“In parliamentary work, ‘standstill’ may appear agonising, yet for voters it doesn’t hold any horror in times of crisis,” the late German journalist Roger Willemsen wrote after witnessing a Bundestag debate in March 2013, six months before the last general election in Germany. “The [Social Democratic] opposition may have found the government’s blockades a hard nut to crack—citizens however desire above all to maintain the status quo. For them, the inertia… isn’t an argument for voting anyone out. ‘Standstill’ simply has too good a reputation these days.”

The subsequent September 2013 election gave Angela Merkel her third term as Chancellor. As it stands, Willemsen’s observation could just as easily apply this summer. Then as now, Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) alliance was the largest party in a coalition government. Some ministers have changed and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), then the main opposition party, is today part of the government—not that it makes much of a difference. Then, the crisis Germans worried about was of the euro and Greek debt; today, it is of refugees and a shifting world order. Then, the man prodding Germans with his visions for the future with signs of increasing desperation, was Peer Steinbrück; today, it is Martin Schulz. We will be forgiven for mixing them up in 10 years’ time. In Germany, 24th September 2017 could just as well be called Groundhog Election Day.

In much of the west, voters have been keen to break things—or at the very least break with the past. The UK has voted to leave the European Union and is dallying with the idea of a radical socialist prime minister; France has given its established parties a good kicking; and the US, of course, has decided to administer that kicking to not only to its own establishment but to the world as a whole, by electing Donald Trump. The Polish, Hungarian and Turkish regimes are moving to undermine liberal democracy. Countries and communities are ever-more polarised.

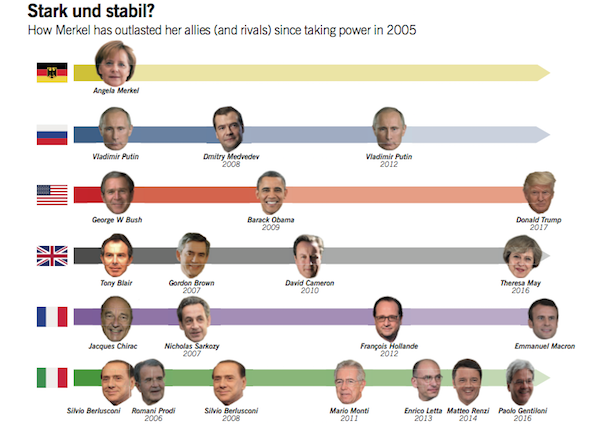

But while a common refrain among pollsters, pundits and random bystanders after the US election was “we don’t know anything anymore”—the rhetorical equivalent of throwing one’s hands in the air—there is something they all predict with increasing certainty: on 25th September, Merkel will still be chancellor. At the end of July, Merkel’s CDU/CSU union was polling at 40 per cent, leaving her main rival the SPD out of view at a distant 23 per cent. Merkel herself had a 69 per cent approval rating. Granted, campaigning had not yet officially begun—and Merkel may recall that Theresa May had an even larger lead than that before the UK election campaign began earlier this year. But Germany isn’t a country for surprises. The truism that “elections have consequences” is simply less true in Germany.

Many a troubled citizen of this troubled world have come to invest an awful lot of hope in Merkel—regarding her as the redoubtable, backstop defender of the world’s liberal order, and “the last adult in the room.” Predictions of her re-election will, no doubt, be music to their ears, but if they imagine Angela the Fourth is going to push the planet in a progressive direction they are deluded. For despite her image, gained during the refugee crisis and in the midst of global confusion, as a great humanitarian as well as a great stateswoman, Merkel is in truth a smaller and more managerial figure—reactive, and in some senses at least, essentially reactionary. The upcoming elections could leave her at the helm of a more conservative government still, with repercussions for Europe and the world. Indeed, even if it resolves itself to vote for a “standstill,” Germany may be on the brink of a period of profound change.

It is a cliché that Merkel governs by public opinion—and like all the best clichés, it is true. The chancellery’s press office commissions several detailed polls every week, providing Merkel with insight into what the electorate currently cares about, what can fall by the wayside and which issues are too toxic to touch. It is hard to attack somebody who is so tuned into her electorate’s whims, who puts virtually no demands to the German people, a woman who has weaponised her blandness.

