A picture that once was worth a thousand words may now seem opaque, yet with a little historical explanation remain illuminating several centuries later. Scientific caricatures were designed to make people laugh but also to think—and they can still do that. Although often overlooked by academics, these visual satires collectively altered how society perceived the effects of science, technology and medicine. And that matters, because attitudes of the past influenced how we reached the present and what we think today.

As historical documents, these images need to be considered in the context of their time, but they resist being classified into neat groups. In his mission statement displayed at the entrance to London’s Cartoon Museum, Steve Bell writes that caricatures are united by their diversity: “they stand alone, autonomous, defying even rudimentary categorisation.” They do, however, share a second quality: once you understand them, they can be very funny and very sharp-edged. Often complex as well as witty, caricatures provide an entertaining lens for historical detectives examining the past. They can also display contemporary reactions to scientific and technological innovations, although some of them express attitudes that nowadays seem disturbingly offensive.

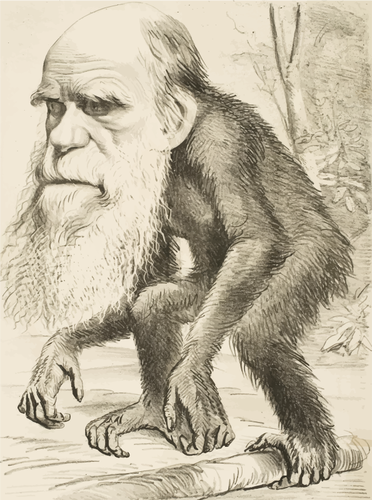

During the 19th century, one scientist above all others gained instant recognition—Charles Darwin. His face was a gift to the lampoonists, since his domed forehead, long beard and beetling eyebrows required little exaggeration to convert him into an ape with long, hairy arms and prehensile feet. Far from being offended, Darwin loved the publicity these drawings brought and built up his own private collection; proudly showing “A Venerable Orang-Outang” to a visitor, he remarked that “The head is cleverly done, but… too much chest; it couldn’t be like that.”

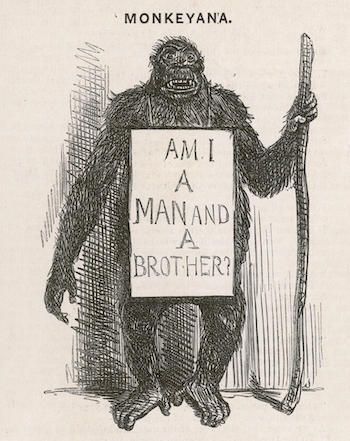

When Darwin published his controversial book On the Origin of Species (1859), he was too scared to discuss human beings, but readers drew their own conclusions and were often appalled at his theory’s implications. Darwin, despite his willingness to be the butt of the joke, might have been troubled by the vicious satires that were widely distributed in the press, which carried sinister messages consolidating existing prejudices. Among the first to appear was Monkeyana, which had been inspired by an explorer’s romanticised confrontations with African gorillas. In that example, a threatening simian’s placard evocatively omits a crucial word from the famous abolitionist slogan, “Am I not a man and a brother?” that had been devised by Darwin’s grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood. Even cartoons with no explicitly scientific references portrayed Irish rebels with distorted ape-like features and grimacing teeth: science and racism reinforced each other.

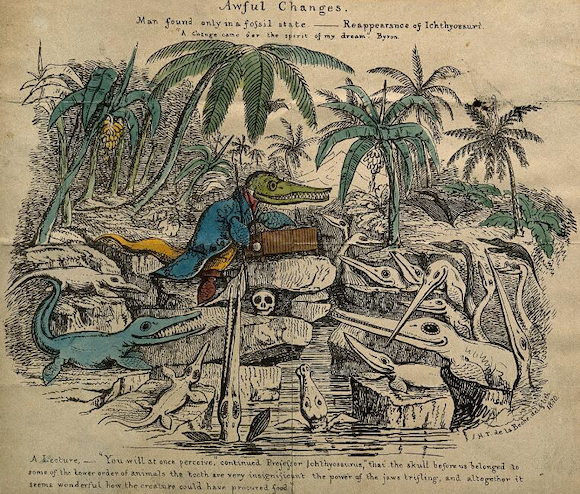

My personal favourite from the 19th century pokes fun at one of Darwin’s close friends, the geologist Charles Lyell, who tried to accommodate mysterious fossils within an expanded timescale for the earth’s history. Lyell argued that we live in a universe characterised by slow uniform change, but he also suggested that it operated cyclically. When he explained that extinct creatures could in principle re-emerge, he whimsically conjectured that: “The huge iguanodon might reappear in the woods, and the ichthyosaur in the sea, while the pterodactyle might flit again through umbrageous groves of tree-ferns.”

