For more than 60 years, the voice of Bob Dylan has been a thing of scrutiny and wonder. Like sand and glue, as David Bowie put it. Like a dog with his leg caught in barbed wire, as Mitch Jayne held. Spilling from the radio with that “thin, wild mercury sound”; ranging out over a heckling crowd at Manchester Free Trade Hall with a curdled, defiant “I don’t believe you…” Grown dusky and nocturnal, now, a voice steadied by the hand of eight decades.

As a lyricist, that voice was something else again: generational soothsayer, civil rights chronicler, wit, fabulist, Beat, balladeer, charged with moments of hard, keen beauty. In later years the voice seemed to find new avenues, as a poet, a writer, or hosting his satellite radio show Theme Time Radio Hour with a touch of the seasoned crate-digger, half-quoting Alexandre Dumas before playing a Wynonie Harris number.

Dylan’s latest offering is The Philosophy of Modern Song, his first book since winning the Nobel prize for literature in 2016. An examination of 66 songs, straddling the years from 1924 to 2003, it’s a work that illuminates the singer’s own career, and prompts us to consider afresh the difference between how a voice is sung, spoken or written.

The voice Dylan deploys in Philosophy is rather like that in his 2004 memoir Chronicles: Volume One—which is to say, chimerical and prone to digression. It carries echoes of the self-penned liner notes to his 1993 album World Gone Wrong—a sommelier’s guide, of a sort, for the record’s 10 rural blues covers. There is a lick, perhaps, of his 1971 experimental prose poetry collection, Tarantula, and a hint, too, of “Murder Most Foul”, his 16-minute, 56-second epic single from 2020, which referenced a grand total of 74 songs and recording artists, from “Mystery Train” to Moonlight Sonata, Patsy Cline to Thelonious Monk.

The writings in Philosophy, covering tracks from Bobby Bare to Waylon Jennings via Ray Charles and the Clash, are not critical appraisals in any traditional sense; rather, they are facts strung with impressionistic interpretation, dream sequences and doctrine, as if taking part in a late night and faintly hallucinatory version of Desert Island Discs, somewhere deep in the bayou.

Consider, for instance, his chapter on the Osborne Brothers’ 1956 track “Ruby, Are You Mad?” which encompasses a mean dose of scene-setting (“You’re sitting in the shade, slumped out, anonymous, incognito, watching everything go by, unimpressed, hard-bitten—impenetrable”); some extended speculation on the allure of “Ruby” as female archetype; winds together a few skittery stories about the Osborne Brothers and the song’s creation; lays down a couple of heady assertions (“bluegrass is the other side of heavy metal”); and sets out the track’s essential constituents, as if listed on the menu of some hip small-plate restaurant: “This song is church Latin, has plenty of backbone, and pieces of the whirlwind in it.”

It works, for the most part. Dylan has spoken (truthfully or otherwise) of how his songwriting has largely rested on the approach of playing old tunes obsessively until they become something new, and in its finest moments Philosophy can feel as if one is caught right in the gyre of this creative process. It is exhilarating.

But over an extended number of pages, the rhythms grow familiar, the clauses twitchy and each wild-eyed vision of a song competes with the last. At times, Dylan’s voice takes on the air of the professional tarot reader: “This song…” he declares repeatedly, and tells you its meaning, as if he, and only he, can interpret the mystery of the cards before us.

Among our great diviner’s stranger revelations: that Rosemary Clooney’s 1951 ditty “Come On-a My House” is in fact “the song of the deviant, the paedophile, the mass murderer”; that Ricky Nelson trumped Elvis as the true ambassador of rock ’n’ roll; and that the Who’s “My Generation” is not merely a song of the young but of “an eighty-year-old man, being wheeled around in a home for the elderly, and the nurses are getting on your nerves.” Dylan, lest we forget, is now 81. Perhaps he knows things that we don’t.

It’s worth noting that it’s impossible not to view this book as an object—its weight and girth demands it. These aren’t lengthy chapters, yet they come padded with photographs and big typefaces, each essay framed by a kitschy illustrated border so that it feels less like a collection of essays on music and more like the kind of recipe book one might receive as a gift and keep, rarely consulted, on the kitchen shelf.

It’s hard to escape the feeling that the layout distracts from the text; cheapens it, perhaps, or at least proves disorientating. One wonders whether this is—if I can steal a word from the title—the philosophy that has led to a thousand boxset reissues, to music dressed up as collector’s item and covetable artefact. The text itself cries out for another format: a slender, portable paperback perhaps; something to draw the ear back to the voice.

There are other strange calls. I am not alone in noting that only four of these 66 songs are performed by women: Nina Simone, Rosemary Clooney, Cher and Judy Garland. Nor am I the only reader to flinch at Dylan’s descriptions of women that run throughout these essays—from the “hot-blooded sex starved wench” to the “gold-digging showgirl” and a “wolf-bait on mescaline”. In a discussion of the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman”, he speaks of “the progressive woman—youthful, whimsical, and grotesque… the lips of her cunt are a steel trap.”

Elsewhere, he levers Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her” into an argument against marriage, encompassing the financial horrors of divorce, the definition of family, the benefits of prostitution, polyamory and—if one really must marry—taking an ugly woman as your bride.

