We need to talk about neoliberalism—an ugly word with ugly consequences. Consider what happened at P&O Ferries in March. The onboard staff were dispatched like rusting cogs in a creaking machine as the liner turned to a “third party crew provider” to hire more efficient foreign workers—efficiency here defined to mean unencumbered by the UK minimum wage. P&O Ferries confessed to having breached the obligations of redundancy law, but pleaded that this was in the service of an overriding duty—to the bottom line.

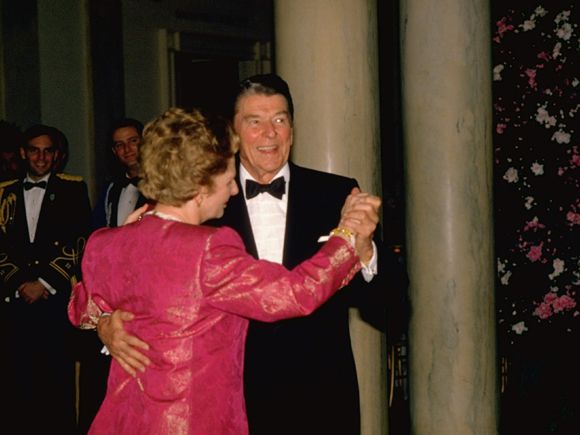

Everyone was in uproar, including members of a Conservative Cabinet who are, to a man and woman, the political children of Margaret Thatcher. Yet this was a tale involving all the impulses she unleashed—the search for solutions in novel markets, the unabashed maximisation of profit and confrontation with the unions—being taken to extremes. Thatcher remains Britain’s most consequential modern leader because these forces, though occasionally softened since she left power, were never fundamentally challenged: a neoliberal order has endured. As Tony Blair, whom the lady once named as her greatest achievement, put it himself: “I always thought my job was to build on some of the things she had done, rather than reverse them.”

On the resurgent right wing of the Labour Party, to acknowledge this remains curiously taboo: “neoliberal” is dismissed as an empty leftist “boo-word.” Fortunately, American liberals are in a more reflective mood, and—as two new books attest—are interrogating the nature of the age we’ve been living through, and are, just possibly, beginning to escape.

Francis Fukuyama is forever doomed to be caricatured as “the end of history” triumphalist. But the starting point for the wonderfully crisp Liberalism and its Discontents is that the basic planks of the liberal way of running things—independent courts, free speech, a plural media—are gravely imperilled. The global index of freedom and rights run by Freedom House has been in decline for 15 continuous years. Fukuyama sees the illiberal backlash as provoked by extreme offshoots of liberalism, one of them being neoliberalism, which has produced “grotesque inequalities” by hardening the traditional liberal presumption of free exchange to the point where “the doctrine becomes, so to speak, doctrinaire.”

Although a man of the left, the Cambridge historian Gary Gerstle is unfailingly curious about the once-wild neoliberal ideas that came in from the cold in the 1970s, and steadily redefined common sense: widening the domain of commerce; curtailing the legitimate reach of the nation state; reducing all understanding of personal human behaviour to “the response to incentives.” Having previously charted the rise and fall of the New Deal dispensation that defined America between the 1930s and 1980, Gerstle knows what a political order involves: a web of rules, institutions, presumptions and people that can survive a change of government. His American focus might also finally allow British readers to escape their factional trenches and appreciate the shape of neoliberalism. It is a terrific service, although I wonder if Gerstle, like Fukuyama, might have concentrated a touch less on the detailed lines of neoliberal thinking, and a touch more on the interests that neoliberalism has served.

Long before the “neo” turn, liberalism was, Fukuyama suggests, occasionally prone to warping into dangerously unfair forms. Locke’s questionable notion of the origins of private property—human effort transforming the “worthless things of nature”—became outright absurd when applied to economies built on colonial conquest. Civil servant Charles Trevelyan looked at the Irish potato famine from the perspective of the Treasury and diagnosed what neoliberals would now call “moral hazard,” writing “the calamity must not be too much mitigated” because the “real evil” was not starvation, but the “turbulent character” of those it befell.

Gerstle, like Fukuyama, places neoliberalism squarely in the liberal tradition. His story begins in 1920s Vienna where economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek were scrambling to recover liberalism’s lost mojo. They disliked the contemporary movement, known confusingly as “new liberalism,” which argued that the old “freedom to” liberties needed supplementing with government action to ensure “freedom from” the deprivations that stifle human agency. In Britain, the new liberal thought of Leonard Hobhouse and JA Hobson was manifested in the welfare reforms of Henry Campbell-Bannerman, HH Asquith and David Lloyd George. In the US, Herbert Croly’s Promise of American Life (1909) inspired Theodore Roosevelt’s progressive movement and anticipated the government-to-the-rescue liberalism later associated with his distant cousin, Franklin.

