In the early hours of 9th November, at the tag-end of perhaps the most improbable election night in history, tens of millions of Americans who had spent a long night absorbed in a heart-stopping drama of Donald Trump’s astounding victory, staggered off to bed knowing one big thing: a revolution had happened. But what would come next? It was too much even for seasoned heads to fathom.

A 70-year-old washed-up television celebrity, with a dubious fortune made in real-estate and “branding,” had ridden a gift for rousing large crowds (which sometimes assumed the ugly character of mobs) into the presidency. Some candidates grow over time. Trump did too, but only in the sense that he got bigger—not wiser, not deeper, not better. At the end of the campaign, which began in June 2015, he continued to exhibit an almost brazen indifference to policy and governance—even to the ground rules of politics. He had exasperated handlers and advisers, declined even to do rudimentary homework for his debates with Hillary Clinton. More ominously still, he had dismally failed every attempt at governing himself—his appetites, his grievances, his thirst for vengeance, his childish need to have the last tweeted word.

But in 11 weeks, he will have to learn the rudiments of governing a country of some 320m citizens and at the same time become the leader in a world he has declared to be fraught with enemies or with allies undeserving of trust or even financial aid.

“If Donald were to somehow win,” Colin Powell, one of the few recognised living American statesmen had waspishly predicted in June, “by the end of the first week in office he’d be saying ‘What the hell did I get myself into?’” Two months and 120m votes later, many Americans, especially Beltway professionals—policy experts, diplomats, but above all the Republican legislators, some of whom had refused to endorse Trump—were wondering the same thing: what the hell had Trump, and they, gotten themselves into?

The first signs were tinged with surrealism. There was the rogues gallery of tarnished has-beens—former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, New Jersey governor Chris Christie, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich—now surfacing as possible Cabinet appointees, rehabilitated beyond their wildest dreams, rewarded for having scrambled on the Trump bandwagon months before in defiance of the party’s leadership. Another odd sight was the rejuvenated House Speaker Paul Ryan, who had antagonised Trump followers, including scores of Republican House members. All were up for re-election, which for Republicans means sharing a ballot with Trump. But in a conference call, Ryan had urged them to go their own way, though it would mean turning off voters whom Trump had excited.

There was talk of a post-election mutiny should Trump go down to defeat and the Republican House majority die with him. The opposite happened. Most defied Ryan, stuck with Trump, and his coattails lifted them to victory in rust-belt Democratic strongholds such as Michigan, Pennsylvania and Ryan’s own Wisconsin. Ryan, who at 46 exudes a much younger man’s quality of perpetual chastened buoyancy, avowed he was “ very excited” about teaming up with Trump. The President-Elect had “heard a voice out in this country that no one else heard,” and so achieved “the most incredible political feat I have seen in my lifetime.” “Donald Trump,” Ryan added, “will lead a unified Republican government. And we will work hand-in-hand on a positive agenda to tackle this country’s big challenges.”

This was shorthand for ruthlessly undoing every important thing Barack Obama has accomplished in his two terms. First up, as always, was the Republican vow, or fetish, to “repeal and replace” the 2010 Affordable Care Act, Obama’s controversial healthcare law, which extends coverage to some 20m who hitherto didn’t have it, but has caused monthly premiums to rise for many whose insurance isn’t covered by their employers, and yet earn too much for government subsidies. Some months ago, Ryan drew up his own conservative replacement plan. Trump, he implied, need only sign it, and the great deed would be done, with more undoing to come. “It’s not just the healthcare law that we can replace,” Ryan promised. “Think of the farmers here in Wisconsin being harassed by the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency]. Think about the ranchers in the west getting harassed by the Interior Department.”

This last was a glancing reference to a protest over the use of federal grazing lands, one of the more arcane causes of the Obama years, when Ryan and other libertarians depicted federal regulatory agencies as homegrown Gestapos terrorising honest citizens. Ryan’s press conference, it soon emerged, was a vehicle for putting forth his own agenda. If Trump went along, he’d get credit for the victory and endear himself to the Tea Party faction, if that is really what he meant to do. The fact that nobody, Trump included, knows whether that is what he wants is yet another sign of how blank a slate he is, and how unknowable the brave new world of American politics has become. Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader who is less ideological than Ryan and more mindful of the limits of legislative power, moved more cautiously. He too is keen to repeal Obamacare. It’s “a pretty high item on the agenda,” he said, and also part of “our commitment to the American people.” And no doubt he will lead the Senate in confirming a conservative appointment to the Supreme Court once Trump comes up with a name to fill the vacancy open since February. (McConnell and his fellow Republican Senators stubblornly resisted Obama’s pick, Merrick Garland, who will now enter the annals of footnotes and trivia lists).

