It is 50 years since the series of events known as Watergate unfolded: the foiled break-in on 17th June 1972 to replace a listening device at the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in the Watergate office building; the flood of revelations about crimes and dirty tricks in 1973 that engulfed the Nixon administration; and the president’s eventual resignation on 8th August 1974. During this run of anniversaries, attention will inevitably focus on the political and constitutional legacy of Watergate—especially the parallels between Nixon’s abuse of power and Donald Trump’s disregard for norms and conventions.

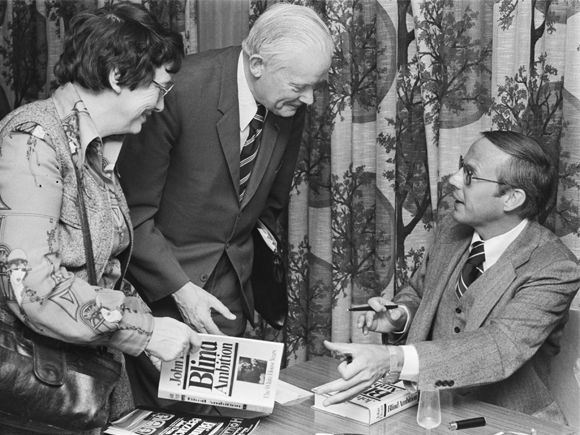

But the affair was also a literary phenomenon: in the 1970s Americans gorged on Watergate-related books. These ranged from self-serving memoirs and autobiographies to political thrillers, as well as a new hybrid genre pioneered by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, that served up the quest for truth in a form resembling a police procedural. In 1976, almost two years after Nixon’s downfall, Watergate titles occupied four of the top 10 positions in the US non-fiction bestseller list. In 10th place was a memoir by the Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski; in eighth, the autobiography of Nixon’s one-time counsel turned whistleblower, John Dean; in fifth, Born Again, the evangelical conversion narrative of Nixon’s hard-boiled aide Charles W Colson; and at the top was Woodward and Bernstein’s second bestseller, The Final Days, which had sold over 600,000 copies. The Hollywood film of the pair’s first book, All the President’s Men, was the sixth highest earning movie of 1976. Four years on from the burglary, the appetite for revelations about the inner workings of Nixon’s government was far from sated.

The scandal also bequeathed us with what we might call the Watergate plot, which revolves round criminal escapades, surveillance, bugging, cover-ups and presidential tyranny. More extraordinary, perhaps, is that the protagonists in the scandal themselves helped to shape this Watergate genre. Writing a novel provided one way for Nixon’s men caught up in the legal maelstrom—such as his chief domestic adviser John Ehrlichman and his disgraced vice president Spiro T Agnew—to pay lawyers’ fees or forge new post-Watergate careers.

E Howard Hunt, the ex-CIA man turned White House consultant who organised the Watergate break-in, had been an established thriller writer since the 1940s and was once plausible enough to have won a Guggenheim fellowship. Over the course of his career, Hunt would publish around 70 novels, both under his own name and various pseudonyms: Robert Dietrich, Gordon Davis, David St John, PS Donoghue. So inexorable was the conveyor belt that he found himself correcting galley proofs of his Berlin Ending (1973) while doing time in a DC jail. Appropriately enough, in Hunt’s later novel The Hargrave Deception (1980) his hero’s comeuppance takes the form of testimony before a Senate committee.

So was the Watergate burglary itself a bizarre case of fact reflecting the fiction of one of its perpetrators? To this day, nobody knows who ordered the break-in. Nor has anybody suggested a plausible reason why—given the crazy risks involved—Nixon’s aides might want to tap the phones of the DNC. Was the assignment the folly of Hunt’s zealous colleague G Gordon Liddy, whom Hunt described caustically as “a candidate for decaffeinated coffee”? Or were such comments a smokescreen for Hunt’s own responsibility? The logic behind the break-in and bugging made sense only within the plotlines of the second-rate thrillers Hunt churned out.

