyiv Art Institute, joined there in 1928-30 by Malevych and Tatlin. It is puzzling that neither Exter nor Archipenko, former colleagues who enjoyed successful international careers, ever mentioned him in later years. It is still more extraordinary that Georgy Costakis, the first and greatest collector of Russian avant-garde art, appears to have been unaware of his work.

It is possible that Ukraine’s many 20th-century tragedies—the Russian Civil War, the Terror Famine, the execution in the 1930s of so many of the cultural and political elite, the Second World War, the first year of the Shoah (the Shoah by bullets)—were so overwhelming as to leave few witnesses and to intimidate outsiders from giving serious thought to the country’s recent history. A half-conscious prejudice—an assumption that all Ukrainians were mere peasants—may also have played its part.

There is at least one other surprising instance of a gifted Ukrainian public figure remaining forgotten for many years. Despite the worldwide recognition of the novel Life and Fate, it has only recently come to light that Viktor Shtrum, Vasily Grossman’s fictional nuclear physicist, is modelled on a real-life figure—Lev Shtrum, one of the founders of Soviet nuclear physics. Like Bohomazov, Lev Shtrum worked and taught in Kyiv. Born in 1890, 10 years after Bohomazov, he was executed in 1936, falsely accused of “Trotskyism”. His books and papers were removed from libraries and he was deleted from the historical record with impressive thoroughness. Only in 2012 was his theoretical work rediscovered.

There is much in this exhibition to be celebrated. Its joy and energy, however, make it still more painful to witness yet another wave of destruction sweeping the country.

“In the Eye of the Storm” is in Madrid until 30th April. It will then be in Cologne from 3rd June to 24th September