In November 1974, Yasser Arafat delivered a speech at the UN in New York. The PLO leader, viewed by the US government as a terrorist, attacked “Zionist racists and colonialists” and honoured the “popular armed struggle” to free Palestine. But he ended with a (qualified) peace offering: “Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom-fighter’s gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.” Those resonant lines came from the pen of nearby Columbia University’s Edward Said. Some of his older colleagues might have been surprised that Said, an expert on Joseph Conrad, was moonlighting for Arafat. When he was first hired, it was rumoured he was an Alexandrian Jew.

Such paradoxes followed Said around. His close friends nicknamed him both “Abu Wadie,” echoing a militant’s nom du guerre, and “Eduardo,” a suave Renaissance man. At his most optimistic, Said saw himself as he described his hero Jonathan Swift, as both a “man of letters and a man of action.” Yet throughout his work runs a darker fear that his political and literary interests, which he fused in the hugely influential Orientalism (1978), were ultimately incompatible. That book argued that western writing about the east is inevitably belittling because of the unequal power relations between the describers and those being described. It is one of those rare books that founded a new discipline—postcolonial studies—and ensured the dusty term “Orientalism” became charged with negative connotations. You can still see it being used on social media to discredit western commentators on Islam.

Towards the end of his life, he elevated “intransigence, difficulty and unresolved contradiction” into a credo—these words serve as the epigraph to Timothy Brennan’s new biography, Places of Mind. But Said’s intransigence was not always admirable, and his contradictions often mere confusion. He veered from trashing European scholars of the orient to venerating their achievements; from defending Islam against western calumnies to condemning fundamentalists who had learned his lessons all too well. Finally, he returned to western high culture after making his name labelling it as complicit with colonialism. He went, as it were, from Eduardo to Abu Wadie and back again.

Edward William Said was born in Jerusalem in 1935 to a Palestinian family, delivered by a Jewish midwife. His family mainly lived in Cairo, but Jerusalem was their spiritual home: it was where Said was baptised as an Anglican—a small minority among Arab Christians. Named for the Prince of Wales who would shortly become Edward VIII, he grew up speaking English and French. (He knew local dialects but only studied literary Arabic as an adult.) Classical music was an early passion. As a boy, he attended the Khedival Opera House, which had premiered Verdi’s Aida in 1871. He learned piano on a baby grand imported from Leipzig, and took lessons with Ignace Tiegerman, a Polish-Jewish émigré. (He hated Arabic music and compared singer Umm Kulthum’s voice to wailing.) At Victoria College, the Eton of Egypt, he was a classmate of Omar Sharif. All this privilege was paid for by his father Wadie’s stationery business, which supplied the occupying British army with the paper to write imperial reports.

Wadie had moved to America during the First World War and Edward inherited the US citizenship he had acquired. Aged 15, he was sent to boarding school in Massachusetts. While Said admitted that “to call me a refugee is probably overstating it a bit,” his family had lost its Jerusalem home after Israel’s founding in 1948. There was further trouble. In 1952, anti-British Egyptian nationalists burned down hundreds of businesses, including his family’s. Oddly, writes Brennan, Said would later blame this on the Muslim Brotherhood rather than the secularists responsible.

Said tried to bury his past. He went to Princeton and Harvard before joining Columbia, where he worked with Lionel Trilling and RP Blackmur. In 1962 he married Maire Jaanus, who was, according to one of Said’s colleagues, a “ravishing” Estonian and “a cross between Garbo and Bergman.” Still, he always felt, in his own words, “not quite right” and he faced patrician racism from some of his colleagues. His repressed origins would burst out unexpectedly: on the way to a concert in New York, he crossed the road rather than face an Orthodox Jew; a roommate once heard him speaking Arabic in his sleep.

Two events shook Said up. The first was the 1967 Arab-Israeli war; the second was his father’s death four years later. He was haunted by his lost homeland, and tried to regain the Arab self crushed by his western education. By now the relationship with Maire—who called him a “knotted fusion”—had fallen apart. In 1970, he married a Lebanese Quaker called Mariam, and had become a point of contact between the PLO and the US government. He was rather embarrassed by the rougher aspects of the liberation movement: the violence, of course, but also Arafat’s scruffy appearance. Always a dapper dresser himself, he once suggested the chairman drop the keffiyeh and military garb.

References to Islam and the Arab world began to appear in his literary criticism, though they were hardly complimentary. In 1975’s Beginnings, he argued that Arab novelists were parasitic on European models: “the desire to create an alternative world, to modify or augment the real world through the act of writing,” he wrote, “is inimical to the Islamic world view.” (He often wrote as though only the Arab world was Islamic.) Sounding like a (very) old-school orientalist, he claimed the Prophet Mohammed had “completed a world view; thus the word heresy in Arabic is synonymous with the verb ‘to innovate’ or ‘to begin.’” His private writings were similarly scathing. Why have Arabs, he despaired in a letter, “no sense of efficiency, of progress… of science or cultural vivacity?” Not since the 14th-century thinker Ibn Khaldun had they produced a “theory of mind,” and even he had borrowed from Aristotle.