Was the Watergate burglary a bizarre case of fact reflecting the fiction of one of its perpetrators?

However, there was more to Watergate than a botched break-in. The scandal involved multiple storylines and unexpected twists and turns, teemed with sub-plots, and had at its core a tormented president of Shakespearean depths. For novelists, as well as political journalists, it was the gift that kept on giving.

Watergate simmered for months before the scandal boiled over. Although the foiled burglary made headlines, the story soon subsided. Nixon and his retainers organised a cover-up designed to get them through to the November election in which he was triumphantly re-elected, winning every state in the country bar Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Watergate was a mere blip in his unstoppable progress to a landslide victory.

But after his re-election the cover-up fell apart. Prime mover in puncturing the secrecy was John J Sirica, the judge in the trial of the Watergate burglars. Living up to his nickname “Maximum John,” a suspicious Sirica threatened the burglars with lengthy sentences if they wouldn’t breach their code of silence. James McCord, the electronics expert responsible for planting the bugging devices, broke ranks and informed Sirica that more senior figures were involved.

There followed weeks of panic among Nixon’s advisers. The White House counsel, John Dean—one of a group of senior officials purged from Nixon’s administration in April 1973 for their involvement in Watergate, including Ehrlichman and Nixon’s chief of staff Bob Haldeman—could see that he was being set up as a scapegoat. He flipped.

Dean gave devastating televised evidence to the Senate Watergate Committee that the president had been complicit in the cover-up. But it was the word of a seemingly duplicitous White House functionary against that of the president. In the summer of 1973, it became possible to test the veracity of Dean’s claims. Another White House official, Alexander Butterfield, testified that Nixon had installed recording systems in the rooms where he worked in the White House. The notorious meeting where Dean supposedly told the president about the cover-up had been taped. But Nixon contested the special prosecutor’s access to the tapes.

As the scandal unfolded, Nixon lost his best insurance policy against impeachment: the offensively outspoken Spiro Agnew. Much as they despised Nixon, his liberal opponents had serious qualms about replacing him with his thuggish vice president. However Agnew, who was under investigation for the bribes he got from local contractors while governor of Maryland, cut a deal with prosecutors and announced his resignation on 10th October 1973. In return for pleading no contest to charges of tax evasion Agnew would not do jail time for bribery, but had to pass the vice presidency to Gerald Ford.

There followed a series of tussles for access to the tapes. The first culminated in the Saturday Night Massacre of 20th October 1973, when Nixon ordered the Department of Justice to fire the Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox, but in the process lost both his attorney general Elliot Richardson and Richardson’s deputy, William Ruckelshaus, neither of whom would agree to Cox’s sacking. (The third in command, Robert Bork, did the president’s bidding.) The tug-of-war over the tapes eventually reached the Supreme Court. By 8-0 the justices found that Nixon’s claims of executive privilege did not allow him to withhold evidence in a criminal prosecution. The requested tapes were released, including the notorious “smoking gun” tape of 23rd June 1972—only a few days after the burglary—where Nixon could be heard plotting with Haldeman to use national security and purported CIA involvement in Watergate to deflect the FBI’s investigation into the break-in. On 8th August 1974, Nixon announced his resignation in a televised address.

Events become myths when they enjoy a measure of familiarity with the public that enables recycling and retelling. The televised Watergate hearings in the late spring and summer of 1973 riveted the nation. Ninety million Americans watched all or part of Dean’s testimony to the Senate committee. Watergate proved addictive. People became aware in intimate detail of the inner workings of the Nixon administration and a hitherto behind-the-scenes cast of political operatives—aides, campaign functionaries and irregulars—became household names: Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Dean, Magruder, Colson, Butterfield, Segretti. Watergate became instant myth. Curiously, Nixon, Haldeman and Colson can be heard on the tapes moonlighting as would-be literary critics, at the publication in 1971 of Philip Roth’s crude pre-Watergate satire on the Nixon administration, Our Gang. Roth’s central character, president Trick E Dixon, is eventually assassinated and goes to hell, where he starts campaigning against Satan for high office. All too predictably, Nixon and his henchmen focus on Roth’s obscenity, his Jewishness and how the Kennedys might respond to a satire which includes a presidential assassination.

