Helen said later that, like all horror stories, this one began with the smallest detail; a thing noticed that had seemed strange at the time—though you also might not have even noticed it: a small white feather on the road.

“That’s from a snow goose, isn’t it?” said Cal. He bent down to touch it, where the white edge of it, so delicate and bright, had attached itself to a chip of the tarmac. “I’ve heard of these,” he said. “My granny had a book all about geese, their habits, their seasons here… wow.”

We had all stopped. Cal knew stuff the rest of us could only listen to and learn from. His grandmother had lived here once, in this part of the north where we were, where we’d come to walk and be together. She had grown up here, when there were still some villages and crofts left, when parts of the hills were still relatively empty and you could even swim in places, in the lochs and rivers. “Sutherland used to be full of all kinds of birds,” Cal said now. “Though I couldn’t tell you for sure that that’s where this came from. It could be a bit of stuffing, I guess, from an old cushion or something…” His voice trailed off as he let his fingertip smooth down the little bit of softness around the feather’s spine. “People used to stuff things with the plumage of birds. I’ve come across that, too, in books and films…”

“I heard there were swallows,” said Katherine. “They used to come here every summer.”

“What’s a swallow?” asked Jenny.

Helen turned. “Jen!” She pretended to cuff her on the side of the head, laughed. “I know you’re joking, but you can’t be that not interested!” Then she patted Jenny’s arm as though she were a little child. “It’s why we like it here, remember?” she said to her. “So we can learn things? Get to know how it used to be?” She gestured around, the broken-up old tarmac road ahead of us, the hills on either side with their turbines like a forest of white columns stretching all the way to the horizon. “Before they put all this on it, I mean. It’s why we come here, isn’t it? To try and… understand?”

For sure, that’s what we always said was the reason for getting together three or four times a year to come north, to get to see this part of the country. Though Jenny might have been doing it more for fitness, even she was into the excitement of those journeys of ours. How it felt like an act of terrorism, of clear and focused anti-social behaviour—or rebellion, even— to drive north to one of the power stations and leave the car then, and spend the next few days camping and walking across the hills.

“No, this is something...” Cal was still kneeling on the tarmac. It was so hot. The turbines around us, their white columns, seemed to shimmer in the bright light. None of the blades were turning. The day was calm and utterly quiet, extraordinary, actually, when there’d been such winds down south in the Central Belt and we’d heard nothing but storm warnings coming from there in the days since we’d been away.

“Are you going to take it?” Helen asked. “Like a souvenir?” The little feather fixed to the spot on the road looked bright and highly present, somehow, as though it were alive. A tiny object and yet now it was all we could see.

Cal just shook his head. “I think we should leave it,” he said. “Amazing though…” He straightened up. “I hope it is from a bird, I do hope so. That will be news to tell them.” He adjusted the weight he was carrying, tightened a strap. He had the largest pack, but he didn’t mind that. It was the same on all our trips. He could manage the load because he was used to being out and walking; it was part of his PhD to go all over the country this way, tracking his own footprints. Psychogeography he called it, said it had once been a kind of philosophy.

We were all a bit in love with him, I suppose. We wanted to be near him, to do and listen to what he said and be changed by it. As David remarked once: “He only needs to say the word. It could be any word.” And he was right, we’d learn it. Any place, to go there with him and walk with him, just to understand from him what it used to be like.

We’d only stopped because Cal had seen this thing the rest of us, I reckon, would have walked right past. He said there were so many species of birds here once, before the land was taken over by the power companies. And deer and rabbits and foxes, predators, all sorts. There’d been crofts with sheep and cows, and farms. And people, people living here then, and, yes, birds.

“I don’t know much about flight patterns in detail, but I know that before all this became built over there were regular habits to animal and bird behaviour, according to weather,” he told us. By now, we’d headed up the side of a steep hill and were coming along the top. “Animals on the move, birds on the move… think about it,” Cal said. “It must have been amazing.”

We were all of us paying attention, all quiet, imagining, trying to visualise what he was talking about, animals like deer and wild birds. He had a way of expressing ideas and concepts that made you want to listen very carefully, stay near. I wished I could study with him. Write my own PhD about the north, about the days when it wasn’t what it was like now. Be someone other than who I was, I suppose, is what I was really wishing for. A someone who might know what it was to plan and imagine and react and decide. A someone else who lived in a different way.

