The Los Angeles poodle rock circuit was a pretty crowded scene back in the late 1980s. Bands like Poison and Mötley Crüe—yes, those are umlauts—were wowing the LA crowds with their tight trousers and squealing guitars, spending almost as much money on hairspray as on drink. But one band went on to eclipse them all, releasing a debut record 30 years ago so breathtaking, so extraordinary and so brilliantly sordid that, at a stroke, it made the others look pale by comparison.

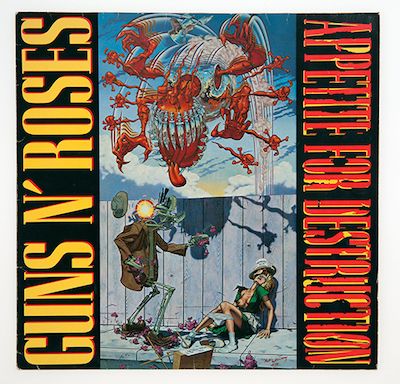

That band’s name was Guns N’ Roses and the record they made was Appetite for Destruction, a colossal blastwave of rock’n’roll that seemed to wake the world from its mid-80s, Huey Lewis-induced torpor. Threatening, seedy and very rude, it was everything that teenage boys wanted out of music. The guitars were loud, the drums were loud, the whole thing was deafening, brash and overdone. What’s more, the album was jam-packed with catchy pop hits. “Sweet Child o’ Mine” went to number one in the United States and across the globe. The football-terrace chant of “Paradise City” became something approaching a rock anthem. To celebrate its 30th birthday, the band has emerged from retirement to go on a world tour.

Appetite for Destruction sold 30m copies and made the band superstars: Axl Rose, vocals; Slash, lead guitar; Duff McKagan, bass; Izzy Stradlin, rhythm guitar; and Steven Adler, drums—the five boys had made a world-beating album of unaffected, straight-faced rock.

And no one else would ever do it again. If we date the start of rock’n’roll with Elvis’s Jailhouse Rock in 1957, Appetite for Destruction arrived exactly halfway between then and now. And it was the last great rock’n’roll album to dominate popular culture. In the decades since, other bands went on to play loud guitars and make era-defining records, but all of them—from the Stone Roses to the White Stripes—made music that was subtly influenced by styles other than rock. Even the likes of Oasis had a sentimental side. Appetite for Destruction had none of that. It was an exercise in total directness. The music, the lyrics and the character of the sound held no ambiguities—the entire record was what you might call a single entendre: it was all on the surface, up-front and screamed into the listener’s face. When you recall that before Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis, rock’n’roll was a euphemism for sex, you are reminded of the form’s unvarnished origins. Nothing since has come close to matching the purity of the rock that Guns N’ Roses achieved in the 12 tracks they unleashed in 1987. If you’re not sure what that “purity” consists of, the opening lyrics of “Nightrain” should make things pretty clear:

Well I’m a West Coast struttin’

One fat mother,

Got a rattlesnake suitcase under my arm,

Said I’m a mean machine,

I’m drinkin’ gasoline, And honey you can make my motor run…

Bands don’t write lyrics like that anymore. If anyone tried, people would assume they were joking, deluded, or some sort of novelty act. Which leaves Appetite for Destruction standing alone, a granite-hard monument to all-out rock’n’roll, the genre that it both embodied and brought to an end in 53 minutes of outright brilliance.

Its power remains undimmed. The album starts with “Welcome to the Jungle.” The intro is a stupefyingly exciting morass of delaying guitars and fizzing cymbals and then, above it all, a sound like a tornado howling through a ruined building. Or is it an air-raid siren? Or maybe an industrial sander? No, it’s Axl Rose, making a noise like a troupe of asthmatic wolves, yowling together in one hideous chorus. There’s something indefinably suggestive about Axl’s witchy voice, something percussive and propulsive, horrific and weirdly hypnotic.

We are the people that will find,

Whatever you may need,

And if you got the money, honey,

We got your disease

In the jungle,

Welcome to the jungle... Won’t you feel my—my—my—my serpentine?

Filthy.

