Science fiction is a genre doomed to profundity, unable to avoid banging its head or stubbing its toes against philosophical dilemmas as it goes about telling its stories. Though it doesn’t seem likely that well-thumbed copies of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness show up on the sets of many space operas, existentialism is always likely to put in an appearance when the theme is our aloneness in the universe or else the encounter, feared and desired, with otherness and the alien. Being alone in the universe and not being alone in the universe —two inexhaustible subjects.

A pair of recent American films, neither masterpieces but full of enjoyable elements, highlight these themes. In Passengers Jim Preston (Chris Pratt), an engineer travelling in suspended animation and one of thousands of people heading for a colonised planet, is woken nearly a century ahead of schedule. In the first third of the film, its most successful part, he learns that to be the only wakeful person in a world of sleepers is a living nightmare. This is solitude in its paradoxical modern form, full of empty interaction. When he wakes up, a smiling hologram leans over him with reassurance. Then he receives an upbeat briefing from a simulated speaker addressing a whole room full of passengers, unaware that she has an audience of one. When Jim tries to point this out, she sweetly raises a phantom finger and asks for questions to be left until the end.

In Passengers the engine of the spaceship Avalon is silent as it heads towards the colony planet. How quiet is deep space? Quiet seems the wrong word to denote the impossibility of sound. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (1968) is one of the few films set outside the Earth’s atmosphere to respect its silence on the soundtrack. (Even Alien, despite the famous tagline of “In space no one can hear you scream,” made sure the throb of the Nostromo’s engines was audible from the first sequence.) Already those sounds tell us that the reality of nothingness has been blotted out—perhaps because a deep sound gives a powerful cue to our visual imagination, making it less likely that we will see the special effects in front of us as unreal.

2001 had the vision to predict a future that was one part cosmic awe to a thousand parts of stultified travel, but underestimated our compulsive need for distraction while we wait to arrive wherever it is that we’re going. The voyage of the spaceship towards a rendezvous with the alien monolith beyond Jupiter is still astonishing, but some of that astonishment is down to the iPod not having been invented when it was made. So far from home and not a playlist to be had! No wonder Bowman (Keir Dullea) looks so glum.

The writer and director of Passengers (Jon Spaihts, Morten Tyldum) understand that nowadays we don’t take our solitude neat. We dilute it constantly. Jim can whip digitised spectators into frantic applause with the excellence of his basketball. He can make stunning progress in dance-offs with a programmed opponent. It’s just that he is robbed of the company who would witness, and give value to, either victory or defeat. Without other people there is nothing. There isn’t even loss.

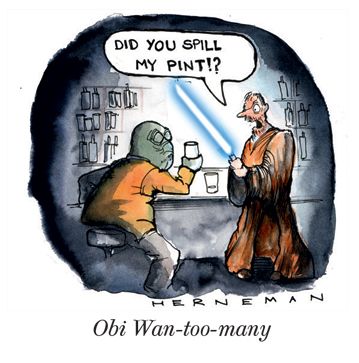

When Jim comes across a working bar aboard the Avalon, whose android bartender is programmed to engage convincingly in hostelry-level banter and philosophising, the audience is cued to pick up an echo from a rather different Kubrick film: the sinister bartender Grady (played by Philip Stone) in The Shining, suavely inciting the hero to murder. The unsettling android in Passengers is played by Michael Sheen, a good fit for an actor who is hard to cast, with his sly sparkle and clever ferrety face.

Jim gazes into the hibernation pod of attractive journalist Aurora Lane—a name that could hardly be more hopeful if it was Dawn Future. Watching her lying there in her glass casket like a fairy-tale princess, does he think, “Sartre got it wrong—hell isn’t other people, it’s not having other people”? No, but it’s a fair paraphrase of his state of mind. And will he wake this Sleeping Beauty, whether with a kiss or an instruction manual and a screwdriver? Jennifer Lawrence’s name and face are on the posters, which certainly shortens the odds of an awakening.

Some films in which our species comes across other intelligences—Independence Day (1996; rebooted in 2016) is an obvious example—have no interest in the Other, treating extraterrestrials merely as enemies to be obliterated without any thought for their thoughts, the Geneva Convention not applying to folks from other planets. There’s no imagination of what the cosmos might look like through their eyes. If they even have eyes. Equally flat are films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) or The Abyss (1989), in which extraterrestrial intelligences are benign in some undefined way. It seems a struggle for us to imagine an intermediate reason for aliens to pay a visit between exterminating us and conferring a vague blessing. Might they not have needs of their own?