It is impossible to understand the conflicted, uneven and sometimes misleading nature of Orientalism without first recognising Said’s secret fear that critical portrayals of Arabs by Europeans might have a point. Partly this was ignorance. He seemed uninterested in those eastern thinkers—not all Arabs or Muslims—who had influenced the west’s orientalists, argued with them or absorbed their insights. (See Noel Malcolm’s Useful Enemies on changing European attitudes to the Ottoman Empire—a vast entity ignored by Said—and Leor Halevi’s Modern Things on Trial, an account of how 19th-century Egyptians responded creatively to new technology.) Famously, there is very little Arabic actually quoted in Orientalism.

That fear sublimated into anger directed at the imperial writings that had formed his own mind. Orientalism argues that all knowledge of the east “is somehow tinged and impressed with, violated by, the gross political fact” of colonialism. (Note the rhetorical elevation.) Orientalism, he says, began with Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, or maybe with Dante, or even Aeschylus’ The Persians. This confusion can be traced to competing theoretical influences. Critics like Trilling emphasised empirical facts and political context; Michel Foucault, on whom Said lectured, claimed texts did not speak to a “real world,” but only to each other in a self-referential loop shaped by power relations. If reality doesn’t matter, only historical texts, then orientalism can go as far back as Homer.

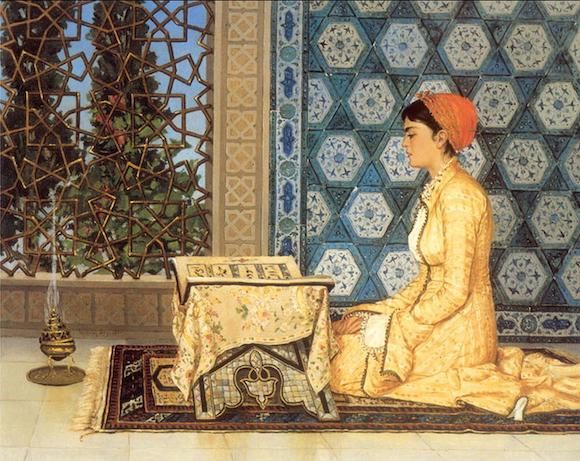

But turning his argument into a totalising theory inevitably resulted in drastic simplifications. Arabists Robert Irwin and Daniel Martin Varisco have laid out the charges: ignoring German and Russian orientalists because those countries didn’t have Middle Eastern empires; conflating philological studies like Edward Lane’s Arabic lexicon and literary works by Goethe and Flaubert; and reducing the art of western orientalists to lascivious stereotypes, while missing its influence on Muslim painters like Osman Hamdi Bey. In jittery prose, the book has some curious asides—one scholar is said to have “ransacked” the oriental archives, when all he did was consult them.

Remarkably, at the book’s close Said retracts his own thesis: orientalist “scholars and critics,” he writes, “are perfectly capable of freeing themselves from the old ideological straitjacket.” So, you might ask, what’s your point? In The World, the Text and the Critic (1983), he lavishes praise on the French scholar Louis Massignon for his biography of Sufi saint al-Hallaj. Massignon, a translator at the Sykes-Picot conference, could have been the archetypal orientalist-imperialist agent. But—the Said contradiction again—the Frenchman’s scholarship was too good.

“Said’s overstatements were designed to unleash a purifying indignation in his readers,” writes Brennan in exculpation; “he felt he had to be strong and definite for political reasons.” Singular explanations could be relied on to make an impression, no matter how impressionistic. Orientalism was a hit, and negative scholarly reviews could not derail the juggernaut. Many readers from ex-colonies responded to the explicitly personal nature of the argument: “My study of orientalism has been an attempt to inventory the traces upon me, the Oriental subject, of the culture whose domination has been so powerful.” It released something in them, as it had done in Said.

That was certainly true of me. At university, struggling with the very English study of English literature, I identified with Said’s outrage. It helped that he was a charismatic New York intellectual who spoke with righteous anger about Palestine. One of his assistants, Deborah Poole, says he taught her “the place of rage in scholarship.” Before debating his academic nemesis and Ottoman expert, Bernard Lewis, he whispered to a friend in Arabic: “I am going to fuck his mother.”

Lewis was somewhat of an obsession. In Orientalism, he quotes his essay on thawra, or revolution, which traces the original meaning of the Arabic word to the motion of a camel standing up. This lexicographical detail provokes an extraordinary outburst, Said claiming that Lewis “is patently trying to bring down revolution… to nothing more noble (or beautiful) than a camel about to raise itself from the ground.” Funny, I’ve always thought it rather a majestic sight. He goes on to read a crude insult into Lewis’s translations “stirred, excited and rising up”—“since Arabs are really not equipped for serious action, their sexual excitement is no more noble than a camel’s rising up… instead of copulation the Arab can only achieve foreplay, masturbation, coitus interruptus.” Clearly, Said had a rather old-fashioned view of what constituted “serious action” in the bedroom.

