Karl Marx had plenty to say about the contradictions of mid-19th century industrial capitalism, but he failed to grasp its capacity for reinvention. Certainly he never predicted the rise of venture capital, arguably the most important financial innovation of the last 50 years.

Venture capitalists are a special breed. They finance the most dynamic companies and generate disproportionate amounts of research and development. As a group, they are an intricate part of the networks that power the knowledge economy. Their influence far outweighs their numbers.

VC has produced trillion-dollar winners such as Amazon, Apple, Google and Tesla. Founder-titans like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have built global companies and earned fabulous wealth, enough to indulge their dreams of space travel and flying cars. Once largely the preserve of Silicon Valley, venture capital has gone global, with US offshoots and rival firms in London, Beijing, Berlin, Moscow, Mumbai and Shanghai.

The explosion of VC is partly explained by investors’ hunt for yield in a world economy addicted to low interest rates since the 2008 financial crisis. It has also been driven by the information technology revolution, with its promise of spectacular financial gains. As an alternative asset class, VC has produced returns far superior to equities or bonds. Its high-risk, high-reward model appeals to the most visceral instinct among investors, at least those fortunate enough to enjoy access to start-up companies: the desire to shoot for the jackpot.

There is, of course, a twist. As a rule, the best investment in a venture capital fund equals or outperforms the rest of the fund. Sebastian Mallaby calls this phenomenon “the power law,” a suitably weighty term that serves as the title for his new book. To adopt a baseball analogy, the VC business relies not just on a home run but a grand slam—an outsized return which, he argues, owes more to skill than good fortune.

Venture capital is above all a bet on future potential. Whereas most financiers work out the value of companies by projecting their cash flows, venture capitalists back promising start-ups before they have cash flow to analyse. They take small stakes in companies and hold them in the hope of substantial reward. “Venture capitalists,” notes Mallaby, “look for radical departures from the past.”

Over the last five years, the world has witnessed the equivalent of an arms race, with VC funds mobilising tens of billions of dollars in a bid to gain “first-mover” advantage on behalf of their favoured companies, mostly operating in the high-tech space. The subsequent splurges have led to spectacular crashes for firms such as WeWork, the office-leasing business, and Greensill, the fintech upstart which employed (and handsomely rewarded) former prime minister David Cameron.

Mallaby, an astute chronicler of modern capitalism who has written a biography of former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and a well-received book on the hedge fund industry, addresses these failings, which turn as much on the super-sized egos of founders as nitty-gritty matters of governance. He also tackles, albeit briefly, more delicate issues such as the preponderance of pale, male and stale men at the top of the VC business and whether these rainmakers are better at enriching themselves than at developing socially useful businesses.

For now, any assessment of the impact of venture capital depends on an understanding of its origins in Silicon Valley, with its mix of left-liberal and libertarian politics, whose distinguishing genius, in Mallaby’s words, is that “the patina of the counterculture combines with a frank lust for riches.” It is here, in what has been called “the little kingdom,” where the grass and flowers grow taller than the towers and ambition knows no bounds, that the story of venture capital begins.

Most histories trace Silicon Valley’s roots back to 1951, when Fred Terman, the engineering dean at Stanford, created the university’s research park. An alternative version begins five years later when William Shockley, the father of the semiconductor, left the east coast and founded a company on Terman’s campus.

Mallaby identifies a third decisive moment—in the summer of 1957—when eight of Shockley’s PhD researchers grew tired of his heavy-handed leadership and walked out. “It was that act of defection that created the magic culture of the Valley, shattering traditional assumptions about hierarchy and authority and working loyally for decades until you retired with a gold watch.”

The technology team’s exit en masse was encouraged by a new form of finance, dubbed “adventure capital.” This was very different from a bank loan with its promise of an early, modest return secured against collateral such as a house. Adventure capital, later shortened to “venture capital,” was a bet on a mouth-watering payout based on a breakthrough invention, in this case via the team’s new company called Fairchild Semiconductor.

A quiet revolution followed. Among the most important innovations was the combination of multiple transistors in one tiny integrated circuit, a technological breakthrough with massive civil and military applications. Another was the introduction of stock options and the growth of an “equity culture” among the venture capitalists’ general partners, the entrepreneurs and their employees. Above all, the next two decades saw the rise of “clusters,” or networks, based on risk capital and scientific innovation aimed squarely at the market.

Mallaby reminds us that once VC had achieved “escape velocity,” the US government also made decisive interventions. In the Carter-Reagan years, Congress progressively cut capital gains tax and later relaxed its prudent-man rule, which previously restricted pension funds in their choice of financial managers, thereby opening the way for them to invest in high-risk assets.

