The damaged Khalid ibn Walid mosque looks over the destroyed city of Homs ©Robert Perry/TSPL/Camera Press

The Battle for Home: The Memoir of a Syrian Architect by Marwa al-Sabouni, Thames & Hudson, £16.95

Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila al-Shami, Pluto Press, £14.99

For years the news from Syria has not been good. In January 2011, a national uprising began after a Syrian man set himself alight in imitation of the Tunisian fruit-seller who had sparked the Arab Spring six weeks earlier. In February, protests against police brutality spread to the capital Damascus. Initially peaceful and with limited objectives—prisoner releases, repeal of the emergency law, multiparty elections—the protesters were faced with deadly attacks from Bashar al-Assad’s security forces. Gradually the revolt turned into an armed revolution, which aimed to overthrow the Baathist state. Within two years the country was engulfed in a civil war, infected by jihadis both domestic and foreign.

Syria has experienced every imaginable catastrophe—from chemical attacks to the tentacular spread of Islamic State (IS). According to a recent estimate, 470,000 people have died in the conflict while 10 million are now refugees. In addition, the country’s physical environment has taken a battering. Ancient monuments have been destroyed: IS blew up the Temple of Bel in Palmyra and, during fighting between the government and rebels in Aleppo, the 1,000-year-old minaret of the Umayyad mosque collapsed. Cities have been flattened; homes destroyed.

On 27th February, a shaky ceasefire was agreed between most of the warring parties that has allowed civilians a measure of respite. Geneva III is supposed to lay the groundwork for a permanent settlement—possibly involving the division of the country—but while that prospect is still distant, Syrians are starting to think hard about how, when the time comes, they might rebuild their country. The destruction might be tragic, but it does allow for the possibility of creative reconstruction.

The Syrian architect Marwa al-Sabouni’s memoir, The Battle for Home, is an intelligent and cool-headed contribution to this new movement. That al-Sabouni managed to write the book at all is something of a miracle. She has lived in Homs, Syria’s third largest city, throughout the war. In that time, she has witnessed the bloody aftermath of bombings from her window, and been forced to dodge mortars and snipers on her way to meeting her PhD supervisor. Even so, her intellectual explorations never faltered. In 2013 she emailed the philosopher Roger Scruton with a list of questions about his 1981 book The Aesthetics of Architecture. Scruton—who in his foreword to her memoir describes her as a “profound thinker”—says they discussed the ways in which buildings and the lived environment reflect a society’s health, and what architects can do to improve the lives of ordinary people.

Homs, like many Syrian cities, was developed with little concern for its inhabitants. In the 1960s, factories and refineries were built in urban areas, transforming the city’s once famously clean air into a dust-filled, noxious nightmare. The historic Old City was either neglected or thoughtlessly repaired: “Random and tasteless additions disgraced it everywhere,” al-Sabouni writes. “Parts of the centuries-old buildings were left crumbling; some stone houses had been removed altogether to be replaced by four or five-storey concrete blocks.” Growing up in the 1990s, al-Sabouni found there were no functional parks, public cultural centres or—apart from the Old Souq—any shared spaces where people of different classes and religions could mingle on neutral territory. Like other young people, she felt “jailed behind the bars of nothingness.”

The poor town planning was not only the result of aesthetic blindness: hubris and greed also played a part. One governor was desperate for Homs to be more like Dubai—described here witheringly as looking “less like a city and more like a shelf of perfume bottles”—and he encouraged shoddy high-rise buildings to sprout all over the city. “It was painful,” al-Sabouni writes, “to witness those pin-like protrusions randomly puncturing the city, like cigarette burn marks on a tortured body.” Her violent simile is deliberate. Al-Sabouni believes you can link Homs’s unhealthy and alienating environment with the hatred that erupted during the revolution. “Architecture offers a mirror to a community,” she argues, “and in that mirror we can see what is wrong and also find hints as to how to put it right.”

As an undergraduate before the war, al-Sabouni’s teachers told her to copy western styles—American homes from Cape Cod or New England, chosen from “random library books” that had little in common with Syrian traditions or ways of living. The city’s Ottoman architecture was regarded as old fashioned and uninteresting. Only once the civil war started did al-Sabouni dig deeper into Homs’s heritage, seeing its ancient buildings as a model for harmonious co-existence. In Old Homs, for example, the mosque of Khalid ibn Walid (an early Muslim general) and the Holy Church of St Mary (the original structure dates from 59AD in what was then called Emesa) are positioned close by one another. The call to prayer and church bells commonly overlapped. Judged on purely aesthetic criteria, says al-Sabouni, there isn’t much to either building. Nevertheless, she adds, they served an important function: “Their coarse textured façades, moderate heights and low wide door welcomed every visitor humbly into their warm and simple interiors, and for that reason they were loved, becoming—in their own way—instruments of reconciliation between communities.” Both have been severely damaged during the war.

"It was painful to witness those pin-like protrusions randomly puncturing the city, like cigarette burn marks on a tortured body"Though al-Sabouni values traditional Islamic architecture, she has little time for the oriental clichés that dominate modern Arab buildings. Asked by her teachers to design a trade centre in Damascus, she was downgraded for not including any “Islamic” elements—domes, minarets or mashrabiya (an oriel latticework window). These features make up the kitsch language favoured by Arab rulers that has little consideration for their original context. Historically, al-Sabouni says, such notionally Islamic elements were actually “a decorative by-product of the architectural process,” rather than something that carried “a separate goal or loaded agenda.”

