“The politics of land use, long policed by the planning system, has degenerated into warfare, and at its core lies housing”

Where should the houses go? In a country as small as Britain there is too little space to grow food, to walk, admire the view, build factories, offices, towns and cities. There is too little space for houses, especially houses.

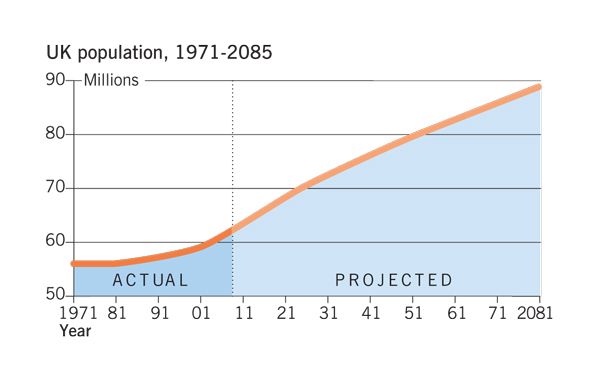

The population of the United Kingdom today is 63m, up from 42m a century ago and 4m more than in 2001. The main driver of this growth, immigration, means that the total is expected to reach 77m by 2050. While the population increase is far lower than in the 19th century and tends to ease during recession, the long-term rise seems certain to continue.

These people must occupy land. The UK as a whole is one of the most densely populated countries in Europe—taken by itself, England’s population density is the second highest in the EU, at nearly 1,000 people per acre. Yet it is housed as well as anywhere in Europe while retaining, virtually untrammelled, up to 93 per cent of its surface area as “rural,” according to extensive research conducted as part of the “UK National Ecosystem Assessment” in 2011. This phenomenon has been achieved through town and country planning acts in place since the Second World War, delineating a boundary between urban and rural development.

This boundary is now all but collapsing. Following reforms to planning regulations last year, there are currently calls to build up to 80,000 new houses on green belt land. This is despite de-industrialisation leaving more derelict land, probably, than ever before in British history. The nature of the housing market, heavily skewed towards the southeast of England, is directing builders towards the countryside, where it conflicts with rural communities and conservationists. The politics of land use, long policed by the planning system, has degenerated into warfare, and at its core lies housing.

Everyone wants a better house, preferably one with a garden in the country. A poll conducted for Prospect by YouGov took as axiomatic that this has led to a crisis in housing. Yet respondents showed little interest in relaxing rural planning for more building in the countryside. The overwhelming priority (along with reducing immigration) was for schemes of shared equity and fiscal incentives to use houses more efficiently. Other polls show similar results. The “English countryside” ranks with the royal family, Shakespeare and the NHS as evoking maximum pride among Britons. It is regarded as very precious.

All political parties regard housing supply as being both the cause and the result of economic regeneration. In his last budget George Osborne, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, sought to stimulate growth by giving a “kick-start” to house building, despite three years of such kicks having had no effect. House prices since 2008 had fallen by 11 per cent. Now Osborne pledged an astonishing £130bn to back interest-free “help to buy” loans, covering 20 per cent of a house’s price. There was an additional guarantee of up to 95 per cent for some mortgages. For good measure Osborne also proposed that homeowners be allowed to build into their back gardens without planning permission.

The Treasury Select Committee and other experts were contemptuous of these proposals. Osborne seemed to be replicating America’s Fannie Mae fiasco, during which an organisation that was partly government controlled found itself caught up in the great housing bubble that led to the credit crunch. Such huge sums from government would merely force up prices and not help buyers at all, while taxpayers would face large losses on the guarantees if prices fell.

Emotion is rarely a sound guide to policy, and no policy comes with more emotional baggage than housing. Few Britons live without a roof over their head, yet a better house has acquired the ideological status of a “human right.” Politicians talk of the right to buy, the right to an affordable home, the right to family life, the right to community. For as long as I can recall, housing has been “in crisis,” irrespective of whether prices are rising or falling.