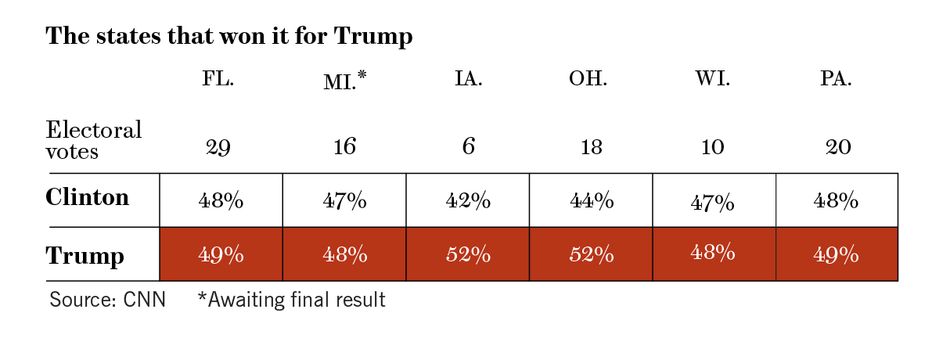

But otherwise McConnell will probably move more slowly, especially on Trump’s own extravagant campaign promises, which could prove very hard to keep. Some get into delicate matters of Constitutional law (for instance, Trump’s tinpot threat to investigate Hillary Clinton for her use of a private email server when she was Secretary of State). Others would require tampering with Nato agreements or rash changes in trade policy that most Republicans have insisted would be dangerous to America’s economic and national security interests. This category includes, first and foremost, Trump’s longstanding threat to build a wall along the Mexican border to keep out unwanted immigrants. The idea is opposed by Wall Street, corporate chieftains and Ryan himself. The same is true of Trump’s talk of imposing steep tariffs on China and rolling back major trade arrangements, both old (the North American Free Trade Agreement) and new (the Trans-Pacific Partnership). If Trump really means to do these things, he could find himself battling with his own party’s fervent pro-business contingent, which depends on donors in finance and the corporate world to fill the coffers of the Republican National Committee. The committee’s chairman, Reince Priebus, is, moreover, a Trump ally. Priebus also diverted a good deal of money and manpower into the “ground game” that turned out the pro-Trump vote in crucial states such as Florida and Ohio.

The stakes are even higher on issues like the Iran nuclear bargain painstakingly worked out by Obama and his Secretary of State John Kerry, but which Trump has sworn to undo since it is “one of the worst deals ever made by any country in history.” Even a smaller item such as his promise move the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—Israeli officials are already pressuring him to make good on it—is fraught with trouble given the volatility of the Middle East. But then Trump’s idea of foreign policy swerves rather dramatically from precedent. His favourite foreign leader, if not outright role model, is Vladimir Putin, who adores Trump in turn—or at least supposes him to be a useful idiot. How else to explain the apparently earnest efforts of Russian security, in alleged conjunction with Julian Assange, to hack into emails sent by the Clinton campaign? “How Vladimir Putin Won the US Election,” ran a morning-after headline in the News and World Report. (It is a mark of the singular strangeness of this election that Putin’s reported meddling scarcely damaged Trump at all, though most Americans loathe Putin and see him as heir to the Soviet monsters of the Cold War era.)

In any case, the glory of American politics is that questions of principle dissolve, most of the time, into the hard calculations of pragmatic politics. The most deft modern “legislative presidents”—Woodrow Wilson, the two Roosevelts, and Lyndon Johnson—were canny negotiators, “deal-makers” in Trump’s parlance. The difference is that they each also claimed a mandate. Today’s Republicans cannot. It is true that Trump’s victory was astounding and historic; for surprise, it ranks with Harry Truman’s comeback in 1948 and Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory in 1980. But in practical terms his win was narrow.

He lost the popular vote (as George W Bush did in 2000) and is in the anomalous position of a victorious candidate who did not carry his own state—in this case, New York, which he lost to Clinton by a prodigious million and a half votes. Trump’s majority in the electoral college was modest (he looks set for 306, compared to Obama’s 365 in 2008 and 332 in 2012). The same holds for the Republican Congress. The majorities in both Houses are flimsy. In the Senate, the advantage is too small to overcome (by cloture) the filibuster—the weapon the Republicans wielded throughout the Obama years. Should Democrats, under their leader, Chuck Schumer, likewise choose to obstruct, a good deal of Trump’s agenda could be stopped. Add to that his impatience, boredom with process, and notoriously thin skin, and Trump could find himself outmanoeuvred, outclassed—and out of office, either after a single term or, should he overstep his bounds, via impeachment. It has happened to far abler pros (Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton).