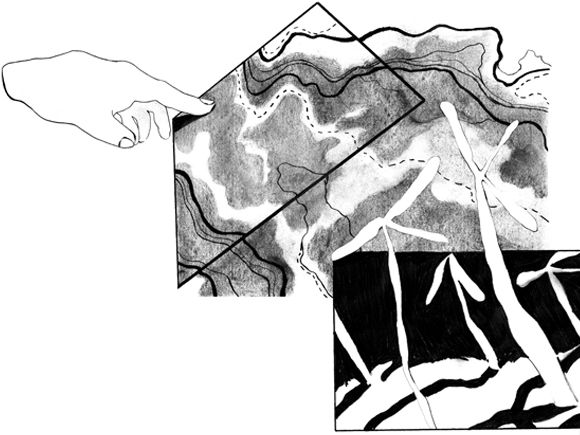

We carried on, one foot in front of another, following Cal’s special pattern of walking and barely noticing how steep it was, while he told us about one particular flight path he’d read about that took in exactly—he stopped, looked at the old paper map he always brought with him— “Yes, here,” he said. “I did read about this.” We’d all stopped. We realised the minute we did that we’d covered an enormous distance. In twenty minutes or so we’d come right up the side of that first hill. Now the road had disappeared entirely and we were nearly at the top. “Look”—he had the section of the map out in front of us, entirely flat and unruffled. Even up on the summit of the hill, the air was stock-still, like glass. Each turbine was motionless. “It’s a flight that takes in this part of the country exactly,” Cal was saying, “between these two points.” He showed Helen and Katherine the places on the map. “And, yes, the book. I remember it was a story and wild geese were in the

itle, I remember that, and it was about how people used to be, living with the land around them, and their communities. I wish I could tell you who it was by…”

He went quiet then; he might have been thinking about his family, his parents who never came up here at all even though, when his mother was a girl, she had spent every holiday with her mother in the old house before it had to be fully abandoned. There’d been a joke back in those days, he said, when people still used to come to visit up here, tourists, from all over the world. They’d drive up from the south and had been told if they wanted directions, they need only remember the old saying, “I know we can’t be there yet because I can still see the hills.” Ha ha. He told us that, down south, they used to call the country up here “Monstrous North”. For what people had let happen to the land.

He looked up and around him at the white turbine columns that were all around us and everywhere, as far as we could see. “Can you believe what it must have been like once, though?”

“Empty?” said Jenny.

“Beautiful,” said Helen.

“That was what the book was about,” Cal said. “Beauty.”

The day was moving on, we’d been walking since early morning and not thinking much about the time, but now, with the mighty stillness of thought upon us, and the clear bright peculiarity of the day—so very quiet as to have something wrong with it, almost, when there was supposed to be such wind elsewhere—time seemed held, arrested. It must have been about noon, but hard to tell in that endless sunlight cast all around us. We were tired from the steep climb, but also not tired. These walks of Cal’s were not easy, but we never minded the difficulty of an ascent, or weather; he kept everyone motivated that way. He had a leader’s method and moved us on with his talk of the past and ideas of other ways of living. Geography as psychic, as emotional. The idea of just being in a place like this, outside, open to anything that might happen and not knowing when you might go back to the Central Belt. Or that you might never return there. You might just keep walking.

Katherine would often say she had the feeling he was using us, old old friends after all, as a sort of test. How much could he ask of us that we would do? How far for him would we go?

We started up again, along the tops towards the north side of a set of low hills in the distance that gave way to a range behind, blue and lovely, though you could make out the spikes of white along the horizon. Cal had said that if we could get to that point below the line, there was an old electrics hut he knew about that we could stay in. I kept thinking about that feather, back there on the road. Its clear spine, the gentle movement of it as Cal had touched it with the tip of his finger. Look at that... As we went on, walking along the high ridge through the forest of white columns, and with each step getting higher and higher as though rising above ourselves, above even the great structures that were all around us—as though they didn’t matter and we could be free. As though we might even be part of that other world, I suppose,

is how we felt, looking back on it. That other landscape. Who might we be in it? What might our life be like then? A sort of dream?

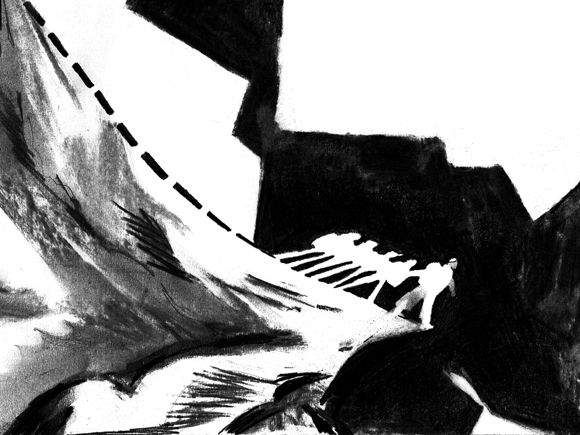

With all that we’d been talking about, thinking about, about the past and the way things had been here once, nothing could have prepared us for what was to happen next. Helen dropped to her knees—“I can’t breathe,” she said, then “Oh my god!”—and we were all looking up together—and who could have imagined it? Or known, from its appearance, how it would be? But there, coming out of the sky, a great mass was approaching. In a split second it was practically overhead and we could see it, the approach of birds, hundreds and hundreds of them, real, flying birds, coming through the turbines and fitting between them in one perfect shape, utterly unimpeded, unaffected by anything other than the great might of their own forward motion. We’d had a split second to take it in, that they were coming straight towards us, then we were surrounded by them, caught up entirely in the onward rush of their bodies and flight, the flapping of their wings and their wild cries.