By a delicious irony, the principal begetters of the Watergate novel were Nixon’s former men—specialists in lies, half-truths and evasions. Nobody did more to shape the Watergate novel than Ehrlichman, the most versatile and sophisticated of Nixon’s henchmen. Ehrlichman practised as an architect before moving into politics and was a prophetic voice on behalf of environmentalism in the president’s administration. He was a moving force behind the Environmental Protection Agency and legislation for clean air, clean water and the protection of endangered species. After serving 18 months in prison for Watergate-related offences, Ehrlichman transitioned from politics to novel-writing and proved himself a highly proficient purveyor of genre fiction. He wrote three novels about the Nixon regime: The China Card (1986), about Nixon’s opening to China, and two very different angles on Watergate. In The Company (1976), he examined a Watergate-like scenario from the perspective of the intelligence agencies, while in The Whole Truth (1979) he focused on the experiences of a John Dean-like fall guy.

Ehrlichman the novelist posed as gamekeeper turned poacher, distancing himself from Nixon’s secretive authoritarianism. In The Company he clearly aligns himself with the cautious bureaucratic establishments that ran the intelligence agencies. The action is seen through the eyes of a character based on Richard Helms, a career CIA official who became its director under Lyndon Johnson, and whom Nixon had kept on at the agency. Lumbering, risk-averse officialdom, Ehrlichman suggests, provides a necessary check on would-be autocrats and populist adventurers.

Events become myths when they enjoy a measure of familiarity with the public that enables recycling and retelling

In The Whole Truth, Ehrlichman let in further unwelcome daylight on his former colleagues. He portrays a boozy, unpresidential Nixon equivalent called Hugh Frankling; an unscrupulous version of attorney general John Mitchell and his wife Martha; and a Dean-like character turbo-charged with ambition. President Frankling engages in the politics of deniability, discreetly authorising an anti-Marxist coup in Uruguay outside the usual channels. Frankling uses Robin Warren, a junior White House counsel—the Dean equivalent—to make approaches to the CIA at desk officer level. The final decision is taken during a sail on the presidential yacht. But the coup fails, and in desperation to shuck off responsibility, the president decides to make Warren a scapegoat. Although the White House utilises every lever to cover up the president’s meeting with Warren—having log books altered, dispersing the yacht crew to the corners of the globe—Ehrlichman shows the impossibility of covering up the truth.

In a last-ditch attempt to save his presidency, Frankling confesses in a televised address that the national interest precludes the president from telling the truth at all times. Indeed, the ultra-Nixonian Frankling redefines the obligations on the president and the meaning of truth itself—and gets away with it. As Warren’s lawyer concedes, with wise ironic acceptance, the American people “expect” the president “to lie, in good faith, so to speak.”

By contrast with the liberal—or cynically faux-liberal—remorse Ehrlichman appeared to express in his novels, Spiro Agnew’s thriller The Canfield Decision (1976) doubled down on the liberal enemies of the Nixon administration. On top of the standard Watergate tropes—a cover-up, damning tape recordings, a break-in—Agnew’s novel featured a series of snarling antisemitic attacks on the Washington Post and Newsweek—their owner Katharine Graham depicted here as Karen Rankin, owner of Twiceweek. Agnew’s principal target was what he referred to as “advocacy journalism,” but it was the glaring racism that caused controversy. Reviewing Agnew’s novel, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith thought Agnew’s style veered from the overwrought to the flaccid, the prose an unstable mixture of the “bureaucratic,” the “alliterative” and a weird strain of “technical baroque.” Yet Galbraith insisted—presumably with his tongue in his cheek—that Agnew should not be dissuaded from pursuing his new career as a writer: “No good citizen will urge Mr Agnew, as he might another writer, to return to his previous way of life. All will want him to keep on trying.”