One doubts that these words, as well as the general absence of women in the book, are meant as a deliberate provocation. Besides, it’s hard to argue the case for affirmative action in a collection of songs that is more about intimacy and personal insight than an attempt at a definitive list. It simply stands as a disappointment—dismaying enough to send one back to the playlists of those Theme Time Radio Hour episodes and find that they, too, stand a little light on female voices.

I’ve always liked Bob Dylan’s voice best at its sloppiest and least sermonising. The way it finds such ease and joy on Nashville Skyline, or gathers into something exquisitely incantatory on “Key West”, the track that closed out 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways. Most of all, I like it on “I’ll Keep It with Mine”, the song he wrote in the early 1960s for Judy Collins and that he attempted to play himself during the Blonde on Blonde sessions; but my favourite version is an early studio outtake, sounding for all the world as if he’s sitting there at the piano, making it up on the spot.

The lyrics for “I’ll Keep It with Mine” are set out on Dylan’s website. If you seek them out today, they don’t make for very much—it’s a song of friendship, an offer to help lighten the load, with a neat little verse about a weary conductor stuck on the line. But when sung aloud, it somehow draws flame.

The failure or insubstantiality of the written word is a subject that Dylan returns to often

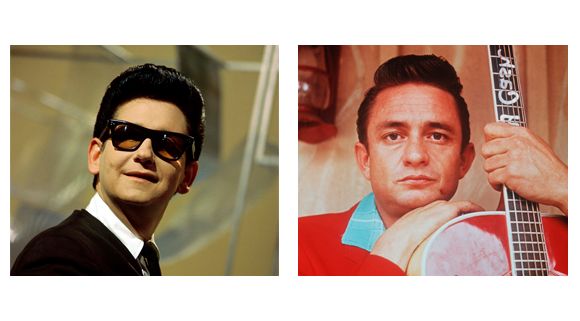

I looked for that voice a great deal in this book, something to break up some of the more runic visions and theorising. It’s perhaps not surprising that it rang out most clearly in the short chapter on Johnny Cash’s “Big River”. Cash was, of course, Dylan’s great encourager on Nashville Skyline, and his duet partner on its opening track, “Girl From the North Country”, in an era when Dylan’s songwriting found the straight-gazed simplicity that would also lead to “I’ll Keep It with Mine”.

The chapter sings that way, too. There is something square and true about the way that he talks about the construction of this song—the “chain-gang thump” of its acoustic rhythm guitar, the gospel influence, the line back to Woody Guthrie. And it’s there, too, in the tender way he fêtes Cash, as man, singer and friend: “He could climb across rivers... He could lay down greenhorns.”

He strikes a similar note in his appraisal of John Trudell’s “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore”. There’s a simplicity to the chosen track—a poem really, read live. It stands alone but, as Dylan explains, acquires extra weight when one understands the tragedy of Trudell’s own life: a Native American whose pregnant wife, three children and mother-in-law were burned to death in an arson attack on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation in 1979.

The spareness of the song, the plain horror of the story, means that in this chapter Dylan avoids whirling too far into the phantasmagoric, encouraging instead further investigation of Trudell’s catalogue and ruminating upon the song of the sufferer. “In this song there’s a million ways to go mad, and you’re familiar with them all,” he writes, “you just don’t talk about it and even if you did, your words would be difficult to catch.”

The failure or insubstantiality of the written word is a subject that Dylan returns to often on these pages. At moments, he seems to concede the possible futility of the task before him. The challenge of writing about music at all, of describing not just how a song works and what happens in the arc of its lyrics but also just how the damned thing makes you (and perhaps other people) feel.

All the same, Dylan can be electrifying in his attempts. His take on Sonny Burgess’s “Feel So Good”, for instance, brings a long mesmeric passage on the experience of being in the sweet flow of life: “you’re intensely alive, coming through the kitchen, and you’re rockin’ narrow and hard…”

At other moments, the prose purples and grows unwieldy, or reaches too readily for others’ turns of phrase—something Dylan does often, we know, but here it’s a habit that compromises the emotional truth of his writing.

Sometimes he just plain gives up. In his closing chapter, on Dion & The Belmonts’s “Where or When”, he speaks of how when “Dion’s voice bursts through for a solo moment on the bridge, it captures that moment of shimmering persistence of memory in a way the printed word can only hint at.” I’m not sure that’s entirely true. The finest music writing finds a melody of its own to convey such moments of shimmering persistence. More illuminating, perhaps, is a passage on Roy Orbison’s “Blue Bayou”, in which Dylan notes how “songs can be slippery in the studio—they can go right through your fingers. Some of our favourite records are mediocre songs at best, that somehow came alive when the tape was running.”

Some of the writing here in The Philosophy of Modern Song is mediocre. It is problematic, and repetitive and sermonising, and the art direction is questionable. But each line is charged by the fact that this is Bob Dylan, that voice of sand and glue, dog leg and barbed wire. That in the right moment, to the right ear, these words could sound like thin, wild mercury. One can’t help but wonder how it might come alive when the tape is running.