Pedro Almodóvar’s childhood plays out like a scene from one of his films. A little boy, sent away from his village in La Mancha to be educated by salacious priests, takes refuge in the cinema at the end of the street. The setting is Extremadura, in Spain’s arid heartland, where the light is thick and yellow. In the dark cinema, Hollywood divas flicker in alluring close-up. The seminary’s director warns that watching American films may send little Pedro to hell. His friends think it’s odd that he’s more interested in the love life of Ava Gardner than in the usual childhood games. Cue transsexuals, a bullfighter and a plangent bolero.

Those last three elements aside (they came later) it’s curious how many of the themes that preoccupy Almodóvar, now 66, have been with him from the start: Hollywood glamour, religious oppression, the liberating power of transgression, the love of family. The filmmaker, whose work is being celebrated by the British Film Institute in a season running throughout August and September, has made a colourful career of his obsessions. That, in turn, has made him the world’s most famous film director not working in English. “In terms of dramatic creativity there are three Spanish icons,” says academic and critic Maria Delgado: “Cervantes, Lorca and Almodóvar.”

Like Cervantes, Almodóvar comes from La Mancha and like Lorca, his childhood was, in his own words, “very folkloric.” His father hauled barrels of wine by mule. His mother read and wrote letters for illiterate neighbours in the village and taught Almodóvar to do the same. In 1949, the year he was born, poverty in Spain was such that whole villages in the south abandoned their homes and migrated north looking for work. In the early 1960s, Spain’s ruler General Franco approved an apertura, a cautious opening of the country to foreign influences, partly intended to encourage tourism. Its unintended consequence was to show young Spaniards how different life could be.

Defying his parents, Almodóvar moved to Madrid in 1967, aged 17, got a job in a phone company and was quickly absorbed into a night-time scene of artists and performers chafing against the old order. In 1970 the Ley de peligrosidad social (Law of Social Danger) gave the police powers to arrest anyone who, like Almodóvar, appeared homosexual. The same year, the National Film School was branded a “hotbed of communists” and closed down. Almodóvar taught himself film, showing his Super 8 shorts at underground parties and events in Madrid and Barcelona. His younger brother Agustín (these days his producer and business partner) provided sound from a cassette player.

When Franco died in 1975, the fledgling director was perfectly positioned to chronicle the creative revolution that followed, the famous Movida (movement). That was the decade when Madrileños stopped sleeping and started partying. Almodóvar’s early films are a riot of transgression: dope-smoking nuns vie with rent boys, porn stars and incestuous transsexuals. Housewives get it on with strangers in showers. What Have I Done To Deserve This? (1984) was set on a grim estate Franco had built to house migrants from southern Spain. Carmen Maura, the first of Almodóvar’s chicas—the actresses he works with regularly—is a sexually frustrated housewife who lends her son to a paedophile dentist (with the boy’s consent). In Law of Desire (1987), Antonio Banderas is a psychopath who has anal sex on screen. There’s an element of cinematic Tourette’s syndrome to those early films—every scene a taboo-busting rush of sex and violence—but there is also subversive humour and an affection for the marginalised and misfits. It’s easy to forget now how revolutionary they were. Almodóvar was debating, and depicting, “gender fluidity” 30 years before it went mainstream.

For Delgado, “the films are political whether Almodóvar intended them to be or not. The key thing was the freedom after Franco. He reflected the changing tempo of the times, making extremely mature cinema in an immature country. It was radical, bold work.”

If they seem absurdly extravagant to a contemporary eye, Almodóvar’s fantasies were not altogether excessive. When I lived in Madrid as a student in the late 1980s, transsexual prostitutes and drug-addicts were as likely to be found drinking in our local bar as elderly widows or retired policemen. Cannabis had been legalised, sex could take place anywhere the light was dim enough. Noise, parties and traffic jams went on all night. Madrid was dubbed “capital of the century.” But by the century’s end, that star was waning. What had felt like a new way of life turned out to be a wild interregnum, fuelled not only by euphoria but by the fear that dictatorship could return and all the old restrictions be reimposed.

"Almodóvar was more interested in the future than the past. He neither lingered on the country's traumas nor satirised them"Almodóvar’s cinematic vision liberated Spain sexually, religiously and—more importantly—from a century-old cultural inferiority complex. For decades writers had been absorbed by the “problem” of Spain. Almodóvar was more interested in the future than the past. He neither lingered on the country’s traumas nor satirised them as his predecessor Luis Buñuel had. His version of Spain was fresh and funny and alluded only obliquely to social problems. Serious subjects were treated lightly; melodrama got taken seriously. Almodóvar’s stories still blend radical ideas with an affection for Spanish touchstones, including flamenco dancers, bullfighters and Iberian jamón—the murder weapon in one film. His characters live in Madrid but often yearn to go back to the pueblo (the ancestral village). Family is at the heart of everything. His relatives often appear on film: cousins, nephews and nieces are part of the team on set. His mother advised on Manchegan dialogue.