“The SPD is left trying to convince risk-averse Germans that change is necessary without rattling their overall sense of comfort”

Schulz’s SPD, meanwhile, is trying to convince Germans that they don’t live well enough—or that, at the very least, the good times can’t last forever. He has made social justice his core theme during this election. As with other ageing leftists (think Jeremy Corbyn or Bernie Sanders), his focus is on class rather than ethnicity or gender, and social justice within Germany, rather than the planet or the continent—an irony, since Schulz was President of the European Parliament until the beginning of the year, and remains a devotee of the EU’s supranational institutions.

He has identified undoubted problems: a dearth of public investment in infrastructure, a tax system that doesn’t protect the neediest, increasingly insecure employment terms and expensive urban rents. His problem, however, is that most Germans simply don’t feel the system as a whole is inherently unfair—at least not in the way he portrays it. Only 20 per cent of Germans rate social injustice as an important problem, compared to 44 per cent who believe that refugee policy needs to be addressed. The language of class warfare may enjoy a new purchase in today’s vastly-unequal United States, and in Britain, where neoliberal policies have also left a deep mark. But many of the most aggrieved Germans are those who bear grudges against Merkel for what they regard as the prioritisation of refugees in the welfare system. They might be more tempted to vote for the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) than the SPD. By trying to appeal to as broad a base as possible, Schulz has purposely omitted groups who might truly feel disadvantaged and be sympathetic to the left, like young women and minorities. Indeed, the SPD conspicuously remains a party of older white men, which makes it hard to build a Corbyn-style surge among the young. In effect, Schulz is trying to convince risk-averse Germans that change is necessary without rattling their overall sense of comfort and security. The result is an electoral programme that is so sensible and uncontentious that Merkel can safely pilfer all the best bits.

Hijacking other parties’ popular ideas is, of course, another Merkel trademark. Over the past years she appropriated many of the Green Party’s core proposals on environmentalism (think of her famous swerve against nuclear power), making the Greens—which were a junior partner in Gerhard Schröder’s government in the early 2000s—appear obsolete. By brokering a grubby deal between the EU and Turkey and encouraging the Bundestag to tighten asylum laws, she also recently curbed the influx of refugees into Germany—quietly calling time on the move which much of the world regards as her great achievement. It deprived the AfD of its most salient argument without, of course, ever airing or even acknowledging the far-right’s demands. It worked. On 27th July, the AfD polled at 9 per cent in infraTest’s weekly survey, far from the 16 per cent at its height in September 2016, and media coverage of the party has withered. The Left, the Greens and the liberal FDP all polled at 8 per cent. In sum, as the election campaign gets ready to begin, Merkel once again looks unassailable.

Germans who dream of a radically different domestic agenda will be frustrated by this. Liberals outside Germany, however, may not spot any problem—indeed, they are more likely to look towards Merkel’s prospective re-election as an much-needed shot in the arm for a global liberal order in disarray. After all, this is a woman who has steered the EU through several crises, and is working to keep international agreements and the spirit of multilateralism afloat even as Donald Trump tries to sink them.

Such a sanguine reading of what Merkel means for the world is, however, completely wrong. Why? First of all, Germany is in no position to defend the west—neither ideologically nor militarily. Occupied West Germany may have joined Nato after the Second World War, but armed alliances have never quite fitted with Germany’s self-image. Moreover, German international leadership is simply something the country itself is uncomfortable with, to say nothing of how its European neighbours feel about it. And given the German public’s distaste for military embroilment, Merkel is most unlikely to pursue a more active use of an army, which has anyway been struggling with recruitment since the abolition of universal conscription in 2011. In a recent op-ed in Die Zeit, the Green former deputy chancellor and foreign minister Joschka Fischer called Germany’s army, the Bundeswehr, in its current state “an overpriced spare parts inventory.” He added that “no country… is as little prepared as ours” for dealing with the power vacuum that Trump’s America is creating.

“Politics, not principle, underlays her signature move on the refugees, and politics has undone it since”

Moreover, the upcoming elections are likely to render a distinctly more conservative government than the current one. Merkel’s party has long been locked in to a permanent pact with its distinctly right-wing sister, the CSU, standing aside to give it a clear run in its conservative Bavarian home. For the past four years, the CDU/CSU have led a “grand coalition” alongside the Social Democrats, necessitating compromise and weakening the hand of the internal CSU wing. Looking ahead, even if the CDU and CSU somewhat undershoot their current polling, they are unlikely to need another grand coalition. This will increase the CSU’s influence and pull the new government further to the right. One could think of the CSU as the German equivalent to the Texas Republican party. Granted, conservatism works differently in Germany than in the US; the CSU isn’t trying to abolish business regulations or abortion rights. But it is the strongest proponent of the traditional West German ideal of the nuclear family with a single (male) breadwinner. It was the CSU which in 2012 managed to introduce a childcare subsidy for stay-at-home parents commonly derided as a “cooker premium,” which bribes women to avoid returning to work.