In response, a rival palaeontologist promptly circulated a playful lampoon round the scientific community. Although appearing to show a prehistoric school for reptiles, it was intended to depict the far-distant future. Short-sighted Lyell is immediately identifiable as Professor Ichthyosaurus by the tinted spectacles perched on his snout, which show him the world how he wants to see it, not as it actually is. Teaching his students about a fossilised human skull, he insists that it belongs to an inferior creature: “the teeth are very insignificant, the power of the jaws trifling, and altogether it seems wonderful how the creature could have procured food.” The erudite professor was judging the extinct species homo sapiens in terms of his own physical makeup, rather than on human requirements for survival.

Despite the mockery, the basic principles of Darwin’s theory of evolution and the less sensational elements of Lyell’s uniformitarian theory were absorbed into modern science. In contrast, other sciences were deemed legitimate for a time but later rejected. These included phrenology—how bumps on the skull are related to mental traits—and physiognomy, which explored the links between appearance and personality, often associating obesity, disability or senility with lack of virtue. Echoing Carl Linnaeus’s success in classifying plants and animals, adepts hoped to impose taxonomic order on human variety by creating recognisable types. Although their theories were discarded, traces still remain—a large forehead, for example, is often said to indicate a brainy person, while a long, sharp nose indicates a sly politician.

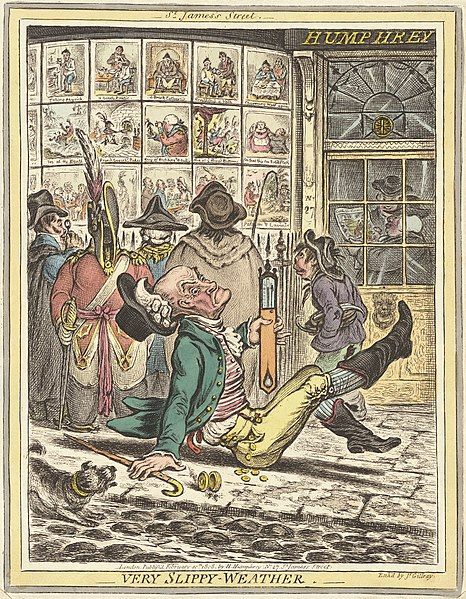

Such scientific topics fascinated James Gillray, England’s most famous caricaturist. Before steam printing slashed prices and made mass publishing possible, illustrators created expensive individual engravings that were printed in black and white, but could subsequently be coloured by hand, often by women working at home and paid rock-bottom rates. These engravings helped to mould public opinion because even people with little money clustered round shop fronts, annoying genuine customers by blocking the street. Wealthy purchasers bought caricatures to impress their friends and decorate their walls, although regrettably Victorian modernisers painted over many of them. Others fell victim to censorship: a collection of Gillray’s sexual images was suppressed during the 1840s, but eventually reappeared in a bin liner during a clear out at the Ministry of Justice in 2009.

Gillray’s Slippy Weather, an ostensibly slapstick banana-skin joke, is packed with phrenological commentary. An elderly gentleman has fallen physically because he is morally decadent. His scientific instrument—a strategically placed thermometer—has proved useless, while his coins and snuff box are rolling away, his wig has flown off and his braces have snapped so that his trousers will descend. Evidently originating from the higher social ranks, he now lies lower than the impoverished ruffian behind him. The only creature to take any notice is a barking dog: the potential purchasers are ignoring real-life drama to study the imaginary displays of human folly.

This illustration by Gillray of a shop selling his own prints belongs to a voyeuristic genre that was popular at the time; several other examples survive showing a doubly fantasised world of imaginary spectators and artistic creations. The caricatures in the shop windows can often be identified—in one example, the botanist Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, is portrayed foolishly chasing after evanescent butterflies. They challenge our own position as external viewers by implicitly posing a philosophical question: what does it mean to represent? Like the characters in the prints, the passers-by gazing through the window are themselves caricatured. Immediately distinguishable by the shapes of their hats, they are also contrasted socially, ranging from the smartly dressed but pompous gentleman on the left down to the small boy with a syphilitic nose and a pair of skates. But where does that leave us as we contemplate this multiple scene? Do we too belong to an array of satirical types? Are we also prey to the follies and petty vices of humanity that Gillray exposed so ruthlessly?