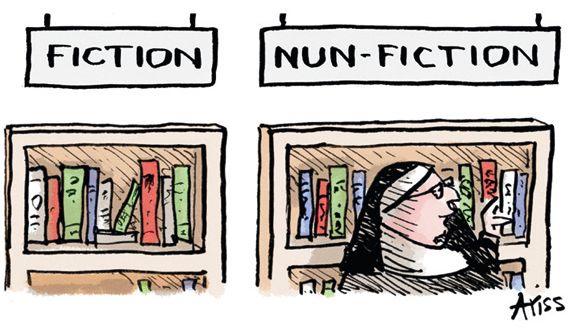

There is a bawdiness in Almodóvar’s work that taps into an essentially Spanish approach to life, one that dates back at least to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Unlike its British equivalent, Spanish humour has never turned on a nudge or a wink; there is a frankness to everyday conversation that can be disconcerting to outsiders. Fat people often get called “fattie,” bald people, “baldie.” This is a country where you can innocently ask for a bag of “nuns’ tits” in a bakery and come away with some suggestively-shaped marzipans.

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988) was Almodóvar’s first commercial hit outside Spain and the films that followed, including Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990), High Heels (1991) and All About My Mother (1999) earned him a cult status. “When he came to Harvard for an honorary degree the reaction was stunning,” says Brad Epps, professor of Spanish at Cambridge University. “Kids were literally throwing themselves at him. We had to push our way through. And I mean Joan Didion was behind us.”

Part of his appeal is that he champions women, and not just pretty ones. “He recently told me that there are two kinds of women in his films,” says Delgado. “One is based on his mother and her friends, gossiping in the patio, putting the world to rights. Fathers were important too as the authority figures, but they were usually away. So the stories come from the women. The second kind of woman is associated with La Movida—strong, independent women, agents of their own life and change. Those are two solid models he returns to again and again.”

For some critics Almodóvar has returned too much to the same themes, dangling transgression before eyes that have grown weary of shock-tactics. That’s partly because the rest of the world has caught up, says Epps. “Popular culture is awash now with gender-bending characters and so it becomes more and more difficult to find the transgression that was so easily found after 40 years of National Catholic dictatorship.”

Any criticism of the sexual content has perhaps been too readily dismissed as Anglo-American puritanism. Films like Kika (1993) and The Skin I Live In (2011), portraying rape, suicide, imprisonment and mutilation, divided critics and audiences outside Spain. Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! was given an X rating in the United States, effectively disqualifying it from general distribution. Almodóvar sued the Motion Picture Association of America, accusing it of being no better than Franco, and he won. A new classification was invented for him: NC17 (no children under 17).

On occasion Almodóvar himself has seemed squeamish about where his own ideas lead him. When making Bad Education (2004), he brought child psychologists on to the set. “The little boys were playing characters who grow up to have sex changes, get addicted to heroin and commit murder; all that could have left ghosts in their minds.”

If the subject matter is contentious, the cinematography always wins plaudits. Almodóvar’s mature style is highly polished and all his own. Scenes are shot in vivid colour, with bright red a recurring motif. Epps, who spent several days on the set of Broken Embraces, remembers the director rejecting the gazpacho that was to have been a prop. “A real gazpacho should be salmon colo ured and that was how they had made it for him. Almodóvar said it must be blood red.”

"He sued the Motion Picture Association of America, accusing it of being no better than Franco, and he won"Less obvious are the cinematic and artistic references that pepper his work. Melodrama, film noir, Italian neo-realism and the Spanish comedies of the 1950s and 1960s all get a nod. Billy Wilder is his acknowledged master. But there are also myriad references to art and literature. The cinematographer on Dark Habits (1983) was told to light it as though it were a painting by Francisco de Zurbarán. A copy of Alice Munro’s collection of stories Runaway appears in The Skin I Live In (2011), a hint that he was already planning Julieta, his most recent film, which is based on three stories from that collection and comes out in August.

People who have worked with him testify to Almodóvar’s attention to detail. He rehearses actors for months, as though preparing for a play. He will halt a scene to change the drape of a piece of material. “He’s amazingly meticulous,” says Delgado. “Spain has been rushing headlong into things, racing forward with the Pacto de olvido [the Pact of Forgetting, an agreement not to pursue political grievances related to the dictatorship], with the European Union legislation and new democratic freedoms. By contrast, he’s not afraid to take his time.”

It is partly that attention to detail that has prevented Almodóvar accepting invitations to work in Hollywood, although he has often expressed an interest in working in English. In fact Julieta, his 20th film, was to have been his first English-language project, reportedly with a role for Meryl Streep. Ultimately the director decided that he could not relinquish the control that comes with working in his own language.

Julieta, centring on a woman estranged from her daughter and confronting various demons, finds the director in a sombre frame of mind. “He was looking for a leaner film, more restrained, a stripping away,” says Delgado. “It’s a film about loss and mortality and how to live with the regrets in your life. He’s got a hearing impediment and photophobia [extreme sensitivity to light]. Increasingly his work is about frailty.”

The climate of euphoria and freedom that formed Almodóvar has long gone. “Spain is in a different place. He is in a different place,” says Delgado, who lunched with him on the day of the Brexit result. “He was horrified. We discussed the implications, the rise of the right wing, the way that has affected so many aspects of culture. The church in Spain had recently taken offence at a gay pride event. They thought they had shaken off those shackles, but the atmosphere is very different now. He wouldn’t be able to make those early films now.”

classics. The season at the BFI will include some of those favourites. Increasingly, Spain’s forward-looking director looks to the past. Age and fame have made him a part of the canon. There’s even a park named after him in La Mancha. Nobody can stay an enfant terrible forever.

"The Almodóvar Collection", a brand new boxset of six newly restored films from Pedro Almodóvar’s early career, will be released on DVD and Blu-Ray on September 19 by STUDIOCANAL, complete with brand new interviews and extras material. The BFI Southbank in London is currently hosting a season of events on Almodóvar which finishes in October.