That was just one distinctly Bavarian move that the CSU has pushed through on a federal level. Its current pet project is an official upper limit on asylum seekers, which Merkel has so far resisted. It operates by an unstated rule that it can never allow there to be a legitimate party to its right, so it responded to the rise of the AfD by matching its anti-Muslim and anti-refugee rhetoric. Horst Seehofer, the CSU’s head, was for months the harshest and loudest critic of Merkel’s refugee policy, before the two made a show of publicly reconciling this spring. The Bavarian state parliament has just passed a law extending preventive detention of potential criminals from two weeks to three months, and indefinitely when a judge gives the green light. There are echoes here of Tony Blair’s failed attempts to increase detention of terror suspects in the UK to 90 days. This is not a liberal agenda.

Civil servants at the Interior Ministry already predict a CSU, instead of a CDU, interior minister. A stricter asylum policy, new immigration controls and increased surveillance could well be their top priorities. Much more generally, with a more conservative government, Germany will likely regard the world outside less as an opportunity, and more as a threat.

Yet the more fundamental reason why it would be a mistake to regard Merkel as the great saviour of the liberal order is that she herself is no paragon of high principle, or at least not of progressive principle. International observers were surprised when they saw her vote against same-sex marriage in a hastily arranged division in the final Bundestag session in June. They seem to have forgotten that she is a Protestant minister’s daughter, the head of a party with “Christian” in its name. It is perfectly possible that she voted her conscience, which is what she had urged MPs to do. But conscience or not, on the gay marriage issue, the shrewd tactician was undoubtedly at work: by hastily allowing the Bundestag vote, she removed a potentially thorny election issue, something that had majority support among the population but not in her own party.

Similarly, opening Germany’s borders to take in hundreds of thousands of refugees was in truth more another act of calculation than a humanitarian impulse. As Die Welt journalist Robin Alexander shows in his book Die Getriebenen (The Driven Ones),“The woman who will enter the annals of German history as the refugee chancellor has during her chancellorship avoided few people as long and as consistently as refugees,” he writes. During most of Merkel’s reign, asylum applications were at historic lows. Even as the crisis became ever-harder to ignore during 2014, Merkel did not publicly address the issue, and she didn’t visit a refugee centre until August 2015, when political pressure forced her hand. Her mind changed on the policy only after there was a massive wave of sympathy for refugees among the German public. It was politics rather than principle that lay behind her signature initiative, and politics which has undone it since.

Merkel is certainly an experienced stateswoman, and—to most Germans—safe pair of hands in confusing times. But she is also a ponderous ditherer who, on the whole, follows rather than leads. Those searching for a lodestar for the liberal world must look elsewhere.

The many Merkels:

2005-2009: After a narrow victory over Gerhard Schröder, Merkel was forced to govern in a grand coalition with the SPD. Being Germany’s first female chancellor was the only thing remarkable about her uneventful early years, yet once the financial crisis hit she launched bold economic stimulus packages and help for Germany’s car industry.

2009-2013: The CDU/CSU vote rose dramatically, allowing Merkel to ditch the SPD and form a coalition with the business-friendly FDP (though an uneasy start stymied plans for a sweeping tax reform). This Merkel term saw the abolition of universal conscription, the sudden decision to phase out nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster in early 2011 and the revelation that NSA surveillance covered even Merkel’s mobile phone.

2013-2017: Another grand coalition with the SPD led to a parliament in which 80 per cent of all members were part of the government. During her third term, foreign policy became increasingly important and Merkel’s image changed dramatically, from the iron lady who had brought austerity to Europe to the great humanitarian of the refugee crisis and the stateswoman drily handling men like Erdogan and Trump.

Additional photo credits: ADREAS RENTZ/GETTY IMAGES, SEAN GALLUP/GETTY IMAGES, ROBERT MICHAEL/AFP/GETTY IMAGES