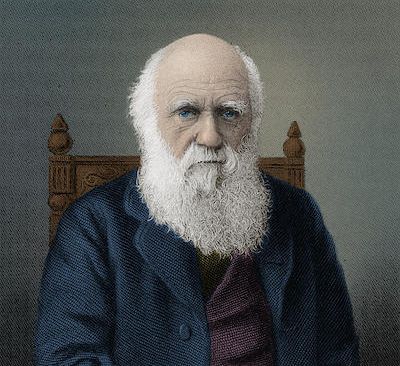

Towards the end of his life, Charles Darwin looked back with sadness at what he felt he had lost. In a short autobiography, intended only for close family members, he contemplated how in his early years he “had strong and diversified tastes.” Some of these tastes were scientific, but many were not. He sat for hours reading Shakespeare, Byron, Scott, Milton, Gray, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Shelley, while art and music also afforded him, he wrote, “very great delight.”

From around the age of 30, however, as his scientific research progressed, Darwin began to lose all pleasure in poetry: “I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me.” It was a similar story for art and music. Darwin lamented that “my mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts,” before wondering, “why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive.”

Iain McGilchrist might have been able to help him. McGilchrist rose to intellectual fame with his 2009 book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Across 600 or so pages, he argued that there was a significant difference between the brain’s left and right hemispheres—a difference so important it could help to explain the history of western civilisation.

Western culture, he claimed, has oscillated between left- and right-hemispheric approaches to the world—the former emphasising order, control, rationality, agency and bureaucracy, and the latter experience, change, empathy, freedom and openness.

In the metaphor of the book’s title, the right hemisphere’s broader perspective should make it the master with the left performing the (indispensable) role of emissary, bringing the necessary information and executing the right hemisphere’s instructions. However, over the last 200 years, we have first understood— and then remade—the world in the mechanistic image favoured by the left hemisphere. The result is that the emissary has become the master.

“Left brain-right brain” discourse has not, in general, had a good press—and with some justification. The brain is a bewilderingly complex organ and our tools for understanding it are blunt and inadequate. Almost any statement you make about the brain can be contradicted with a counter- example. Pop-neuroscience has simplified the thesis into a kind of “left brain is from Mars, right brain is from Venus” narrative—the caricature that “left-brain people” are geeky scientists and “right-brain people” are dreamy artists—which is at best misleading, at worst simply wrong.

McGilchrist’s take was altogether more sophisticated. As he writes in The Matter with Things—the two-volume follow-up to The Master and his Emissary—“just about everything that is said about the hemispheres in pop psychology is wrong because it rests on beliefs about what the hemispheres do, not about how they approach it.”

As McGilchrist is at pains to repeat in his new book, both hemispheres are involved in more or less everything. It’s not so much that there is a strict division of responsibilities—although some faculties do reside in one half rather than the other, like language in the left side—so much as a division of style. The two hemispheres do things in different ways.

There is an evolutionary way of explaining this. All creatures need to do two things: first, to get things such as food or material for shelter; and second, to avoid being got by other things such as predators. The first of these demands intensely focused attention on whatever has already been identified as important. If you want to catch fast-moving prey, you need to deploy all your mental energies on your target. The left hemisphere is very good at doing this. The second demands vigilant and sustained attention to everything that might make a meal of you. This kind of attention, in which the right hemisphere excels, doesn’t already know what is important. Its job is to discern what might be significant in the world—as it were, to keep an open mind.

To master both necessary and interdependent skills, evolution found a counter-intuitive solution: “two neuronal masses, separate enough to function independently, but connected enough to work in concert with one another, each capable of sustaining consciousness on its own.” It’s counter-intuitive because the brain achieves its remarkable powers by means of connections: why reduce that connectivity by splitting the whole thing in two?

Yet this is how the brain works—something very widely attested in scientific literature. McGilchrist points out that asymmetries of brain and behaviour can be traced back more than 500m years, and are even present in ultra-simple creatures such as the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, whose nervous system comprises only 302 neurons. As far as humans are concerned, the consequence is that we engage with the world in different ways depending on whether we are drawing more on the left or the right hemisphere.

This is the moment at which the story risks sliding into caricature, so it is worth emphasising how rigorous, wide-ranging and well-evidenced McGilchrist’s work is. Initially studying English at Oxford, he was awarded a Prize Fellowship at All Souls (twice re-elected), where he taught literature and philosophy. (His first book, Against Criticism, argued against the “destructive analytic tendency of criticism” in favour of art’s ability to “create new wholes.”) Then he switched to medicine, later becoming a research fellow in neuroimaging at Johns Hopkins University Medical School in the US. Adding another string to his bow, he is also a fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Like Darwin, the young McGilchrist had strong and diversified tastes. Unlike Darwin, he has retained them.

His polymathic mind is on full display in The Matter with Things. Clocking in at nearly 1,600 pages (including a 200-page bibliography) and with over 5,000 footnotes, it is an extraordinary achievement, beautifully produced by the small publisher Perspectiva Press, clearly written and peppered with good-quality illustrations. Although expensive at £89.95, it is not that expensive in comparison with many academic books.

