In 1938, Frida Kahlo was discovered by André Breton, proclaimed a surrealist and launched on to the international art scene. Breton had met Kahlo—then famous for being the wife of muralist Diego Rivera—in Mexico and been dazzled by the work and the woman, whom he approved of as being “endowed with all the gifts of seduction,” and “accustomed to the society of men of genius.” When Kahlo arrived in Paris, some of those lucky geniuses, including Picasso and Kandinsky, were similarly impressed by the work, or the woman, and perhaps both.

Kahlo didn’t return Breton’s compliment. She was no surrealist, she said, because her paintings depicted, not dreams, but real events in her life, including a disabling accident, troubled marriage and childlessness. Writing to a friend, Kahlo described the surrealists as self-satisfied and unhygienic, even worrying that she might have caught something nasty while staying in Breton’s flat.

“None of them work and they live as parasites of the bunch of rich bitches who admire their ‘genius,’” she said. Most of the group were “cockroaches” and “big cacas”—both items that would sit happily in a surrealist canvas. She also had harsh words for the continent from which they emerged. “I am nauseated by all these rotten people in Europe—and these fucking ‘democracies’ are not worth even a crumb.” Americans didn’t fare much better: she thought gringos looked “like unbaked rolls.”

Since Breton’s presumptuous appropriation, Kahlo has been claimed, adored and misrepresented by countless groups, artistic and otherwise. An artist who had barely been written about or exhibited during her lifetime is nowadays the subject of hundreds of studies and exhibitions, with major retrospectives all over the world. She has become much more famous than the very famous man she married. In June an exhibition at the V&A of Kahlo’s clothes and personal possessions—Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up—is set to be a summer blockbuster. The merchandise alone promises to be wonderful.

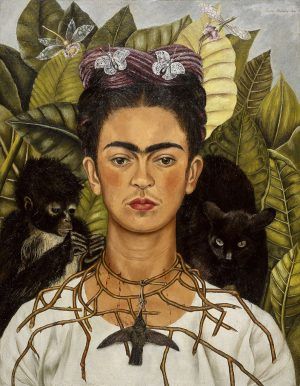

What makes Kahlo so marketable? Her art, characterised by gorgeous colours and enigmatic themes of injury, love, betrayal and thwarted motherhood, looks wonderful on the canvas—and transfers nicely to t-shirts. A quick internet search finds her gracing everything from trainers to sanitary towels. The famous face, gazing out of some 200 self-portraits, is both beautiful and unconventional, with thick eyebrows that join in the middle and the hint of a moustache. It’s part of the portraits’ appeal that her face always looks the same, as though worn like a mask. Kahlo described herself as la gran ocultadora—the great concealer—and there is something totemic about her portraits that speaks to an age when self-representation is both pervasive and untrustworthy. Kahlo can be what we want her to be: a feminist, wounded lover, cultural ambassador, survivor of disability, sexual adventurer. I can have my Frida; you can have yours. With the right software, that combination of beauty, defiance and colour can be scaled up or down as needed: cute Frida for emojis and children’s picture books; edgy Frida for a book on queer icons. It helps that the artist also produced a few soupy aphorisms. “You deserve a lover who takes away the lies and brings you hope, coffee and poetry,” is currently playing well on Twitter.

These days Kahlo can be found in all the places we used to see Che Guevara, another Latin American communist who has shifted a fair bit of merchandise in his time. But whereas Che t-shirts and badges tend to end up on people who are at least partly sympathetic to his cause, Kahlo the communist is not popular with merchandisers, even though she was involved with the Party, one way or another, all her life. She joined the Mexican Communist Party at the age of 20. In one of her last paintings, Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (1954), a saintly Marx passes down Das Kapital and enables Frida to throw away her crutches. Kahlo also had an affair with Leon Trotsky, three years before his assassination in Mexico, that so galvanised the old revolutionary, he wrote a nine-page letter begging her not to leave him. Her response was “estoy cansada del viejo” (I’m tired of the old man).

While the orthodoxy of Kahlo’s communism is questionable, her socialist instincts and her commitment to marginalised groups were sincere and life-long. In the rush to commodification, though, ideology is easily cast aside; faces of famous communists are massified in defence of ideologies they did not espouse. So selfie queen Kim Kardashian can, without apparent irony, appear as Frida on Snapchat. Theresa May can wear a Frida bracelet at the Conservative Party conference with barely a murmur of surprise. Kahlo’s image has become so ubiquitous, so resilient to interpretation, that I can admire her monobrow en route to the threading salon, without feeling like a hypocrite or someone who’s missed the point.

And, in this case, eyebrow management is a feminist issue. Last December we learned how, among his many vile assaults on women, Harvey Weinstein tried to tidy up Frida’s brow in the 2002 film which had been brought to him by Salma Hayek. The actress revealed in the New York Times how, over several years, Weinstein bullied, threatened and harassed her as she tried to bring her project to the screen, continually placing obstacles in her way when she refused to submit to his sexual advances. Among other demands, he wanted a sexier Kahlo. The limp and the monobrow must go and there must be full frontal nudity and sex scenes with another woman. To save her project, Hayek finally agreed to the sex scenes, but she was adamant in defence of Kahlo’s facial hair. No one messes with the monobrow.

