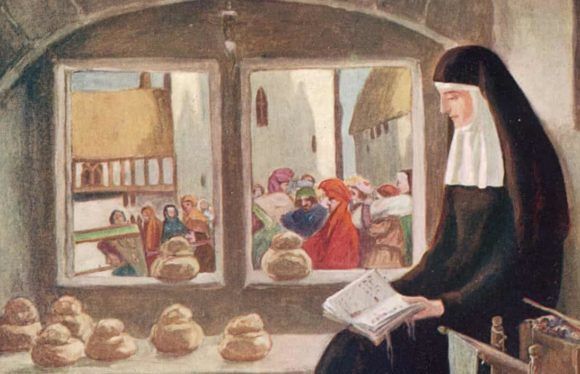

An illuminated manuscript showing an anchorite.

Isolation is a strange thing. It is used as punishment—solitary confinement, house arrest—at the same time as people seek it out through retreats and wellness therapies. As a society we value people who are gregarious and fun, but throughout history we have sought out those who live in isolation for wisdom and guidance. Hermits, gurus, mystics, even artists and authors who are notoriously private about their personal lives—these individuals have long been objects of fascination.

There is a cultural pressure on a state of isolation to produce something profound. We expect to find some great truth or wisdom in isolation, or to finally have the space and time to write a magnum opus, a novel, a screenplay, a symphony. In the past few days on Twitter, there has been chat about how Shakespeare wrote King Lear and all of the sonnets while the theatres were closed during the plague. We expect that our experience of time will stay the same, and that the hours that were filled with commuting, office banter, socialising and pints will now need to be filled with an equal number of activities, done in solitude.

So as we all farewell our friends and loved ones with a pat on the elbow, buy enormous quantities of tinned tomatoes, and prepare to enter a period of confinement, it might be a good time to consider the anchorite.

Anchorites and anchoresses were religious devotees in the Middle Ages, predominantly women, who sealed themselves into stone cells attached to churches and cathedrals to serve out their days in prayer and contemplation. To become an anchorite, the prospective candidate had to write to the bishop and show that they were ready to be enclosed. They had to prove that they had sufficient financial means to support themselves in isolation, and one or two servants to bring food, take away waste, and help them with tasks in the outside world.

When an anchorite was ready to enter isolation, they were administered last rights, and a priest would say the prayers that are said at a funeral, symbolising the fact that the anchorite was about to be dead to the world, entering a space that would become their tomb. A cell would be prepared that had two windows: one looking into the church so that the anchorite could participate in mass, and one looking out to the world so that they could converse with visitors and people seeking religious guidance. After the enclosing ceremony, the anchorite would then enter their cell and the door would be sealed.

Texts from the period give some indication as to why people would choose this life, and how they should go about living it. A life of asceticism and restraint was thought to bring a person closer to God through suffering. The fact that there were many more anchoresses speaks to a period of history where women’s bodies were seen as disobedient vessels of sin that needed to be restrained and made to behave. It was strongly advised that anchoresses not speak with visitors for too long, in case their unruly bodies took over—in De Institutione Inclusarum, a guide for anchoresses, the monk Aelred of Rievaulx warns of their cells becoming “a brothel” if they spent too long convening with the outside world.

So what did they do with all that time, all those years spent in solitude? Writing from the time suggest that they did some manual work like metalwork or lace-making, and they also read and wrote religious texts. For the most part, they just thought—contemplating their beliefs, praying, considering their place in what they knew of the universe. They spoke to visitors and offered advice and prayer, and probably spent many, many hours sitting alone and in silence, letting time wash over them.

The most well-known anchoress is Julian of Norwich, who was confined in a cell attached to St Julian’s Church in Norwich during the Middle Ages. Julian herself was familiar with plagues and pestilence—she was a child during the Black Death, and lived through a period where up to half of Norwich’s population was killed by the disease.

Whilst confined as an anchoress, Julian wrote what is considered to be the earliest surviving English-language book by a woman, Revelations of Divine Love, which is about her religious visions whilst in isolation. In 1413 she was visited by the medieval diarist Margery Kempe, and the two women spoke together. It's incredible to think that the authors of two of the only surviving texts by women from the period not only crossed paths, but sat together and had a conversation, which Margery then recorded in her diary. An isolated encounter has reverberated through the centuries, and is somehow able to say something to us today, in these strange and unexpected circumstances. Julian’s writing, and contemporary accounts of discussions that she had with various people, all point to her unfailing optimism in times of adversity and isolation—something that feels pertinent for many of us at the moment. Her legacy is about faithfulness in the face of turmoil and truly believing, as she wrote, that “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”