We think we know David Hockney. He is one of the most recognisable and best-loved artists in the world—whether in his early incarnation as the boy from Bradford with bleached hair and round glasses who painted boys in swimming pools, or in his latter years as the trainer-wearing celebrant of East Yorkshire’s rolling landscape. His photo collage Pearblossom Hwy, 11-18th April 1986, #2 is the most popular image at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. His 1967 painting A Bigger Splash—with its meticulously realised explosion of white water in a scene of rectilinear calm—is regularly in the top 10 most popular British paintings. In 2011, British art students voted Hockney the most influential artist of all time.

On the one hand, Hockney seems reassuringly conservative in his focus on still life, landscape and portraiture. On the other, his bright-hued optimism and excited embrace of technology, from fax machines to the iPhone and iPad, have endeared him to new audiences. As two recent exhibitions at the Royal Academy—Yorkshire landscapes in 2012 and portraits in 2016—have proven, crowds flock to his abundant, inquisitive and joyful art.

In Hockney’s 80th year, however, Tate Britain is hoping to present a more comprehensive and nuanced account of his achievement in a new retrospective exhibition that runs from 9th February to 29th May.

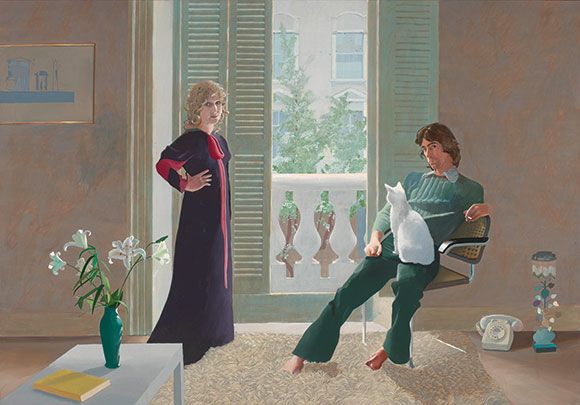

As the Tate’s Andrew Wilson suggests, overfamiliarity with a handful of images has inured us to the radicalism of Hockney’s work, and obscured the consistency that runs through it. “Is the Hockney of popular imagination—of A Bigger Splash and the double portraits—the real Hockney? Or is he more extended than that?” Wilson asked me. The opportunity to see works from private collections, some of which have not been on display for 30 or 40 years, will enable a more thoroughgoing exploration of the oeuvre. There will be recognisable icons such as Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, from 1970-71, which features the “it” couple of their day, textile designer Celia Birtwell and fashion designer Ossie Clark, the latter ruffling a fur rug with his toes as light streams into their elegantly under-furnished Notting Hill flat.

But there will be much more: exuberant cubist interiors and scroll-like landscapes from the 1980s; the Very New Paintings of the 1990s; etchings, drawings and photo collages; iPad drawings and the immersive landscapes of the 2000s; group portraits of card players from 2014 and the latest massive video works. “What I hope comes through,” Wilson says, “is this idea of Hockney as a quintessentially postmodern artist, incredibly virtuosic, marrying styles, moving between media, playful, mercurial. But also incredibly traditional, in a very radical, very contemporary way.” Wilson continues: “What has been absorbing him since he was a student in Bradford is this conundrum which preoccupies all painters: How do you represent the world of three or four dimensions, plus emotion, in two dimensions? This is the bedrock of his work.”

Hockney was born into a working-class, Methodist family in 1937. He recalls a school teacher scolding him, aged five, for trying to draw everything at once on one piece of paper. After four years at Bradford School of Art, and two years of National Service, he arrived at the Royal College of Art in London in 1959, where he found himself part of a talented cohort that set the tone for the Sixties’ art scene. His friends included the painters RB Kitaj, Allen Jones and Peter Blake. He first came to public notice at the Young Contemporaries exhibition in 1961, where he was labelled a pop artist. But rather than his embrace of popular culture, what was truly impressive was the quality of his draughtsmanship—whether an academic drawing of a skeleton he made in his first week at the RCA (instantly bought by an admiring Kitaj for £5) or the fierce and cheeky early paintings, with their expressive cartoon figures, asymmetrical compositions and painted numbers and letters.

A major Picasso exhibition in 1960, which Hockney visited eight times, was a profound influence, giving him licence to experiment with different styles and media, which he did with wit and imagination. He described his initial phase, in which his art chronicled his love affairs through references to Walt Whitman and Constantine Cavafy, as “homosexual propaganda.” Later, he experimented with different pictorial modes and emotional registers in works such as Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style, (1961), First Marriage (A Marriage of Styles I) (1962) and Play Within a Play (1963). Space is conjured and denied; three-dimensional figures coexist with flattened props; scene-setting is theatrical and anti-realist.