Mises and Hayek howled in the wilderness against this collectivist turn, which mass enfranchisement, the fear of the working classes turning to communism and the unifying spirit of the Second World War successively entrenched. Hayek, and American fellow travellers such as ex-president Herbert Hoover, sometimes mused on how markets were embedded in society in ways their laissez-faire Victorian forebears had missed. But after the foundational 1947 meeting that Hayek convened at Mont Pelerin, Switzerland—whose 36 attendees included Mises, Milton Friedman and philosopher Karl Popper (who pushed back against the narrowness of the emerging dogma)—the basics were clear. The big neoliberal idea was simply to encourage as much of a market society as modern life and politics would allow.

Mises and Hayek crossed the Atlantic for perches at American universities—Hayek for Chicago, which became a hub of free-market theory. But amid the stable prosperity of the 1950s, they were doomed to remain on the margins. President Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, maintained a top tax rate of over 90 per cent, built infrastructure and, in his own words, sought to “improve and expand our social security programme.” But the neoliberals stuck around. New members of the Mont Pelerin Society had to “pledge their affinity to market-based approaches,” and bided their time, Gerstle notes, as an “exceptionally disciplined and focused network.”

Eventually, opportunity came—on multiple fronts. As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, the New Deal (or in Britain “postwar”) order simultaneously struggled with general inflation, rocketing oil costs, union militancy and the “anti-system” radicalism of the student left. Meanwhile, the big geopolitical picture was dominated by increasingly competitive global goods markets and Soviet stagnation, twin developments that Gerstle regards as reducing the ability and the motive for America’s economic elites to engage in class compromise.

Prod most neoliberal ideas, and it's clear whom they suit

The eventual market deregulation, union-busting and tax-cutting of Reagan is familiar, but Gerstle elegantly rehearses it all. The less familiar part of the story is what happened before and after Reagan. Jimmy Carter’s frustration with cosy but faltering New Deal corporatism drove him to infuse competition into the airline sector and drive through the break-up of the telephone utility, AT&T. An intriguing imp on Carter’s shoulder was the anti-corporate consumer rights champion, Ralph Nader, who led a left backlash against “producer interests” inherent in a New Deal order, in which industry insiders would often help to regulate their own markets.

It isn’t that Carter entirely gave up on tripartite—unions, business, government—initiatives. Intermittently he kept trying, much as his exhausted British counterpart, Jim Callaghan, continued to serve up beer and sandwiches to union leaders at No 10. But when it came to the crunch, just as Callaghan turned to an IMF loan and austerity, Carter appointed anti-inflation hawk Paul Volcker to the Federal Reserve. Volcker’s name became synonymous with his interest rate “shock” and the associated industrial depression.

At the other end of the story we have Bill Clinton, the “Democratic Eisenhower” and the great “facilitator” of the neoliberal high noon. True, the flipside of his individualist economics was a relaxed social “cosmopolitanism,” which inspired Newt Gingrich’s Republicans to turn to culture war and impeachment for his lying about his affair with Monica Lewinsky—so this felt like a time of political war. But he worked snugly with them on the money stuff. Unforgivably, he connived in 1996 welfare “reform” legislation that shredded America’s hardly generous safety net. He signed off on the 1999 move to repeal the post-Wall Street crash Glass-Steagall restrictions that kept different parts of the banking system separate. Within a decade an orgy of financial games had unravelled into crunch, crisis and slump.

Clinton was tacking his sail to the winds of the time: the communist challenge had collapsed. Like Tony Blair, he oversaw some progressive individual moves on tax and the minimum wage. But in the US there was little of the rebuilding of the public realm that Blair presided over in the UK. With soundbites like “the era of big government is over,” Clinton made sure the Reagan revolution would stick. And stick it did, under not only George W Bush but also Barack Obama, who after the 2008 financial meltdown nervously reached for a gang of experienced Clintonians with Wall Street connections to run his economic policy.