And then there’s Slash, wearing cowboy boots and a top hat—yes, that kind of top hat—and a Gibson Les Paul guitar slung about his waist. It was Slash, born Saul Hudson in Hampstead and raised in Stoke-on-Trent—yes, that Stoke-on-Trent—who played the monstrous riffs, who, along with Axl, wrote many of the album’s best songs and who created the immortal intro to “Sweet Child o’ Mine.” But despite his absent gaze Slash was one of the most gifted popular musicians of his generation, capable of producing solos to compete with anything by jazz guitarists Wes Montgomery or Charlie Christian for technical complexity and verve. It’s the dense texture of Slash’s guitar playing that gives the album its cyclonic intensity, that makes it sound so damned wild.

"There was no introspection. They weren't worried about appearing crass—the album's attitude towards women is awful"It is hard to overstate the effect that Appetite for Destruction had on the adolescent audience of the late 1980s. When the video for “Welcome to the Jungle” was first shown on MTV—at 5am one Sunday morning—the station’s switchboard was jammed with calls from viewers who wanted to see it again. It became the channel’s most requested video. And where MTV led, the world followed—everyone went GnR mad. Boys wanted to be like them and girls fancied them rotten—Axl, in particular. The album’s grand finale, “Rocket Queen,” actually features the sound of Axl having sex with a groupie in the studio’s recording booth. The unmistakable noises appear loudly in the background of what is without doubt one of the sleaziest pieces of music ever recorded.

And after you’ve released an album with a recording of you doing that on it, where do you go from there?

A world tour as it turns out, and from there, onwards to global adulation. Then came the hodge-podge album Lies (1988) followed by more touring, and then in 1991 the by turns brilliant and slightly idiotic Use Your Illusion, the descent into self-indulgence signalled by the fact that it came in two parts. It didn’t get close to the feverish brilliance of Appetite for Destruction, yielding instead schmaltzy rock ballads like “November Rain,” the video for which is unintentionally hilarious. Then came the drink and drugs, another global tour, a period of turmoil, another album called The Spaghetti Incident? (don’t bother) and then the inevitable split.

Appetite for Destruction caused a huge rumpus, but it left no real legacy. By the 1990s, it turned out that people wanted hip-hop and techno, and if they needed loud guitars it was to the new sound of grunge that they turned—especially to Nirvana—with all its ambiguities and self-doubt. Or Britpop with all its irony and quirkiness. Against all that, the brash men with the tight trousers and the big hair looked a little bit out of date. And really, they had been out of date all along. Appetite for Destruction never really belonged in the post-modern era of the 1980s. There was no knowing wink, or self-referential humour to any of it. GnR didn’t say anything political or about society. There was no introspection. They weren’t worried about appearing crass or sexist (the album’s attitude towards women is hair-raisingly awful.) And despite its punk inflections, there’s no evidence of irony when in “My Michelle,” Axl shrieks:

Your daddy works in porno,

Now that mommy’s not around,

She used to love her heroin,

But now she’s underground.

Appetite for Destruction was a glorious romp, a piece of virtuoso brilliance. If the record had any sort of message, it was simply that booze, sex and rock’n’roll were damned good fun and it’s pretty hard to quibble with that. But Guns N’ Roses projected this hedonistic message into a country and a world that was changing fast.

In August 1987, three weeks after the album was released, Ronald Reagan appointed Alan Greenspan to the Chairmanship of the Federal Reserve board. The most triumphalist chapter of Reaganomics had begun, a process that would fundamentally reshape US society, and in which Wall Street would boom, while other sections of society were left to fend for themselves. America was seared with division, and this was reflected in the music of the period. In 1988, the LA-based hip-hop outfit NWA released Straight Outta Compton, an indictment of America’s racially segregated inner cities which, though it made for tough listening, offered a much clearer indication of where popular music was heading than Appetite for Destruction.

Straight-up rock’n’roll had no place in that nascent neoliberal world. Guns N’ Roses managed to elbow their way into the popular consciousness, but really it was all like a dream of the good times: of a “Paradise City, where the grass is green and the girls are pretty”—a vista that Kubla Khan might have recognised, a solipsistic vision in which the real world was nowhere to be seen.

Appetite for Destruction was the final word on rock’n’roll and it brought the curtain down in dazzling style. It was a record that was out of its time, which was a shame in a way. But being out of your time has its benefits. For one thing, it makes you timeless—and immortality is pretty hard to beat.

Additional photo credits: Eyebrowz/Alamy Stock Photo, Larry Marano/Getty Images, Marc S Canter, Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, The Stewart Bonney Agency/Rex/Shutterstock