What he resisted then was abstraction, then dominant both in America and France. In one of many conversations over the last 10 years with the critic Martin Gayford, published as a book in 2011, Hockney recalled that “the American critic Clement Greenberg, who was very influential, announced, ‘It’s impossible today to paint a face.’ But de Kooning’s answer—‘That’s right, and it’s impossible not to’—always seemed to me to be wiser.” Alongside Kitaj, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, Hockney repudiated not just abstraction but also minimalism and conceptual art in favour of figuration. For him, this was a moral as well as aesthetic choice. Kitaj said that Hockney liked to quote WH Auden’s poem “Letter to Lord Byron”: “To me Art’s subject is the human clay.” More recently, Hockney told Gayford: “There are lots of people who tell you they are making art. Maybe some of them are, but I’m not sure that’s true for all of them. Perhaps I’m old fashioned, but that’s not a phrase I would use. I’d prefer to say I’m making pictures—depictions.”

But pictures did not just mean painting. From the start, Hockney experimented with different media. In 1961, he made his first etching, initiating a period of intense print-making that lasted until 1964, resulting in his precocious print series, based on Hogarth, entitled A Rake’s Progress (1961-63). Lyndsey Ingram, a print dealer whose show David Hockney: The Complete Early Etchings 1961-1964 opens at the Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert gallery on 3rd February, has long been an admirer of these early works. “The material is very raw, it is very accomplished,” she says.

In contrast with the etchings’ scratchy graphic energy and monochrome literariness, the paintings Hockney made in America in the 1960s are ecstatic with light and colour, cool and flat, revelling in sleek geometries and the smooth finish of acrylic paint. The satirical depiction of collectors frozen between their Le Corbusier chairs and William Turnbull sculptures on immaculate verandahs is balanced by the sensual pleasure conveyed by his paintings of young men in shimmering pools.

In 1966, Hockney was invited to design the sets and costumes for a production of Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi at the Royal Court, the first of many stage designs. It was an opportunity to explore the creative possibilities of three-dimensional space with real people performing within it. A year later, he acquired a 35mm Pentax camera, which inspired him to create a series of paintings of greater naturalism—even photo-realism. Hockney later said of this period: “To me, moving into more naturalism was a freedom.” This led to a renowned series of double portraits featuring friends of Hockney, including Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, and Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott. These paintings reveal Hockney’s admiration for Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico and other old masters; but they also mark his commitment to painting about his personal life, and to the task of finding ways to express not just optical, but also psychological realities. Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy represents the peak, however, of Hockney’s journey towards what he later called “the trap of naturalism.”

"In confronting photography's apparent monopoly on truth, Hockney was engaging with painting's existential crisis"This coincided with the end of Hockney’s relationship with Peter Schlesinger, spurring a new period of travel. He moved to Paris, reverted to oil paint, and began to interrogate the constraints of single-point perspective as offered by the camera. As he would say later, “photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops—for a split second. But that’s not what it’s like to live in the world, or to convey the experience of living in the world.” In confronting photography’s apparent monopoly on truth, Hockney was engaging with the existential crisis that has afflicted painting since the earliest photographs were produced in 1839. Ironically, however, it was the camera that offered a way out.

In 1982, Hockney began to experiment with photographic collages, exploring how combining images created from multiple viewpoints of the same scene could evoke the experience of being in a space as vast as the Grand Canyon or of sitting in a room playing Scrabble. It was, after all, collage and cubism that had offered Picasso and Georges Braque a way to incorporate time and space into their revolutionary paintings. An encounter in 1984 with Chinese scrolls offered another alternative to the single-point perspective of western art since the Renaissance.

A series of gorgeously-coloured rolling painted landscapes emerged from Hockney’s studio, evoking his daily drive from the hills above LA to his studio. Hockney would even take visitors on this drive in a kind of performance adjunct to the paintings—encouraging them to see the world vividly, and in multiple dimensions.

Since the last Tate retrospective in 1988, Hockney’s technical investigations have continued in parallel with a prodigious output of paintings, drawings, photography, stage design and experimental video. In 1999, he was prompted by an exhibition at the National Gallery to conclude that Ingres must have used a camera lucida or other similar device to construct his paintings. The resulting book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, published in 2001, argued that since the Renaissance many great artists had used lenses and mirrors to compose their spaces—creating a 2D representation of a 3D world, as if they had used a camera.

As Hockney explained two years ago, in a recent catalogue, the problem with perspective generated in this way is that it excludes the viewer. By contrast, the perspective in Chinese art “does not have a vanishing point. If it did, it would mean you have vanished.” The difficulty, he suggests, is the foreground: “there is always a void between you and the photograph.” He added: “I am taking this void away, to put you in the picture.”

It is this impulse that lies behind the stupendous body of work he produced in Yorkshire in the 2000s and, after the death of a studio assistant in 2013, in Los Angeles. The landscapes’ luscious paintwork and ingenious construction of space lure you in. The curious group scenes of card players or dancers or people in a room, with their use of reverse perspective, invite our participation in the joyful act of looking, while the portraits excite us with their formal discipline and psychological insight. As Andrew Wilson remarks, Hockney’s lifelong exploration of the technical aspects of depiction, “involves a real generosity towards the viewer.” For, Wilson adds, “He wants people to be engaged with his work. He wants their eyes and feelings to be drawn into it.”

And it is this commitment to the present moment, and his unrelenting pursuit of the best means to communicate visually a complex web of sensations and emotions, that is his unique gift and genius.