We’d thought we were going to die. It was impossible to breathe, the sense of an almighty motion all around us, stifling us, and the beat of wings behind and above us, around us and in front of us… an endless flight, it seemed, of these living things, these actual flocks of birds that were upon us and around us, in front and below and behind so the air was no longer air but only beaks and claws and wings and heads and feathers and bodies, as though there was nothing else to exist in the world, as though there could be nothing else, no person, no turbine, no piece of ground nor air, only this rush of terror and horror and wonder and beauty, and heaven and hell…

And then they were gone. The sound, deafening a second ago, was already getting fainter, and the air was clearing; the great dark shadow of their presence had flooded across the sky and was dissolved into distance. It was light again. We were all of us on the ground, coughing, spluttering, hardly able to see. What was it that had happened? Was it real? They’d been birds we’d seen, actual birds alive and flying and we’d been in their midst as though we were going to be caught up by them and hurled on with them, suffocated, surrounded by them, by their sharp beaks and claws… Though we realised, too, as soon as we recovered that, apart from Cal, none us had actually felt so much as the touch of a single feather. Not a graze, not a scratch. We were all absolutely fine. Now that they were gone, it was as if nothing had happened.

Only, as Helen said, this was a horror story, remember? And an announcement had been made; the annunciation of a white feather on the road. Had it really been only that morning when we had seen it? When Cal had bent to put the tip of his finger to its fragile edge? A feather, we’d all thought then. Who would have believed it? Nothing made any sense, and yet everything did.

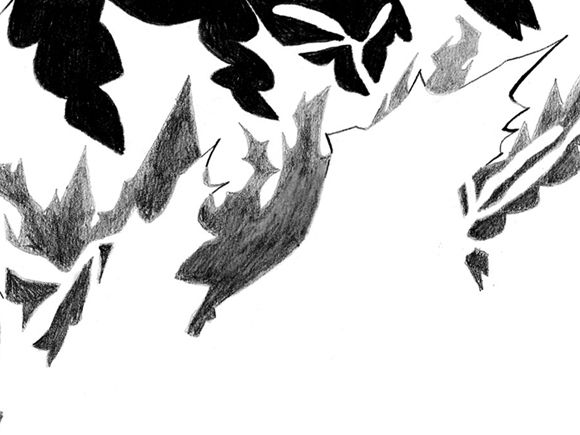

For yes, only Cal had been marked by what had happened—a thin, thin line of blood like the tracery of a single claw that ran down the length of his bare arm and fanned out along his fingers. “Just then,”words were quiet in the silence that followed the birds’ departure. “We were part of their migration.” His eyes were trained on distance, looking to where the birds had gone, to the horizon that had taken them in. It may have been that he thought he was talking to us, but really he was only speaking to himself. “Think about it…” Nothing else was apparent. Nothing else had seemed to alter. The air was empty. The sky just as blue and bright, and everything was still. Only the blades started turning then, slowly at first, in the slightest suggestion of a light breeze, and then in a gust of wind beginning fully their rotations. Part of their migration… Cal was walking away.

David called after him. “Ah, man. C’mon. Migration? What kind of a word is that?” We all of us started talking then—“What’s going on?” “What’s happening?” Behaving as though Cal was part of our conversation, as though he was still with us. Because what was that he’d said? “Migration?” Katherine asked. “Is that what you said?” “Cal?” “Cal?” But I think we’d all known, from the minute we’d seen that thin run of blood down his arm, that he was lost to us.

“What are you doing?” David started running after him. The wind was picking up, getting stronger. “What did you say?” he was shouting out to Cal. “What kind of a word?” But Cal was already far enough away that he would have never been able to hear. He was up off the side of the next hill and was walking along the top of it and then over, walking quickly, despite the wind, the changing weather, and we were all of us running by then, trying to catch up with him, shouting, “Cal!” Calling to him, wanting him to come back to us and running as though we would be able to catch up with him when he was already so far away and the wind so strong by then that we couldn’t run against it—while he was only walking on as though through it, with it, as though the wind was carrying him.

The white blades were turning faster now, and faster, as though awakened from a sleep, picking up speed and strength and whirring into life. If this was a horror story, it was a horror story only for us. The wind ricocheting across the hills, gale forces coming full at us, as still we called “Cal!” “Come on!” “Please!”—as though he might hear us when he was walking so clearly, so cleanly away that he may as well have been in another world.

Even so, we still tried to reach him, still trying, calling, in a wind so strong that in the end it was too much for us to try to follow him, to go after him, with the force of the gales only pushing us back and the turbine arms spinning at such a rate that the sound of them was terrible. So we had to turn away from him then. We ran. Back down the side of the hill and down, the wind at our backs to push us on, falling and tumbling to get back and down, down to where we’d come from, down all the way to the road, and from there to the car… Running away while all the time Cal walked on into the distance, further and further away, gone to the place where the birds were, where he could hear their wild and lovely cries… As one by one around us the turbine blades caught fire and the air began to burn.