(Memo to Chancellor Rishi Sunak: the timing and nature of government intervention is critical, as explained at the end of Mallaby’s book. Tax breaks work better than direct subsidies because they create healthier incentives. The liberal provision of visas to foreign scientists and entrepreneurs matters more than misguided government support for venture capital, exemplified by China’s spendthrift “guidance funds.” Above all, focus on incentives for the employees of start-ups.)

Mallaby writes with humour and historical sweep, though he lacks Marx’s ability to produce the memorable aphorism. His account is immensely enriched by interviews with most if not all of the rainmakers in venture capital, many of whom came from modest backgrounds far removed from the white shoe brigade on Wall Street.

Three of the founding fathers came from New York state: Arthur Rock, the child of Yiddish-speaking immigrants who grew up poor in Rochester; Don Valentine, the legendary force behind Sequoia Capital whose father was a trucker in Yonkers and a minor functionary in the Teamsters Union; and Tom Perkins, a child of the Depression who had grown up in White Plains on “Spam, margarine, Wonder Bread, and lime Jell-O” and whose fascination with electronics took him to MIT, Harvard Business School and later to Hewlett-Packard as general manager of their computer division in California.

What these men—and they invariably were men in those early days—had in common was a sense of the Next Big Thing, the “moonshot,” which not only marked a technological breakthrough but would also bring stellar rewards, with a payback amounting to five times, 10 times or a multiple even higher. This in turn required an ability to mentor and manage (venture capitalists often sat on company boards) as well as strategic patience, as any decision to exit too early would mean leaving millions on the table.

In the venture capital game, the winner really does take all

The embodiment of these multiple skills was the dapper, bespectacled Michael Moritz. Born in Cardiff to Jewish parents who fled Nazi Germany, Moritz emerges as an unlikely hero in the book. He arrived in the US as an Oxford history graduate and later worked as a reporter for Time magazine, where he covered Silicon Valley, and wrote a book on Steve Jobs and his fabled return to Apple.

In 1986, Moritz joined Sequoia. He had no engineering or managerial background, but he had an immigrant’s hunger and an instinct for lateral thinking. One smash hit followed another: Yahoo, Google, PayPal and many more, all of which ensured that Sequoia would ride the 2001 dotcom crash and grow even more powerful thereafter.

Working alongside co-head Doug Leone—another immigrant, this time from Italy—Moritz epitomised venture capital’s capacity for dynamic re-invention. He was an admirer of Alex Ferguson, Manchester United’s most successful manager, similarly nurturing homegrown talent and purging underperformers in his relentless pursuit of excellence. Yet even Moritz was caught on the hop by another game-changing shift around the turn of the century, this time in the balance of power between VC funders and company founders. Mallaby describes this as “the Valley’s Youth Revolt.”

The first ominous sign was the way Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin played hardball with the venture capitalists over the allocation of equity and their insistence on a dual-class structure preserving their control. The second was their (initial) opposition to Moritz’s advice to hand over operational management of the company to an outside CEO (Eric Schmidt). Despite their technical brilliance, these 20-something software engineers were not best placed to monetise their search-based product, though they did come up with one of the crispest mission statements of all time: “we deliver the world’s information in one click.”

By far the most deliberate snub of the established order came towards the end of 2004, when an even younger entrepreneur, a Harvard sophomore named Mark Zuckerberg, turned up in pyjamas at Sequoia’s headquarters in Menlo Park. Zuckerberg’s nonchalance epitomised “Founder’s Syndrome”: the notion that the founder knows best, needs no checks and balances, and considers the enterprise to be their company rather than controlled by the shareholders. This foreshadowed trouble at Facebook, with its “move fast and break things” mentality; but it also anticipated future blow-ups at Uber and WeWork along with the fiasco at Theranos, the blood-testing company whose founder Elizabeth Holmes was convicted of defrauding investors at the start of this year.

