In this brilliant and stimulating book about the role of Oxford University in producing Boris Johnson and his Tory henchmen and inflicting Brexit and the rest on a beleaguered Britain, FT journalist Simon Kuper indicts the university for these crimes. He pronounces a heavy sentence: the only sure way of preventing similar horrors recurring is for the dreaming spires to stop recruiting undergraduates entirely.

I would appeal against this verdict at the Oxbridge-dominated Supreme Court, for reasons that I will set out later. But whether you agree with it or not, Kuper’s critique of the university as it was in the 1980s, and his blueprint for the future, deserve wide debate.

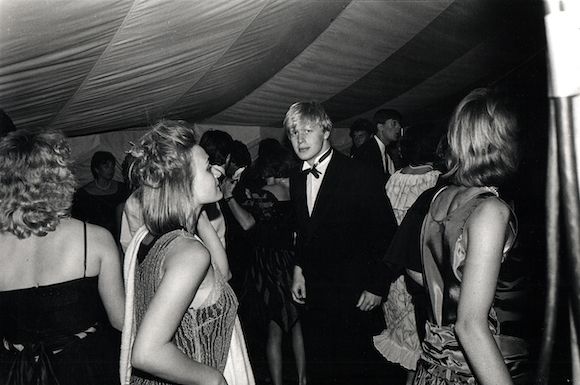

Kuper, who attended Oxford in the 1980s himself, argues that what he calls the “Oxocracy” produced the “Tory Brexiteer subgroup,” which “ended up making Brexit and remaking the UK.” This subgroup is malignant and needs to be eradicated. On this point, he is obviously right that a group of Tories who attended Oxford in the 1980s, led by Johnson and including Michael Gove, Dominic Cummings, Daniel Hannan and Jacob Rees-Mogg, were largely responsible for the passage of Brexit in the 2016 referendum and since. Crucially, most of Kuper’s “chums” were also at public schools before Oxford. Even Gove, adopted at the age of four months, went to Robert Gordon’s College, a private school in Aberdeen.

Kuper is in fact analysing a part of the 1980s umbilical cord between Oxford and elite private schools, particularly Eton. His focus is on the subset of that group which climbed the greasy pole of the Oxford Union debating society, where they learned to play the student game of thrones now being imposed on the country at large.

Given the centrality of Eton to the story—attended by both Johnson and David Cameron, whom he displaced over Brexit—the Oxocracy of the 1980s might better be called the “Etocracy.” Eton’s motto—Floreat Etona (Let Eton Flourish)—has been pretty well a command to the Tory Party, five of whose 12 leaders since Churchill were educated there. Johnson and Cameron were at one with William Waldegrave, aristocratic Old Etonian and a minister during the Major period, who writes in his recent memoir: “ever since I could remember, one consciously constructed goal [to become prime minister] had been the magnetic pole around which everything I did was centred.”

Johnson is this generation’s “Prime Etonian” more than its “Prime Oxonian.” As I argued in my Prospect profile of him in Summer 2021, Johnson was part created and part curated by Eton, which was far more significant to his character development than Oxford. I wrote then that Johnson “is a classic Eton type: a bright boy from a thrusting Tory family—father Stanley a minor public school (Sherborne) Tory MEP of exotic international pedigree.”

Johnson proceeded from a feeder prep school to one of the 70 King’s scholarships at Eton, then to Balliol College, Oxford, the presidency of the Oxford Union, and into journalism as a route to becoming a Tory MP.

It does not vitiate Kuper’s argument that Brexit took place because of a split between two Oxford Tory Party leaders of the 2010s. Nor that had David Cameron played his hand better, or Johnson planned his leadership ambitions slightly differently, Brexit may not have even happened. In fact, that Johnson played so casually for such high stakes precisely fits Kuper’s argument about the evils of Oxocracy. Brexit became the topic of an Oxford Union debate where they could take either side. As we now know, Johnson actually wrote essays for both sides of the Brexit debate, as draft Telegraph articles, before deciding which way to plump in 2016.

The most biting element of the story Kuper tells is therefore about the evils of Oxocracy and Etocracy combined as a system of English elite formation. His argument fits the 1980s, but not the present day, where Oxford recruitment is shifting rapidly from private to state schools. The colleges have a far broader social reach and far less entitled mien, and the university itself is radically different and more professional than a generation ago.

I spent almost the entire 1980s at Oxford, first as an undergraduate, then doctoral student and college fellow. The public schoolboys and girls undoubtedly set the tone for the undergraduate phase. They comprised far more than half the intake and dominated clubs, societies and elite sports. It is true too that the “Union set” attracted a profile wholly disproportionate to its tiny number of attendees, as Kuper attests from consulting the university student newspaper Cherwell.