***

Kahlo would more likely have considered herself a daughter of the revolution than of the patriarchy—she always claimed 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution, as her birth date, though really she was born three years earlier. Her father was German, her mother a mestiza Mexican and her name was “Frieda” until post-war sentiment made it advisable to drop the “e.”

At the age of seven she suffered polio, which withered her right leg. Perhaps her disability led her family to indulge or encourage a contrary streak; Kahlo appears in an otherwise conventional 1926 family photograph dressed in a man’s suit and tie, as though anticipating her 1940 canvas Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair. Her father, also an invalid, encouraged her to take up boxing to improve her strength and took her to work with him in his photographic studio. Her schooling was extraordinarily progressive. The Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in Mexico City was run along lines set down by the education minister, José Vasconcelos, a leading figure of the revolution, who believed that art could inspire social change, and that the country’s indigenous heritage—not European colonialism—was the key to Mexican advancement. Social activism was on the curriculum, along with lectures on new ideas, artistic excursions and debating. Aged 15, Kahlo may have met Diego Rivera when he was invited to the school to paint a mural.

She had planned to study medicine but in 1925, at 18, Kahlo had the accident that was to define her life and her art. The bus in which she was travelling with boyfriend Alejandro Gómez Arias was crashed into by a streetcar, and a metal handrail was forced into her body, through her spine and out of her vagina. (“I lost my virginity in that accident,” she would later say). She sustained terrible injuries to her back, pelvis and right foot. In Gómez Arias’s account, Kahlo’s clothes were torn off during the accident and her body was covered in the gold powder a fellow passenger, an artist, had been carrying. Naked and golden, she was reborn as an icon.

During Kahlo’s year-long recovery, while her body was encased in plaster, she started to paint. At least 30 more operations followed in the course of her short life (she died at 47), bringing with them periods of immobility that Kahlo enlivened by painting on small canvases. Perhaps no artist has created such a comprehensive study of pain and the consequences of a devastating injury. Kahlo was to lose three pregnancies as a result of her damaged pelvis. In some canvases her body is shown wounded and dripping blood, with vital organs outside her body and veins, like tendrils, wrapped around her neck. Along with physical pain, Kahlo depicted the emotional pain caused by Rivera’s constant infidelity. Towards the end of her life, after her right leg had been amputated at the knee, a mirror was attached to the canopy of Kahlo’s bed, so that she could more easily paint lying down.

No matter how dark or gruesome her subject matter, Kahlo’s paintings are always bright. Inspired by José Vasconcelos’s indigenismo, she, Rivera and other artists agreed to reject the “intellectualism of the easel.” They would avoid European styles and colours in favour of the untutored schemes used in indigenous art. Her counter-intuitive use of colour helped Kahlo to create a visual language all her own. In her diary she recorded a key to the different colours. Yellow represented “madness, sickness, fear”; cobalt blue “electricity and purity. Love.” In My Birth (1932), which belongs to Madonna, her most devoted collector, an adult Frida is shown being born in a blue-painted room to a woman whose upper body is hidden under a sheet. The effect is both tranquil and disturbing. “If somebody doesn’t like this painting,” Madonna has said, “then I know they can’t be my friend.”

Kahlo always downplayed her talent, preferring to praise Rivera—although he said that she was the better painter and many others agreed. Self-effacement, as with the mask-like portraits, may have been a way to protect herself. Kahlo refused to compromise her ideas in order to make her art more attractive to collectors. She always claimed that Rivera was her life’s passion, not her work.

***

Art made for an audience—and often a market—can’t help but be self-conscious. On the other hand, there is something especially affecting about a person’s possessions and clothes. Cherished objects offer private access to their owner and come loaded with meaning—sometimes unbearably so.

Suffering artists have always been attractive, but the possessions of tragic women seem particularly to resonate. The critic Terry Castle has written a little cruelly, but perhaps not unfairly, of the “ambulance chaser” fans who fawn over artists like Kahlo and Sylvia Plath. There is a morbid appeal in the paraphernalia of a life cut short. In the case of both women, their admirers’ tendency towards tragic romanticisation risks diminishing the originality—and violence—of their work.

The momentum supplied by social media has fed an intense personalisation of women’s art or writing, with some of it being placed beyond criticism, because criticising is seen as disputing the artist’s achievement or straying from principles that have lately become sacrosanct. Kahlo never claimed this status for herself—she was far too self-doubting; we have thrust untouchability on her.

She was, as Tony Blair might have put it, the people’s artist, making an artwork of herself and her life in ways that could draw comparison with Tracey Emin, today. Kahlo would even arrange the dinner table as an art work, with objects that changed daily, including pottery, flowers, a bird in a cage. She dressed strikingly, in traditional Tehuana dresses and floral headbands. The Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes recalled her making an entrance at a concert one evening, and drowning out the music with the noise of her jewellery.

After Kahlo’s death in 1954, Rivera put her belongings away with the stipulation that they remain under lock and key until 15 years after his death. In fact, the room was not opened until 2004. The exhibition at the V&A—which marks the first time the collection has been shown outside Mexico—therefore comes with the cachet of a fairy-tale enchantment, as well as the familiar pull of propinquity. After 60 years, the artist awakes. Whose Frida will she be? I’ll see you in the shop.