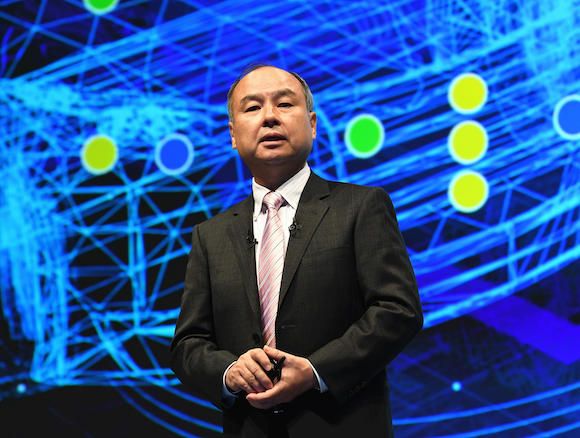

The second challenge to Silicon Valley’s pre-eminence in the VC business came in the shape of the softly-spoken Masayoshi Son, who once described himself as 80 per cent Japanese, 10 per cent Korean and 10 per cent American (born and raised in Japan, he is an ethnic Korean and studied at UC Berkeley). As founder of SoftBank, Son served notice of his ambitions by making two spectacularly successful early bets, first on Yahoo and later on Alibaba, the Chinese internet giant. (He staked $100m on Yahoo—an unprecedented sum of money. His initial purchase of a 25 per cent stake in Alibaba in 2000—for a mere $20m—turned into a long-term investment worth around $150bn.)

By 2016, Son had assembled an even bigger war chest, extracting $60bn out of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi as a part of a new $98.6bn SoftBank Vision Fund. Mallaby describes Son as a “maverick” wandering around with a fat hose, spraying money at targets and distorting valuations to the point where he risked bringing the whole house down. He quotes a damning memo from Moritz to colleagues: “There is at least one difference between Kim Jong-un and Masayoshi Son. The former has ICBMs [intercontinental ballistic missiles] that he lobs in the air while the latter doesn’t hesitate to use his new arsenal to obliterate the hard-earned returns of venture and growth equity firms.”

Mallaby is obviously sympathetic to Moritz. But from Son’s point of view, the world may have looked rather different. He was the disruptor determined to play by other rules. He had bet early on the internet, via Yahoo and Alibaba, and he had been vindicated. Moreover, he had discovered another version of the power law: that, as Mallaby puts it, tech-focused venture portfolios “are founded upon technologies that may themselves progress exponentially.” In this game of “blitzscaling,” the winner really does take all.

On occasions, Son’s faith in founders was badly misplaced. WeWork’s Adam Neumann, memorably captured by Mallaby as “a six-foot-five-inch former Israeli naval officer with hair like Tarzan,” is perhaps the most notorious example. Neumann claimed to be selling the future of work, whereas he was doing little more than leasing office space. Thanks to SoftBank money, WeWork’s valuation hit $47bn before crashing after he was forced to pull an initial public offering. Left unsaid is that Son appointed one of his top lieutenants to sort out the mess. He also pledged $3bn to help fund Neumann’s lucrative exit package before reneging as Covid-19 ravaged the world economy. WeWork went public in 2021, albeit at an 80 per cent discount to its value in 2019.

In his concluding chapters, Mallaby acknowledges that governance at “unicorns”—fabled companies promising valuations of more than $1bn—is broken. But venture capital, he insists, is not to blame. The culprit is “late-stage” money: the mutual funds, hedge funds and sovereign wealth funds who arrived late to the party fuelled by cheap capital provided by central banks. “The financial climate promoted irresponsibility,” says Mallaby.

This paints only half the picture. Arguably, the bigger challenge facing modern capitalism is the decline of public markets. At the end of September 2021, just over 2,000 companies were trading on the London Stock Exchange, down from 2,428 in 2000. Overall, the number of companies listed in the UK has fallen by 50 per cent in the last 45 years. The same is true in the US. There were 7,428 companies listed in the US in 1997; by 2019, that number had dropped to 4,400, partly as a result of a near 50 per cent drop in new listings.

Companies, especially fast-growing ones in need of capital, are staying private longer. Series A funding has extended to Series D and E, with the benefits extended in turn to privileged insiders primarily from the VC industry. These benefits have increased sharply because of the trend towards investing in “growth equity”—companies that are not so much start-ups but more mature actors, whose fortunes can be transformed by an injection of Masa Son-style rocket fuel.

At the same time, increased competition in the market for start-up financing is forcing venture capital to re-examine its own business model. Sequoia recently abandoned the traditional fund structure and 10-year timelines for returning capital to investors. The move allows the firm to retain its holdings in companies well after they go public in a single, permanent structure. It is a big shift, which the firm believes will boost returns and increase the flexibility to invest in non-traditional assets outside of private markets.

VC investors, such as pension funds or university endowments, had little choice but to go along with Sequoia’s decision—even if the terms of trade had fundamentally changed. The move demonstrated once again a capacity for re-invention, but it also underlined how venture capital and private equity are increasingly calling the shots at the expense of established public companies, worn down by tick-box compliance rules and fund managers chasing quarterly earnings.

In the last resort, Mallaby concludes, there are myriad problems venture capital will not fix, and some it may exacerbate, such as inequality. But the answer is not to clamp down on VC. “It is to tax the lucky people who have prospered fabulously over the past generation—including those who made fortunes as venture capitalists.”