As a Keble undergraduate, I barely attended the Union and neither did most Labour, SDP and Liberal students, regarding “Union hacks” as ludicrous social poseurs. However, Johnson’s initial defeat in the race for Union president came at the hands of a grammar school Liberal, Neil Sherlock; and second time around, when he won, he was backed by an SDP faction proposing to break the old two-party system. It is a quaint thought that if more of us had piled into the Union for the vote that day, the political history of the last three decades might have been different.

The real point is that Johnson has spent his whole life seizing the main chance with whatever policies were to hand. Had the left and centre been stronger politically across recent decades, he and his chums would have drifted there; and even if the Etocracy hadn’t made him less prominent, it would have made him less populist and right wing—witness his eight years as mayor of London, where he largely continued Ken Livingstone’s agenda because it was the only way he could win.

In his politics, as in his journalism for the Spectator and the Telegraph, Johnson went with the tide while becoming the wave. But the real evil genius of Brexit, Nigel Farage, didn’t go to any university, let alone Oxford: he was a Dulwich public school rebel who went straight into the City as a wide-boy metal trader and then made himself a tribune of English nationalism through Ukip.

The tale of Brexit is largely the story not of Oxford, but of Farage’s reverse takeover of the Tory grassroots. He became an MEP thanks to the Blair government’s introduction of proportional representation for European elections in 1999—a reform originally expected to benefit Paddy Ashdown’s Liberal Democrats. Farage operated in parallel with a mega-rich maverick, James Goldsmith, and an initially small group of Thatcher-inspired Tory MPs led by Bill Cash, Iain Duncan Smith and the other “Maastricht rebels” of the early 1990s. None of these groups included Johnson and chums, even after his arrival in the Commons in 2001. As mayor of London, he was a champion of the EU’s single market, of real importance to the City.

It is vital therefore to understand how contingent Oxford was in facilitating a path to Johnson and Brexit.

As for turning Oxford into a graduate-only university, it is a substantial part of the way there already. Oxford now has more postgraduates than undergraduates, whereas a generation ago there were only a third as many postgraduates. The university has come top of the Times Higher Education world university rankings for the sixth consecutive year. It boasts global leadership in many disciplines, including medicine and the sciences, and its leaders are preoccupied with expanding the graduate side further still—including new postgraduate colleges for science and engineering.

Oxford is now largely a research university, and its current public profile has little to do with its Oxford Union hacks but rather AstraZeneca vaccine heroes like Sarah Gilbert, who was last year’s BBC Dimbleby lecturer on the subject of “Vaccine vs the Virus: This Race, and the Next One.” Her concluding words could not be further from Kuper’s chums: “as we turn our attention back to climate change, poverty, war and other problems that never went away, what we discovered was what we can do when we understand our goal, and really put our minds to achieving it.”

Equally important is the dramatic decline of Etocracy and the weakening of the link between the public schools and Oxbridge in undergraduate admissions. The number of Etonians at Oxford has halved in the last generation, and the private school proportion is now down to 30 per cent, from 42 per cent just six years ago. It will continue to decline as higher-achieving state academies, and more egalitarian Oxford tutors and heads of colleges, continue to boost state school recruitment. Mansfield became the first college to recruit more than 90 per cent of its students from state schools, and others are following suit. Lady Margaret Hall, led until last year by Prospect editor Alan Rusbridger, has pioneered new access programmes. The remedy for Kuper’s Oxocracy is being implemented.

Nor is it, in my view, a good idea for Oxford to become graduate-only for purely academic reasons. A university ought to be as much about teaching as research, and it is a great thing for the social and political leaders of tomorrow to be exposed to the academic leaders of today. Unlike Germany and many other European countries, the UK has a tradition of elite boarding universities and a well-established pecking order. If Oxford unilaterally stopped recruiting undergraduates, the best-qualified school leavers would simply cascade down the Russell Group and to universities abroad.

Kuper’s key insight is that Oxford in the 1980s was barely connected to the broader society in which it operated, causing huge damage to that society and to Oxford itself. A graduate-only Oxford and Cambridge, in which UK students and dons were a minority among a largely international student body, would suffer from a different but equally lethal crisis of social disconnection. A university with more students from China than Britain, and whole disciplines with only a handful of Brits as professors and doctoral students, is a recipe for an anti-Oxford critique far more potent than the problem of Balliol College and the Oxford Union that produced Boris Johnson 35 years ago.

In place of Kuper’s plan, I would instead introduce a different “levelling-up” reform challenge for Oxford. It needs to radically broaden the social intake of its state school recruitment, which today is too largely drawn from grammar schools, sixth-form colleges and academies in London and the southeast. According to the Sutton Trust, nearly half of all state schools in England send an average of less than one student to Oxford or Cambridge in a typical year. Greater equity between different kinds of state school in Oxbridge recruitment should be the agenda for the mid-2020s, not just the state-private balance.

The old public-school tone and culture of Oxford now has more in common with Jeeves and Wooster than Jesus and Worcester. Kuper has hammered another nail in its coffin, but Oxford itself has undertaken most of the transformation already. Rather than constrain its growth artificially, we should let it flourish in its new guise.