Sixty years ago this summer, in the shadow of Suez, the age of Aldermaston and the retreat from empire, the British media found itself fixated on anger. The curious thing about this anger was that it appeared to lurk not in such age-old repositories of discontent as the politician or the trades union activist, but in the much less likely figure of the author. It was the year in which the literary collective known as the “Angry Young Men” took up residence in comment pages and on television screens, when up-and-coming writers like Kingsley Amis, John Osborne and Colin Wilson lit up the review sections like traffic lights, and when a minor scuffle between two dramatists could make the front page of the Evening Standard. More significantly, it was the year in which the “new” anger was thought to have moved on from its original grounding among a gang of middle-class malcontents—Amis was after all by then a university lecturer—and assumed a defiantly working-class focus.

Or perhaps it was only reverting to type. Working-class literary anger, after all, is as old as working-class fiction. Robert Tressell’s great exposé of the Edwardian painting and decorating trade, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists (1914) is aflame with it. The Depression-era novels of Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Harold Heslop and Walter Brierley, author of the classic Means-Test Man (1935), blaze with dissatisfaction at a political and economic system that had put three million on the dole and reduced the industrial north to the silent wilderness of Heslop’s Last Cage Down (1935).

In our post-crash world of austerity and limping Tory governments, you might expect the fiction of the present decade to be full of modern-day Brierleys and Gibbons. That it manifestly isn’t has several explanations, but one of the most revealing lies in the nature of that post-war anger and the backgrounds of the writers supposed to be expressing it.

The great symbol of post-war fiction’s working-class resentment was John Braine’s novel Room at the Top (1957). This no-nonsense account of Joe Lampton’s steady climb from nowhere to commercial and social triumph struck a chord with the reading public. Twelve thousand copies of the book were said to have been sold in the week after Braine appeared on the BBC’s Panorama. Once details of the highly promotable author’s early life began to leach into the magazine profiles, the ex-librarian from Bingley found himself hailed as “the new apostle of success.” Humbly born, cynical and aspirational, Lampton—widely assumed to be a projection of his creator—was clearly a man whose time had come.

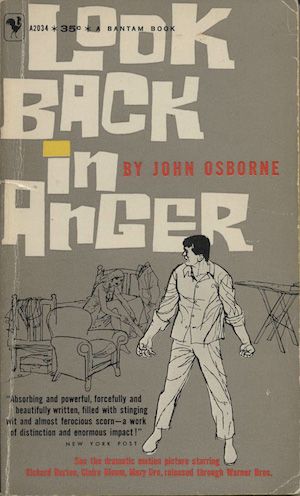

The idea of the “Angry Young Man”—there were a few “Angry Young Women” at the margins—was not, by this stage in its existence, remotely newfangled. First used as the title of an autobiography by the Christian writer Leslie Paul as far back as 1951, the phrase acquired lasting public significance when the press officer of the Royal Court Theatre, asked by a journalist what he thought of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (1956), contended that its author was “a very angry young man.” Thereafter, sensation-hungry columnists who remembered the controversies that had attended the early work of Amis, Wilson and John Wain, hastened to assemble these very disparate talents into a full-blown movement, picking up those who were neither young, male or angry along the way. Iris Murdoch became an associate member on the strength of her first novel Under the Net (1954). So, even less plausibly, did the 39-year-old adult education lecturer Richard Hoggart, in the wake of The Uses of Literacy (1957), a sober exercise in literary sociology.

If the “Angry Young Men” were an artificial construct, an invention of journalists to rank with the “Bright Young People” of 30 years before, then what were their members angry about? This was a question which contemporary commentators struggled to answer. Class conflict, the atom bomb and “the Establishment” came and went, together with what the critic Anthony Hartley called “the limited revolt of the intellectuals” against the blanket of the post-war welfare state. Certainly, there were occasional outbreaks of genuine ideological fury—Osborne’s 1957 essay “They Call it Cricket” sets about, in no particular order, the Church, the newspapers and the Royal Family (“the gold filling in a mouthful of decay”). On the other hand, the distinguishing mark of 1950s anger is a resentment that seems, in the end, personal rather than political.

Amis’s Lucky Jim (1954), for example, contains a brisk exchange between Jim Dixon and his bête noire Bertrand Welch on the need for redistribution of income, but Amis’s real quarrel with post-war social institutions is that they don’t offer a more prominent place on their upper floors for Amis himself. Scratch the 1950s’ finest, and all you find is a meritocrat narrowly concerned with personal advancement. Lucky Jim ends like a novel by Henry Fielding or Tobias Smollett, with its hero walking off into the sunset with a well-paid sinecure and a pretty girl on his arm. Braine’s ambitions, too, were almost entirely focused on material success. He is supposed to have told Amis that his dream of real triumph was a procession through his native Bradford with himself at the head flanked by a pair of naked women drapedin jewels.

It can hardly be a coincidence that both men drifted steadily rightwards—Braine in particular transformed himself from a card-carrying nuclear disarmer into a Conservative so extreme that even the Thatcher-supporting Amis was sometimes reluctant to be allied with him. And yet the same fundamental lack of solidarity can be found in the 1950s writers tagged with the label “working class.” To read the proletarian classics of 60 years ago is to be struck by quite how fractured were some of the demographics on display.