At the heart of policy is the concept of housing need. Each year statisticians announce predicted rates of “household formation” and thus the number of “new houses needed to meet it.” This concept of a fixed national accommodation requirement is a last outpost of Leninist social planning. The figure purports to chart marriage, divorce, immigration and children leaving home. It mysteriously always hovers round 250,000 “new households” a year.

This figure bears no relation to shifts in social benefits, parental income or student finance. It takes no account of internal migration, social habits among different migrant groups or the rise in second homes (around 250,000 by 2009). Britons make widely varying demands on space, according to where they live and work, their means and social inclination. We all want our children to move on, except that when they do we expect government to supply them with an “affordable” home nearby. Such desires, unrelated to price, are a miasma. Cramming them into a crude statistic of “need” is no guide to policy.

Yet need has been gold dust to politicians and developer lobbyists alike. Housing policy first entered “the politics of the centre ground” in the 1960s. Tax relief for mortgage interest was introduced by Roy Jenkins in 1969 and grew to become the biggest ever middle-class subsidy. Its fiercest defender was Margaret Thatcher, who equated home-ownership with democracy, and was spending £7bn a year on relief by the time she left office. Economists accused her of inflating prices and diverting the nation’s savings from productive investment. Thatcher retorted (in her memoirs) that “most people are not born entrepreneurs.”

The subsidy was curbed by Ken Clarke in the 1990s and abandoned by Gordon Brown in 2000. Shortly afterwards, around 70 per cent of British households were owner-occupiers, compared with 43 per cent of Germans and 56 per cent of Dutch and French. The median age of first-time buyers was just 28. Even today, only 17 per cent of Britons rent privately, usually regarded as an aid to labour mobility, against 48 per cent of Germans.

Nor has policy been kind only to homeowners. Britain pioneered social housing, from Octavia Hill, founder of the National Trust, and the early London County Council, through interwar slum clearance and on to post-war new towns. Such housing soon acquired an aura of entitlement. Housing points were awarded not just for need, but for place of birth, parentage, longevity, proximity and family size. Immigrants were accommodated with a generosity that became legendary across the distant world. Keys to east London flats were said to be traded in the markets of west Africa.

As housing became ever more politicised so it became nationalised. The central government moved vast numbers out of cities into the countryside. In the 70s, I witnessed the “decanting” of Moss Side, as thousands were sent in coaches to Skelmersdale and elsewhere, like dazed wartime refugees. In the woods round Meriden outside Birmingham, 60,000 people were dumped in what seemed like giant barracks. City centres depopulated. Cleared acres lay empty. There were, of course, never “enough” houses and it was always the government’s fault.

By the time the present government came to office, public housing had all but ceased and private housing was in the grip of recession. Prices that had soared in the boom years crashed, falling by a third in some parts of the country as demand dried up. Only in London’s economic area did they remain reasonably stable. The familiar signs of stagnation showed themselves. Some 400,000 plots with planning permission lay undeveloped. More than 660,000 homes were registered as empty in 2011, nearly half of them for more than six months. Roughly 1.5m sites designated for housing under urban renewal were not used. Developers had no interest in dipping into their land banks, though they did have interest in increasing those banks while prices were low.

Meanwhile tracker mortgages were cheaper than ever. At 3 to 5 per cent, rates were a quarter of what they were when I bought my first house. What is making it so difficult for first-time buyers now is the size of deposits. Banks used to waive these given the expectation of constantly rising house values. That stopped when the bubble burst. House buying is now for those with access to savings, or with rich parents. Others must rent. But this is not a crisis, just a fact of life. Osborne’s desire to stir the market to life with deposit guarantees makes some sense here, provided it is strictly short term.

What makes no sense is Osborne’s other tenet, that economic revival is impeded by a shortage of land for development. Newly built houses seldom add more than 1 per cent of Britain’s housing stock, and rarely more than 10 per cent of annual transactions. Even then, most new houses are still built in existing towns. Housing demand reflects, as it always has, the general state of the economy and of housing finance. Even the most ardent enthusiast for house building, the economist Kate Barker, admits that “changes in the supply of land have very little effect on short term prices.”