And this raises the most intriguing question about the new Trump presidency: how far might he go by making direct Caesarist appeals to “the people?” He has demonstrated an almost matchless talent for exciting his grassroots base, which remains—far more than his own party—the source of his strength. During the campaign he was happiest when in front of crowds, basking in adoration and reflecting himself back to the sea of Trump caps and T-shirts. Add as well his history of scapegoating and name-calling, and it’s not hard to see why so many, including, the New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, fear that Trump’s victory may endanger “democratic norms and the rule of law.”

Without question Trump sits atop the most powerful executive bureaucracy in history. What he proudly calls his “movement” begins in his powerfully adroit mobilisation of anti-establishment resentment, and deep class-based loathing of elites, the tide of authentic protest that swept him into office. Trump as agitator, cynical stirrer of ugly passions, remains a dominant theme on the left, which assumes that Trump’s supporters are either versions of the candidate himself or respond to his worst attributes. In a much quoted post-mortem, the New Yorker’s Editor David Remnick (the author of a biography of Obama), wrote, “That the electorate has, in its plurality, decided to live in Trump’s world of vanity, hate, arrogance, untruth, and recklessness, his disdain for democratic norms, is a fact that will lead, inevitably, to all manner of national decline and suffering.” By this reckoning, however, one could say Clinton’s supporters share her weakness for secrecy or feel beset by enemies, traits she has demonstrated for much of her career, and again during the election.

Either way, the depiction of Trump as aspiring strongman —as Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini or even Putin manqué—may exaggerate or misread the true nature of his ambition. Little in his history indicates either ideological mission or even a serious work-ethic. He seems closer to Silvio Berlusconi: his appetite is less for power than for celebrity and a kind of louche high-living. During his search for a running mate, when he was repeatedly turned down by big Republican names—most assumed he never had a prayer of defeating Clinton—one candidate, Governor John Kasich of Ohio, said Trump offered him a vast portfolio that would give him control over all foreign and domestic policy-making. Trump denied it. But it makes sense.

“He needs an experienced person to do the part of the job he doesn’t want to do,” said Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign manager at the time (since dismissed, partly because of his own questionable dealings with an oligarch in the Ukraine). “He sees himself more as the chairman of the board, than even the CEO, let alone the COO.” Colin Powell was probably right. Governing is tedious, demanding, unglamorous. Sometimes one has to share the credit or even deflect it on others. And when things go badly, no one else steps up to absorb the blame. What looks like victory can turn into defeat. An adoring public can pivot against you. How much more fun to be the entertaining front-man—not President Trump, perhaps, but “President Trump,” the star of his own government-subsidised nightly show, akin to the “Trump TV,” he was said to be contemplating should he lose to Clinton.

Instead, of course—and amazingly—Trump won. The reality show—the great barnstorming tour, with its hours of “earned media” (that is free television coverage)—has become reality, or will on 20th January, when he is sworn in by Chief Justice John Roberts, while the whole of America, and much of the world, looks on. It is a destination no one, beginning with Trump himself, expected to reach, which gives it a curious kind of innocence.

For the whole of its history, the United States has presented itself to other nations as an “experiment”—not just a country and a people, but a laboratory of democratic experiment. Its dynamism has inspired egalitarianism of a certain sort. Trump’s detractors get one big thing wrong. His presidency may prove to be a defeat or even disaster for democracy. But his election was a triumph, not only for the silver spoon which sat in his small infant mouth, but also for grassroots participation. He pulled off his feat with little outside money, a handful of advisors (mostly his children), a skeletal campaign, and only a fraction of the ground troops that Clinton had. In the last days, while she summoned moral support—from her husband, from the Obamas, from pop gods and goddesses like Bruce Springsteen and Beyoncé—Trump often seemed to be alone, shouting out into the void of his followers.

Each performance seems to have lifted him closer to victory, though he alone knew it. His supporters are overjoyed. In triumph he was unexpectedly subdued, maybe even alarmed. A strange isolating loneliness seems to haunt Trump and to have driven him joylessly on each furlong of his unorthodox quest. It will now follow him into the loneliest place of all.