In an elegant book-length response to Said, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (1982), Lewis showed that the internally sophisticated Islamic world had, until the advent of western colonialism, considerably less interest in European history and culture than the other way round. Though since Said sometimes equated intellectual curiosity with the urge to dominate, perhaps he thought this no bad thing.

His rage at Lewis was as much for his Zionism as his orientalism. In the 1980s, as the PLO remained stuck in exile, Said became more intemperate. During the first intifada, he responded to reports that Palestinians accused of spying for Israel had been summarily shot: “Why is it somehow OK for white people… to punish collaborators during periods of military occupation, and not OK for Palestinians to do the same?” The irony was that, in 1989, Said began receiving threats after a rumour spread that he was a US spy. (He already had special protection at Columbia after his office was ransacked by militant Zionists.) Partly this was due to his efforts as a go-between. In 1988, he had met Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state George Shultz to discuss the PLO’s proposed recognition of Israel. Shultz had read Beginnings and happily chatted with the man widely dubbed the “Professor of Terror.”

Brennan wrote a thesis on Salman Rushdie under Said’s supervision, so it is curious there is nothing here about The Satanic Verses controversy. Interviewed shortly before his death in 2003, Said said he read the novel in proof after visiting Rushdie at his Islington home. (It was 4th July and they set off fireworks in the garden.) The novelist foresaw “Muslims will be very angry,” and Said recognised the “dynamite” within its distorted portrait of the Prophet Mohammed. As well he might. In Orientalism, Said lambasts William Muir for his 1861 Life of Mahomet, which portrays Islam’s founder as one of “the most stubborn enemies of civilisation, liberty, and the truth”—a strikingly similar depiction to Rushdie’s “Mahound.” The incendiary phrase “satanic verses”—though not the actual incident of prophetic doubt, which occurs in Islamic sources—first appears in Muir.

In a 1995 afterword to Orientalism, Said dismissed Muslims who had seen his book as freeing Islam from the clutches of western scholars; but he had certainly left himself open to this interpretation. Later, he would airily declare religion to be “the most dangerous of threats to the humanistic enterprise”—thus consigning Muslim scholars of Islam, say, to the periphery.

When Said returned to the European canon, he brought plenty of heavy political baggage. In 1993’s Culture and Imperialism, he famously spots allusions to slavery in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Said was right in one sense: Austen was surely aware of the heated debate on the cruel trade going on in England at the time, and references to slavery do creep into her work. Recent efforts by the Jane Austen Museum to explore the issue are perfectly legitimate. But in his rush to apportion guilt, Said once more trips over himself.

When the heroine Fanny Price asks her uncle Sir Thomas Bertram, who owns Antigua plantations, about slavery she reports there “was such a dead silence!” From this Said extrapolates the novel’s “affiliations with a sordid history”—the slippery term “affiliations” does a lot of work here—arguing that Mansfield Park “opens up a broad expanse of domestic imperialist culture without which Britain’s subsequent acquisition of territory would not have been possible.” No Austen, no British Empire.

Said, however, burdens the author with both too much responsibility—the empire would likely have rumbled on without Austen to grease its ideological wheels—and too little credit. Fanny boldly raises the issue with her uncle because she sees parallels between her own situation as a poor relation and that of his slaves. Sir Thomas’s “dead silence,” as well as that of his complacent family, shows up their moral blankness, not the author’s. Austen’s contemporary readers might also have recalled that it was Lord Justice Mansfield who declared British slavery illegal in 1772. (Said’s argument is further weakened by the mysterious listing of Pride and Prejudice’s Lydia Bennet as a character from Mansfield Park.) Yet, once again, he diagnosed his own worst tendencies. Before publication, he fretted to a friend: “I don’t want you to think of me as treating literature only as a vehicle for my convictions.”

The last decade of Said’s life was painful. He was diagnosed with leukaemia in 1991 and two years later broke with Arafat over what he saw as the Quisling Oslo Accords. His daughter Najla thought he suffered from depression and Brennan identifies a “profound insecurity about his own identity,” that caused “a violent oscillation between boastfulness and self-doubt.” In 1995, he resumed an affair with the Lebanese writer Dominique Eddé—about whom Brennan, perhaps mindful of Said’s widow, is aggressively dismissive.

Comfort came from his early love—classical music. With Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim, he set up an orchestra for Israelis and Arabs to play together. The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra—named for Goethe’s oriental fantasy—is Said’s greatest legacy. Finally, he released culture from the prison of politics and grand theories and once more allowed himself to experience its transcendent pleasures. Listening to his beloved Beethoven, Said knew that it did not matter which notes were played by Jews and which by Arabs.