More satisfying are stories with a moral dimension, involving the risk of establishing a relationship of trust with the non-human. In the recent Arrival, directed by Denis Villeneuve, Amy Adams plays Louise Banks, a linguist called in to analyse the language of an alien species, whose craft have appeared at 12 sites across the Earth. Already this is a departure from genre norms: what is being offered by the alien visitors is language and therefore culture. They may be bringing a message but in the first instance what they offer is a written language: ink shapes elegantly sprayed from a tentacle into a liquid medium, not permanent but hanging in suspension until replaced by the next secreted utterance.

The aliens hold audience in their craft at set times and for restricted periods. Humans ascend through a strange field of forces to find themselves facing, behind glass, giant creatures like octopi, not fully visible, and equipped with seven tentacles rather than eight. The creatures are majestic, their floating language oddly delicate, sharing with the Chinese written character the ability to hold elements in poetic tension as well as an affinity with Japanese brush painting. Each “word” is self-contained and circular, a mandala full of fractal curlicues, generated from more than one point simultaneously, so that it’s impossible to say that there’s a right place to begin or finish reading it.

Arrival acknowledges the forces of unreason—the rioting civilians and paranoiac military wanting action against the invader —but gives priority to the desire to co-operate. If there’s an unsatisfying pious residue here, then what could have been done to sharpen the overall effect? Perhaps the presentation of the Heptapods is too safe—there they are, floating behind their glass, with no possibility of being touched. Our latent distaste for the soft-bodied, the molluscan, is neutralised—except at one moment when a tentacle suddenly presses against the glass, reminding us that this hand is also a mouth and may be an eye.

The films that stay in the memory are the ones where there’s an element of the repulsive to be overcome by character and viewer—a pinch of something disgusting, like asafoetida in Indian cookery, that brings the flavours alive. Empathy that encounters no obstacle can hardly count as empathy. Yet what offends us about imaginary bodies are the same things that bother us about our own bodies: softness where we idealise hardness, lack of boundary when we insist on things staying in their proper place—which, in the case of guts and secretions, is out of sight.

The defining repulsive alien element is gunge. Goo. Sticky stuff. You wouldn’t—for instance—anticipate that it would be worse being savaged to death by a wet set of teeth than by a dry one, but the memorable mucous dentition of the creature in Alien suggests otherwise.

"The films that stay in the memory are the ones where there's an element of the repulsive to be overcome by character or viewer"In the 1999 film Galaxy Quest, directed by Dean Parisot, there are brutal, extermination-minded aliens and downtrodden, childlike ones, their historic victims. The downtrodden aliens set the plot in motion by abducting the cast of a television space opera, mistaking the actors for the parts they play and imagining that these rugged heroes will fight as champions of the underdog, as they have so often done on screen. There’s a scene in which Mathesar (Enrico Colantoni), leader of the pacifists, is tortured by the arch-sadist Sarris (Robin Sachs) so as to extract information from the commander of the Galaxy Quest (Tim Allen). Mathesar has adopted a human guise as a matter of politeness when dealing with the brave humans he admires so much, but the pain makes him revert to his normal form, which resembles a pile of viscera. It’s a brilliantly managed effect, with the repellent image and the jolt of sympathy combined in a single moment of complex emotion. There’s sophistication, too, in David Howard’s screenplay with the trusting agony of the creature under torture, so serenely confident in the power of his chosen allies, twisting the knife in the soul of the commander who is no commander.

By the logic of the plot, the impostors must start playing in reality the heroic roles they took on in a popular television series. By a deeper, stranger logic, the film goes through its own transformation, so that what started out as a spoof (bad-faith genre par excellence) first turns into a homage and then escalates into a non-parasitic excellence, trouncing anything in the Star Trek archive, obviously the original satirical target, in entertainment value and poignancy. Existentialism again, in the form of “good faith”—the decision to behave, in a meaningless cosmos, as if your choices actually mattered.

Computer-generated imagery has something stubbornly untactile about it. Pre-digital effects, making resourceful use of hydraulic bladders and other real devices, were on better terms with the viscosity that does so much to boost the yuck factor, the slurp and squelch of alien tissue. The Pandorans in James Cameron’s 2009 Avatar, for instance, with their big eyes and athletic physiques, mobile ears and expressive tails, seem utterly synthetic. Their lithe blue flesh looks as if it was grown in a tank of pixels. The film’s hero Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) is a paraplegic who discovers a new life when technology miraculously implants him in a fully functioning alien body. It just feels too easy—the film functions more like a video game in a New Age pastoral setting than a humanly (or alienly) engaging drama. Why not at least give the situation a bit of texture, by putting Jake inside a creature less immediately appealing than a bounding steroidal Smurf? A millipede, for instance. The love scenes would certainly be less insipid.