It is divided into three roughly equal parts of about 400 pages each. The first, “The Hemispheres and the Means to Truth,” comprises nine chapters on how the two sides of the brain operate differently. His argument is based on impeccably documented neurological evidence. It is now possible to study in detail patients who have lesions impairing the activity of one hemisphere and patients who have experienced a hemispherectomy, in which half the brain is disconnected or removed. It is also possible to temporarily suppress the activity of one half of the brain in healthy patients; to look at blood flow and electrical activity across the brain during certain exercises; and to examine patients with schizophrenia and autism. Conclusions are necessarily partial and tentative, but over the years an overwhelming body of evidence has built up showing that the two hemispheres of the brain do indeed engage with the world in different ways.

The research shows that the left hemisphere is less aware of its surroundings and tends to ignore what is irrelevant to its purpose: it sees clearly, but it sees little. Inclined to “either/or” thinking, it enables us to manipulate the world. It reacts faster than the right side, at least when the nature of the task is known. It is optimistic, purposive, precise, certain and confident—even when it gets things wrong. The right hemisphere, by contrast, is better at understanding the world in all its complexity. It is inclined to “both/and” thinking and more willing to change its view in the light of new evidence. It is reflective, empathic, exploratory, more uncertain and self-deprecatory than the left hemisphere.

The left hemisphere is better at “how” and “what,” while the right is better at “why”—though McGilchrist points out that both are capable of addressing either set of inquiries depending on context. The left sees constituent pieces, whereas the right sees the whole. The left explains, the right understands. The left apprehends, the right comprehends. Perhaps most importantly, the right hemisphere is present in the world—acutely aware of its surroundings—whereas the left is prone to represent (literally re-present) it—preferring, as it were, the map to the territory.

This is all very interesting, but McGilchrist’s real genius has been to see its wider implications. In parts two and three of The Matter with Things, he applies the underlying hemispheric analysis to the fundamentals of thought and reality. Part two centres on epistemology—how we can come to know anything of the truth—and speaks to a culture in which reason and science are judged as the only trustworthy paths to genuine understanding.

Even writing that sentence feels risky, inviting the accusation you are undermining reason and science in favour of… what? Authority? Rumour? QAnon? McGilchrist, of course, does no such thing. He defends reason and science as vigorously as anyone, but argues that both are laden with creative assumptions, beliefs, metaphors, values and moments of inspiration, while insisting that neither is sufficient on its own. The roads to truth are more varied than arch-rationalists admit. In the words of the physicist Max Planck, whom McGilchrist quotes: “anybody who has been seriously engaged in scientific work of any kind realises that over the entrance to the gates of the temple of science are written the words, Ye must have faith. It is a quality which the scientists cannot dispense with.”

And not only scientists. Some of the most enjoyable passages here are when McGilchrist engages with readers of The Master and His Emissary, who tell him how the book helped explain their own behaviour. There aren’t many works of neuroscientific philosophy that include the thoughts of a racehorse trainer-turned-tipster or a medical consultant who looks after competitors in the Isle of Man’s terrifying TT road race. But their fascinating observations on how they pick winners or how speeding motorcyclists navigate treacherous roads confirm how we arrive at the truth through more than algorithmic reasoning. We must integrate imagination and intuition as well as “the experience of the whole embodied person.” Both hemispheres are needed to discern reality.

At this point there is a dangerous hole down which the argument risks slipping. McGilchrist is not proposing that the brain creates its own reality by means of the different ways it attends to the world. We do not generate our own truths and the world is not wholly dependent on the mind. But nor is it wholly independent of it. Rather, as Wittgenstein observed, we see reality “as” something, not simply interpreting all sense data raw but doing so in the forms and patterns we are primed to recognise. The way we look at it informs what we see. Better still, in Wordsworth’s words from “Tintern Abbey,” a favourite poem of McGilchrist’s, our senses “half create, / And… perceive” what is before us. Or, as McGilchrist puts it, “all human reality is an act of co-creation.”

Which makes it a problem if, as McGilchrist argues, we have come to see the world too much through the left hemisphere’s perspective. For the left brain is “relatively uncomplicated by issues of beauty and morality, and relatively untroubled by the complexity of empathy, emotion and human significance.” By contrast, in a world seen by the right hemisphere, “nothing is clearly ever the same as anything else. All is flowing and changing, provisional, and complexly interconnected with everything else… everything needs to be understood in context.”

McGilchrist’s terms are conspicuously close to Darwin’s. The machine, McGilchrist writes, is the model favoured by the left hemisphere. It has become the image through which we understand—and in which we increasingly make—our world. By contrast, McGilchrist insists that “the most fundamental truths… can ultimately be expressed only in terms of poetry,” a capacity that, like Darwin, we are in danger of losing.

Seen through the lens of the dominant, overconfident left hemisphere, ideas such as consciousness, value, purpose and the sacred are broken down, picked apart and shown to be illusory. But when the whole brain is integrated with the whole body, they are reality. “I see value as intrinsic to the universe,” McGilchrist writes, “and the possibility of appreciating and responding to value… as one reason for the cosmos having evolved life.” Reductive materialism is an “impoverished philosophy.” The sacred is as real as the material.

Such claims may turn modern ultra-Darwinists purple, but they cannot easily be dismissed. Moreover, McGilchrist’s argument is one with which the elderly Darwin, lamenting his by-now ineradicably Gradgrindian mind, might have had some sympathy. After all, it was precisely Darwin’s strong and diverse tastes that enabled the imaginative leap required to develop the theory of evolution that made him famous. Poetry, music, art and landscape are holloways to truth, deep-sunk into the human mind. “If I had my life to live over again,” Darwin resolved, “I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied could thus have been kept active through use.” It’s good advice to us all.