The recent, reckless housing boom was a demand phenomenon, fuelled by wild fluctuations in the availability of finance. Tracking by the Economist showed prices rising fast in America, South Africa and Australia, where there were few land constraints, and slow in Japan and Germany, where there were many. Britain and Spain were roughly in between. Supply of land was immaterial. Finance was the determinant. Yet ministers still maintain the opposite, impelled by the emotion attached to housing need and by developer lobbyists whose profitability is usually highest on rural estates.

The overwhelming pressure of population in England is towards the southeast. Half a century of regional policy has largely failed to relocate economic growth to the north. There are many explanations for this, but experience abroad suggests that fiscal incentives have been weak and urban renewal inadequate. Growth has not been directed towards reusing the human and physical resources of the north, while the redirection of the economy into financial services has fuelled the magnetism of London. The gap between London and the rest of Britain continues to rise. Small terraced cottages go for £1m in Notting Hill, while similar (albeit rundown) properties in Stoke-on-Trent were priced at just £1 in a recent sale.

Housing policy is a derivative of such overall economic planning, but it too has been poorly directed. Since the war it has favoured dispersal from existing cities into the surrounding country. The central area populations of Manchester, Sheffield, Liverpool and Birmingham, as well as London Docklands, dropped dramatically in the 1970s. Cities died, and with them went their social, economic and physical infrastructure. Nikolaus Pevsner remarked that the dispersal of Merseyside over south Lancashire since the war had yielded the largest urbanised sprawl in Europe. “Countryside colonisation” imposed a vast, if unquantifiable, resource cost on Britain.

The last government’s Urban Task Force, under Richard Rogers in 1999, argued forcefully that low density “suburban” living was no longer realistic. It was costly and environmentally destructive. At fewer than eight houses to the acre, journeys to work, shop or play tended to need a car. The task force recommended 16 or more houses to the acre as the minimum “sustainable” for village-scale communities. It was also commonsensical to concentrate development where there were already utilities and services.

Under the last Labour government, a real attempt was made to re-engineer Britain’s economic development in this direction. Planning policy directed 70 per cent of new building into existing urban areas. The resulting economic regeneration of central Liverpool, Birmingham and Newcastle was noticeable. New urban developments such as Kirkstall Forge in the once derelict Aire Valley outside Leeds pointed the way.

With the coming to power of the coalition in 2010, intense commercial pressure was put on ministers to end this policy of “brown-field first.” This led initially to its removal from new draft planning guidelines. In its place was a drastic change in emphasis towards relaxing controls on building in the countryside. Whitehall regulations were openly drafted by the Home Builders Federation and other property groups. Business was now to take priority over conservation.

New plans had to be drawn up supplying rural land for development virtually everywhere. Labour’s targets were taken as a base line and a requirement imposed to meet “five years of housing need,” with an additional buffer of 5 per cent. This was to be applied even in protected parks and green belts.

As before, the word “need” was left obscure. It was described as “need for all types of housing,” or a need to cater “for housing demand and the scale of housing supply necessary to meet that demand.” Given that almost all rural land is “needed” to the property market, this definition was intellectually chaotic. Where councils failed to meet their “deliverable” targets of new land supply, planning permission for any building could take place wherever it was “sustainable.” This phrase embraced some concept of energy efficiency, but in practice it was interpreted as “commercially viable.” Thus in Salford, Eric Pickles, the Communities Minister, allowed a development of 350 houses on green land outside the city, while ignoring land allocated by the council for 19,000 homes inside it.

Some of what was proposed made sense. Many planning regulations—like those on building materials, health and safety—were archaic, inefficient and unnecessary. Planning was too dilatory. A junior minister, Nick Boles, proposed to ease the use-classes order, enabling change of use between commercial and residential. He also sought changes in “right to light” rules and controls on rear extensions for a three-year period. These were controversial, though not all were unreasonable. He did nothing to end VAT on all conversions to existing buildings, while it remained waived on new builds.

The new planning framework was toned down in its final 2012 form. But its axiom, that land supply was critical for economic growth, remained. Planning inspectors went to work on rural communities and the impact was instantaneous. Despite housing “need” being an overwhelmingly urban phenomenon, housing strategy was a matter of new building in the countryside. The result was open warfare.