A more gifted, but more ambiguously positioned, contributor to the genre was former Nixon speechwriter William Safire, once a bugging target himself. Safire, whose columns on language would later become an established fixture at the New York Times, riffed ingeniously on the theme of the cover-up in Full Disclosure (1977). Deceptively, the novel begins with a short-lived attempt to cover up the blindness of an American president seriously injured in an ambush at a summit in Yalta. However, hopes that the loss of sight might be partial or temporary are dashed. President Ericson, his aides, Congress and the American people are forced to come to terms with major ethical and constitutional issues. If a president is of sound mind, but struggling to live as a blind person, how reasonable is it to invoke the 25th Amendment, which removes an incapacitated president? Surely a president with a mandate is allowed a certain leeway?

But then Safire springs on us a further cover-up. What if the president when still a candidate hadn’t levelled with the electorate? The real cover-up, it transpires, occurred before he was elected: in the course of a sexual rendezvous Ericson had an accident that led to a previous bout of temporary blindness.

A comic variant of the cover-up plot surfaced in The Body Politic (1988) by Agnew’s former press secretary, Victor Gold, and Lynne Cheney, wife of the future vice president Dick Cheney. Their premise—ironically enough given Dick’s future role as deputy to George W Bush—was the utter pointlessness of the vice presidency: what if the veep dies and nobody notices? Vice president Vandercleve passes away from a heart attack while making love to his mistress, a TV newscaster. The incident occurs on the eve of a crucial presidential primary in Wisconsin, and the decision is made to delay issuing the news. But it’s never quite the right time to reveal the truth.

But let’s face it: politicians, notwithstanding their gifts for evasion and double-talk, ultimately lack imagination. However intricately woven the political thrillers devised by Nixon’s men, their efforts hardly bear comparison to the way literary novelists transpose Watergate to other planes, or reassemble the elements of the myth in unexpected forms. In Jailbird (1979), Kurt Vonnegut traces the career of a convicted Watergate felon, the fictional Walter F Starbuck, a lowly special adviser on youth affairs whose office is used by senior White House aides to stash a million dollars’ worth of illegal campaign -contributions.

Philip K Dick’s Radio Free Albemuth (1985) uses a science-fiction story of interplanetary contact as a means of exploring the quasi-fascistic American regime of president Ferris F Fremont. Austin Grossman’s Crooked (2015) takes as its point of departure the lack of any convincing explanation—even now—for why Watergate happened. Instead Grossman suggests that the scandal covers up something far more gruesome: a shamanic contest to conjure up dark supernatural forces. Nixon re-emerges, still sinister though more sympathetic, as a reluctant sorcerer-president.

These novels were self-conscious reworkings of an established Watergate myth. Muriel Spark, on the other hand, who completed her novella The Abbess of Crewe before Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, debunked the myth before it had fully taken shape. The idea for a Watergate satire set in an English nunnery came to Spark in November 1973 when she was holidaying in Sri Lanka. She noticed that, in her local newspaper, Watergate appeared below the fold at the bottom of the page: an indication to Spark that Watergate was a subject ripe for bathos and comic deflation. Further inspiration came from a dinner party in May 1974 with her publisher, the former prime minister Harold Macmillan: when he had met the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow in 1959, Macmillan recalled, they had walked in the garden to evade KGB eavesdroppers, though Macmillan suspected that there were microphones in the trees—as there would be in Spark’s abbey of Crewe.

Oddly, there is barely a hint of disapproval in Spark’s satire. Instead she invests her central character, the Abbess Alexandra, with un-Nixonian characteristics: an incongruous glamour and a seductive charisma. She is enraptured by Alexandra’s taste, her aesthetic sensibility, her sheer verve and style; all the things that Nixon despised in the patrician, elegantly carefree Kennedys, and self-consciously lacked himself. But the capricious Catholic novelist—who famously declared all fictions to be lies—was not in the business of condemning Nixon’s fibs. The abbess’s polished tyranny notwithstanding, Spark captures an aspect of Watergate so many commentators have missed: Watergate as bungling farce.