Although al-Sabouni is careful not to draw explicit political conclusions from her aesthetic theories—she lives precariously between a dictatorial regime and Islamist rebels of varying degrees of fanaticism—it is not hard for the reader to connect the dots. The western styles her teachers preferred have their corollary in the Baathist state’s ersatz modernisation, where superficial symbols of success—the Cape Cod holiday home—were admired but no account taken of the open societies that allowed such forms to flourish. Likewise, the transformation of the Islamic dome from a natural result of a mosque’s design to an imperious marker of cultural identity mirrors what has happened to religion in the Middle East. Syrian Islamists want to impose political Islam on a diverse society, just as the bad architect plonks a dome on a bank or public building to make it appear more authentic.

So how could Homs be rebuilt? Al-Sabouni began to formulate her ideas in 2012 when she was finally allowed to return to the devastated Old City, where she and her husband ran an architecture office. She describes the scene vividly: “People walked side by side, electrifying the atmosphere with their conflicted feelings: caution, amazement, hatred, blame, triumph, relief, sadness, heartache.” Amid the debris, she confesses to feeling “the most powerful curiosity.” She “wanted to have the freedom to contemplate this massive strangeness: to paint it, picture it, film it, to fully absorb it, but this was out of the question in such a delicate situation.” Instead she thought about how her home city could be rebuilt.

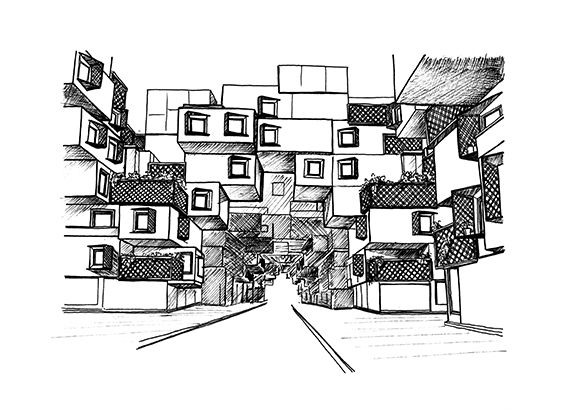

The place she chose to redesign was not the complicated Old City, but Baba Amr, an outer district of Homs where her husband was born. Official plans for remaking the area had the typical unimaginative panoply of high-rise buildings and long boulevards, with the main mosque flanked by two domineering metal structures. In contrast, al-Sabouni’s design has the mosque

organically integrated into an urban area with a park, library and sports centre. Not only is her design a more natural way of organising space, but it also means that the religious character of Baba Amr would be healthily absorbed into the environment, to help prevent “its residents degenerating into the kind of identity fanaticism that we had already seen.” Instead of tower blocks, she suggests modestly sized “Tree units”: mixed spaces with shops and living quarters side by side. Her drawing shows the Tree units clustering over a street and “holding hands” in the middle, echoing the bridges that run across the narrow alleys of the Old City.

After perfunctory consideration, the authorities rejected her plans. Although their practicality and expense can be questioned, it is true that while there is nothing approaching official democracy in Syria, original or unusual thinking will be discouraged. She looks with envious admiration at the public spirit of European democracies, “that enables people to take charge of their situation, to put pressure on governments, to start initiatives of their own.”

"We are witnessing a revolution in social values that will be impossible to turn back even if Assad strikes a deal with the rebels"Taking charge of their own lives was the dream of Syria’s peaceful protestors back in 2011. Their often neglected story is told with moving detail in Burning Country, by the Syrian-British novelist Robin Yassin-Kassab and the human rights campaigner Leila al-Shami. In the first years of the revolution, many towns and cities that had successfully banished Assad’s army began to experiment with representative democracy. Yabroud, 80km north of Damascus, set up an elected council that ran public services including schools and hospitals. Such councils were not perfect: some were plagued by tribalism and authoritarianism; female representation was poor. Some have been closed down by Islamists who set up rival sharia courts or were retaken by the regime in places such as Homs. But many still function and no matter how messy, they offered the first chance in 40 years for Syrians to have some say over how they were governed—to breathe the fresh air of freedom that has been stifled for so long. During the current ceasefire, Syrians in non-government areas have taken the chance to demonstrate with the revolutionary flag, their enthusiasm for liberation seemingly undimmed by the bloodshed.

One such place whose fame has spread through social media is the previously little-known town of Kafranbel. Every Friday, protestors put up witty signs in Arabic and English, often riffing on popular culture. One week they had a parody film poster of Gone with the Wind with Vladimir Putin and Assad locked in a romantic clinch à la Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. Another showed Assad as a contestant on America’s Got Talent (renamed Terrorist’s Got Talent), bringing a dead child onstage to the approval of the judges—Iran, Russia and the world. There is also the Top Goon online puppet show, a kind of Syrian Spitting Image, which parodies stock villains like the secret police. The bitter humour humanises Syria’s civilians, so often regarded as either deranged persecutors or passive victims.

There has also been an artistic flowering amid the rubble. Syrian-born artist Tammam Azzam’s wistful image of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss superimposed on a burnt-out building is one of the most hauntingly memorable. But there are also rap groups (continuing the thriving Palestinian-Syrian rap scene from before the war) and heavy metal groups such as Anarchadia. In liberated areas especially, freethinking and atheism are more openly expressed and women are taking a more active role in running services as men go out to fight. We are witnessing a revolution in social values that will be impossible to turn back even if Assad strikes a deal with the rebel groups.

When al-Sabouni’s friends tell her they want to turn the clock back to before 2011, she says she is puzzled. “Why would anyone support a process of massive change, then simply—and very late in the day—regret the destructive repercussions and want things to go back to the way they were?” Syria, like the rest of the Middle East, cannot turn back. Too much has happened; too many lives have been lost; too many assumptions challenged. “Putting Syria back together is what I am trying, in my imagination, to do,” writes al-Sabouni. Her plans will remain on the drawing board—for now.