The Cotswold town of Stow-on-the-Wold was told initially to increase its population by a third, or 1,000. Similar orders went out to Tetbury, Tewkesbury, Winchester, Petersfield, Ashford and many others, in each case sparking a furious local response. Nor was this assault simply on the southeast. Land supply targets were issued to Stratford-on-Avon, Sandbach and Yarm and green belts around Nottingham, Durham, Gateshead and Newcastle were infringed upon. The Campaign to Protect Rural England registered plans for 80,000 houses in green belts.

The consequence of such breakneck deregulation is no mystery. Its domestic impact can be seen in the sprawl around Bristol, across the east Midlands or in south Essex. On a grander scale it is manifest in the unplanned acres of rural Ireland, or in southern Portugal, Sicily and Greece, much of it speculative building distorted by EU subsidies. A new European landscape is being born, of random buildings, often unfinished, scattered across hills and valleys. Similar development in New Jersey and southern California yields miles of “plotlands,” where suburban living is a slave to the motor car, and leisure a slave to hours of driving to find somewhere to wander free.

Economic sense would concentrate new development on the de-industrialised areas of Britain, on the millions of acres of already settled land where infrastructure is in place and higher densities are easy to achieve. There is no “need” to colonise rural Britain for new building. There is merely a demand from people wanting houses in the countryside, usually the same people who tell pollsters they want the countryside preserved. Curbing that demand through the planning system is painful and involves rural house prices responding to demand. But development should be determined by how most people want their country to look. They expect the environment to be policed.

Just as there are parts of the countryside where new development is visually and environmentally harmful, so there are clearly parts where development is unobjectionable, where fields lack scenic or recreational value and where existing infrastructure can cope. Their need is only for sensitive planning.

Such a template exists already in the way we plan towns. Here are rules on sight lines, road widths, building standards and architectural conservation. There are no wind farms on Hampstead Heath or high-rises in Belgrave Square. We no longer demolish Georgian terraces or Victorian mills, much to the advantage of Bath and Hebden Bridge. A collective view has been reached on the future of Britain’s towns, agreed by land and property owners even where it means diminished profit.

The same should apply to the countryside. Already some 15 per cent of England and Wales is national park, green belt or within areas of outstanding natural beauty. A decision has been taken to preserve it, infringed only by the present government’s development targets. In my view, such classification by landscape value should extend across a far wider swathe of what people generally regard as “the countryside.”

Agricultural land is already graded by its productivity and use. To this could be added its scenic and recreational value. Here there should be a strong presumption against development, even if regulation of existing buildings and land use might be more flexible than in national parks. Scenically valued countryside should retain its character under “rural conservation area” status, much as urban conservation areas do.

A lesser category of land might be that still classed as rural but of no significant landscape value. Again the phrase “presumption against development” would apply, but where there is no local call to retain it as rural, a change of presumption would be permissible. Planning authorities would be required to designate such land in their plans after local consultation.

Planners with whom I have discussed this believe it to be perfectly workable under existing law. Perhaps more significant, in light of the present conflict, the final category of “permissible” change of use would almost certainly yield more development than the present battlefield, where uncertainty leads only to legal argument and delay. The advantage to all—residents and developers alike—would be certainty about the future use and appearance of the countryside. The intention would be to save what is most valued, while yielding building land where appropriate within a plan. But the key must be its value as countryside, not pressure from developer interests.

How a society orders its living space is a symbol of its civilisation. There will always be conflicts over land since, as Mark Twain pointed out, “they’re not making it anymore.” Some societies resort to fighting. Some let rip and regret it. Some try in a cultured way to argue and resolve disputes. British planning has become a war zone to a degree I have not seen in my lifetime.

This has nothing to do with growth and even less to do with housing need. A crisis has arisen over the demands of a powerful lobby that has seen an opportunity in a government vulnerable to pressure. Yet the impact on the British countryside could be devastating, leaving it with the same visual ruination as across much of Europe. This would spoil the finest legacy that modern government has given the British people: a densely populated yet still gloriously rural landscape.