From Philip Callow’s Lawrence-reading Bohemians to Stan Barstow’s upwardly-mobile draughtsmen and office-workers and Jack Trevor Story’s skirt-chasing door-to-door salesmen, the effect is not of a single, homogenous landscape but a series of contending social units, each with its own ambitions and loyalties—or lack of them. Even Alan Sillitoe’s Arthur Seaton, from Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958), perhaps the most authentically downmarket of the decade’s working-class heroes, is simply a surly individualist to whom the struggles of the proletariat and the rise of the Labour movement are mostly irrelevant. As the cockney boy in Doris Lessing’s Retreat to Innocence (1956) ominously puts it: “I’ve been raised on William Morris and Keir Hardie and all that lot and I wouldn’t say a word against them…But I says to my dad, I says, what’s in for me?”

What has happened to literary anger in the six decades since John Osborne? And what happened to its working-class variant? Naturally, there are plenty of writers, male and female, who continue to be wheeled into the public gaze with the word “angry” bristling from their jacket copy. I myself, many years ago, was proud to be described by the Guardian as “angry and energetic.” But, as in the 1950s, anger is always difficult to pin down, always likely to be muddied by half-a-dozen other factors.

Much of the book-world anger of the 1970s, for example, came from right-wing writers of the Amis-Larkin school, who disliked the Wilson governments, what they imagined to be the robber barons of trades unionism and the 1960s, which they regarded as the fount of all modern social evil. One remembers Larkin’s (mercifully unpublished at the time) lines addressed to the Queen on the Silver Jubilee of 1977:

After Healey’s trading figures

After Wilson’s squalid crew

And the rising tide of niggers

What a treat to look at you!

From the other side of the political divide, Thatcher and Thatcherism were natural targets for the anger of the following decade. Yet revisited 30 years later many of the celebrated put-downs of the grocer’s daughter by Salman Rushdie (“nanny Britain, strait-laced Victorian Values Britain, thin-lipped, jingoist Britain is in charge,” for example) or Angela Carter (who once complained that Thatcher “coos like a dove, hisses like a serpent, bays like a hound”) seem not so much angry as petulant, the product of onlookers whose antipathy not only tended to blind them to the roots of her appeal but turned their insults into something close to snobbishness.

The same structural flaws regularly attend the anti-Thatcher novel, whose vicious, self-seeking, duplicitous anti-heroes can be detected on the lower slopes of British fiction from about 1983 onwards—see Julian Rathbone’s Nasty, Very (1984), Terence Blacker’s Fixx or David Caute’s Veronica, Or The Two Nations (both 1989). Picaresque, upwardly mobile, heartless to a fault, Thatcher-man’s negative vitality very often works against the aesthetic temper of the novels in which he features, for its ultimate effect is to confuse the moral landscape in which he is supposed to be operating: what is intended as satire often comes close to glorifying what it is bent on disparaging.

The anger that critics strove to detect in the writers of the 1950s is even more meaningless in an age where most writers slough off their class affiliations by the simple act of picking up a pen. Zadie Smith grew up on a north London council estate, but it would take a bold taxonomic stroke to mark her down as a working-class writer in the mould of, say, Walter Greenwood or James Hanley. And if the landscapes of the old working-class novel were so variegated as to disbar very much in the way of group consciousness or collective ideology, then the boundaries of their modern equivalents are wider still.

Not, of course, that this has stopped anger making its presence felt. At any time in the past 30 years a small band of novelists has been hard at work bringing back despatches from the margins of British society—the council estate bohemians of Carol Birch’s early work, the dispossessed northern women of Livi Michael’s Under a Thin Moon (1992), Niall Griffiths’ drug-addled vagrants or a novel like Anthony Cartwright’s Iron Towns (2016)—but their findings often seem less concerned with class discontents than with a series of different classes, united only by their detachment from the mainstream. With the exception of James Kelman, an old-style Scottish leftie, who continues to believe that the English language is an instrument of imperial oppression, working-class ideologues are in very short supply.

But perhaps the greatest impediment to literary anger in the modern age is professional. The writers of the age of Osborne and Braine may have been lumped into a series of phantom “movements”; their well-publicised resentments may only have stemmed from the conviction that the world owed them an income; but to set against these disabilities was the fact that the literary world in those days allowed them a degree of autonomy. By contrast, the financial pressures on literature in 2017 are such that most writers are forced to spend large parts of their time on activities only indirectly concerned with writing.

The specimen contemporary novelist tends to work in a university creative writing department or another form of teaching. None of this actively anaesthetises him or her from being a transformative force; but the disabling effects of this institutionalising can be seen throughout modern British literature. It was noticeable, for example, how rapidly the torrent of anger produced by last year’s Brexit vote reduced itself to a kind of peevishness—the low-level irritation of a profession for whom genuine expressions of annoyance are nearly always secondary to a much more fundamental urge: the need to earn a living.