Human gender arrangements and roles are normally taken for granted in science fiction films—Pandoran foreplay, for instance, starts with a non-intrusive kiss before escalating. True, there’s a fairly startling plot development in Enemy Mine, released in 1985, when the scaly alien played by Louis Gossett Jr (best known for his role as the tough gunnery sergeant in An Officer and a Gentleman) dies in childbirth. His species reproduces asexually. Enemy Mine is a sort of remake of John Boorman’s 1965 Hell in the Pacific, except in deep space, sharing its theme of two survivors from opposing armies brokering some sort of truce so as to endure a hostile environment. Clearly, given the realistic genre and setting of the original film, it would be more shocking if either of its stars, Lee Marvin or Toshiro Mifune, were to go into labour, with or without complications. But actually the disruption of gender stereotypes in Enemy Mine is minimal, with Dennis Quaid’s human character Davidge nobly bringing up and protecting the orphaned Zammis—sample dialogue “Uncle, what did my parent look like?” / “Your parent looked like... my friend.” The film ends with Davidge keeping a promise to his dead frenemy by reciting Zammis’s lineage to the Holy Council on the home planet—though why a species that reproduces asexually would be fussed about family trees is anybody’s guess.

Neill Blomkamp’s District 9, released the same year as Avatar, addresses issues of alienness in a much more impressive way. The alien “prawns” in the film are refugees rehoused after their damaged spaceship arrived on Earth, suspended above Johannesburg. The “prawns” are physically disgusting, though resembling insects as well as shellfish—both sets of creatures being arthropods—and most of them are low-functioning, tinned cat food being their idea of fine dining. Their arrangements for incubating their young are particularly unsightly, involving the suspended carcasses of slaughtered cattle. In the course of the film its hero Wikus (Sharlto Copley) metamorphoses into a prawn after exposure to an alien chemical, and comes to understand their reality by the involuntary empathy of inhabiting a body like theirs. In a South African film racial allegory is bound to be part of the mix, though District 9’s portrayal of Nigerians as gangsters got the film banned in that country.

Wikus must come to terms with... slime. And there it is, the word I’ve been tiptoeing around, subject of some famous passages towards the end of Being and Nothingness (Sartre’s original term being le visqueux): “To touch the slimy is to risk being dissolved in sliminess.[...] A consciousness that became slimy would be transformed by the thick stickiness of its ideas.”

In the original 1984 Ghostbusters, “slime” became a verb (“he got slimed.”) Being spattered with non-human juices was a rite of passage, an ectoplasmic blooding that gives access to what Sartre calls “the great ontological region of sliminess.” When Ghostbusters concurs with Being and Nothingness, who among us dare dissent? The confrontation with slime in District 9 is powerfully managed—and yet there’s a limit fixed to the evolution of its hero. Wikus doesn’t start to find other prawns arousing but remains devoted to his wife, humbly leaving tokens of love outside the house he once shared with her. Blomkamp’s follow up to District 9, the dystopian fantasy Elysium, seemed anaemic by comparison, its categories of narcissistic rich and squalid poor not grounded in a bodily dialectic of revulsion and acceptance.

What must be the supreme moment of openness to slime in the movies comes in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth, released in 1976. Mary-Lou (Candy Clark, in a great performance) has been living for years with the alien Thomas Jerome Newton (David Bowie), who has adopted human form. They seem to have been lovers in some satisfactory way without him expressing himself in the way that comes naturally to his species. At various points we see visions of alien bodies spinning gracefully in space and shedding a pearly liquid, presumably a product of arousal.

After a quarrel, Newton decides to show himself in his true form. In the bathroom he reaches down to his genitals (just offscreen), as if minded to unplug them, and pinches the nipples that are likewise prosthetic. He removes his humanoid contact lenses to reveal the eyes beneath, yellow with a vertical slit. When Mary-Lou knocks on the door he reaches for the lock with a hand that lacks fingernails. In his true form he’s also bald. He emerges from the bathroom and walks past Mary-Lou to lie down on the bed. She’s terrified—she wets herself. And then with astounding courage she enters the bedroom, undresses and lies down beside him. His hand on her body leaves a snail trail. It’s too much for her, and she runs away with a scream.

In the moment before her nerve fails does she say to herself, in tones of wonder, “It is a soft, yielding action, a moist and feminine sucking, it lives obscurely under my fingers, and I sense it like a dizziness; it draws me to it as the bottom of a precipice might draw me to it”? No she does not. As I say, it doesn’t seem likely that well-thumbed copies of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness show up on the sets of many space operas. But you never know.