What eventually crashed the neoliberal order, as Gerstle sees it, was not any progressive challenge, but the unlikely figure of Donald Trump, who rode into Washington on a tide of rants about immigration and global trade. Although Trump delighted Republican neoliberals with deep corporate tax cuts, Gerstle concludes that his more enduring legacy will be calling time on a consumer-first globalisation which had, by the late 2010s, left the typical American working man without a wage rise in 45 years. With the spell broken, down-at-heel voters won’t dance to the old tunes any time soon. What we get next, Gerstle thinks, is up in the air: it could be more America First chauvinism or a new progressive era. What it won’t be, however, is another round of neoliberalism.

Mostly a joy to read, Gerstle’s is resolutely a book of ideas. At times, though, that focus makes for an over-intellectualised account. He is unduly detained by Reagan and Thatcher calling themselves “conservatives” when their free-market capitalism was so disruptive. He is at pains to understand how the Reaganites could reconcile their libertarian economics with their “neo-Victorian” moralising and mass incarceration of African Americans. He turns to the Darwinian-imperialist Victorian theories of Herbert Spencer and Gertrude Himmelfarb’s right-wing sociology in trying to square such circles.

But shift to thinking about neoliberalism as a politics of interest instead of ideas and these difficulties dissolve. Jailing black people and railing against abortion become merely one means of stitching together a winning coalition for the core programme. Unlike 19th-century liberalism, which really did threaten established landowning elites, neoliberalism has overwhelmingly entrenched wealth, a decidedly conservative function. True, there was also a more benign shift from a producer to a consumer perspective—but that is another rebalancing of interests.

Brute interests explain an awful lot of what the neoliberals did in power. Take Gerstle’s breathtaking retelling of the occupation of Iraq, which highlights the Bush administration’s faith that a vigorous market would spontaneously arise to fill the vacuum created by smashing Saddam’s state, a naive hope aired often in the distinct neoliberal vernacular of the time. But whatever the free-market cant, Iraq’s US-led Coalition Provisional Authority government also “reserved” “big contracts for American firms that, in many cases, were bidding against no one.”

If one neoliberal hallmark has been intricate financial arrangements, another has been elaborate rationalisation of these in terms of reallocating risk. But again, a cruder story of interests is more instructive. That is true both of poor value public-private partnerships such as PFI in the UK and for supposedly purely private wheezes such as the “securitisation” of debt, which were—as Gerstle documents—actively encouraged by governments until they found themselves bailing out the banks.

Prod most neoliberal ideas, and it’s clear whom they suit. Both Gerstle and Fukuyama discuss how the Reaganite lawyer Robert Bork successfully narrowed the focus of anti-monopoly policy from nebulous notions of commercial plurality to a specific test of “consumer welfare” defined purely by price. That suits Amazon fine, but far less (say) local bookshops or the customers who used to enjoy browsing in them. In parallel, economist William Baumol (not mentioned in either book) dreamed up “perfect contestability theory,” which echoes the textbook “perfect competition” ideal but concludes it doesn’t matter how dominant a business grows to be in any market so long as there is potential contest from new entrants. For the neoliberals, the traditional liberal presumption of real competition was trumped by the assumption that governments should keep their hands off business.

While the intriguingly mercurial Hayek and more plodding Friedman loom large in both books, I’d have made room for a British brain that ended up in Chicago. Ronald Coase was a Nobel Prize-winning economist who argued that market failures, such as pollution, could be fixed by allowing everything to be traded after extending private property rights into public goods such as the environment. Because far from being emancipatory, a lot of the neoliberal programme can be thought of—in ways neither Gerstle nor Fukuyama really capture—as akin to the historic enclosures of common land, excluding some in order to strengthen property rights for others. Think of the American intellectual property regime that (prior to a 2013 court ruling) developed to allow 4,300 human genes to be patented as if they were inventions. Or indeed of its European equivalent, not long ago strengthened in the name of “creativity,” to guarantee fees for the great-grandchildren of ageing rockers for decades after their death.

Other audacious “enclosures” have blocked most Britons from watching live football on TV and obliterated awareness of cricket from the young. Artificially constructing barriers to stop non-subscribers enjoying something that would otherwise be shared at no marginal cost is inefficient. But under the neoliberal reign, a restriction that would once have been politically impossible came to be accepted as the way the world is.

Only with a “property first” rather than a “freedom first” reading of neoliberalism can we understand how Mises could hail 1920s fascism as a “makeshift” salvation for civilisation against the left, and grasp why the ageing Hayek would defend the 1970s coup against an elected socialist government in Chile, which brought Pinochet’s murderous regime to power. Yes, ideas had an important role in the neoliberal story. But ultimately it has been an instrumental one.