U-turns are a staple of politics, in all but the most honeymoon phases of governments. But Chancellor Philip Hammond's U-turn on his Budget plan to raise National Insurance for the self-employed is a very unusual one, combining as it does a very firm defence of the need for the policy with the decision to scrap it.

That we have ended up in that place reflects the undeniable fact that the politics of the increase in self-employed National Insurance contributions (NICs) has been a disaster, while the policy rationale remains absolutely undeniable. To put it another way, whatever the rights and wrongs of breaking the spirit of manifesto commitments—be it tax rises, migration targets or membership of the single market—the substance of the Chancellor’s U-turn on NICs means the government has missed an opportunity to correct a big structural flaw in our tax system.

This matters both for fairness and for the public finances.

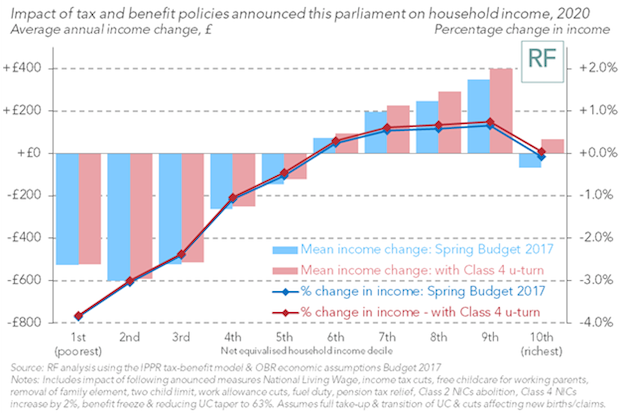

On fairness, the U-turn means the next few years will now actually see a growing tax gap between employees and the self-employed, at the same time as the benefits gap between the two is closing significantly through the introduction of the single tier pension that gives the self-employed the same pension entitlement as employees. The self-employed do need more support in other areas, including with pension saving and maternity pay, but those do not come close to justifying the tax gap with employees.

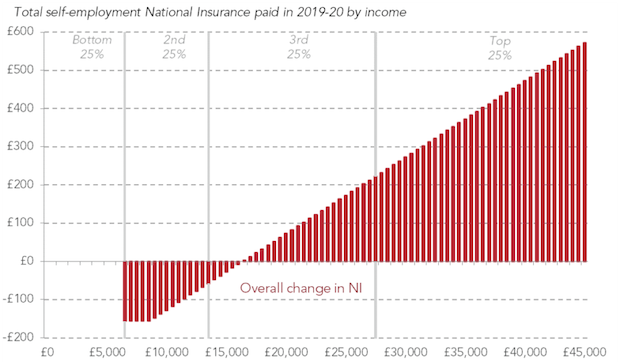

We should also be clear that the package of NICs reforms due to come into effect from next April would have left the majority of self-employed workers better off—including two-thirds of self-employed women.

Yes, there were going to be losers—as is always the case with tax rises—and no politician should ever be flippant about the very real impact tax rises (or indeed benefit cuts) can have. But this was a progressive tax rise—the majority of revenues would have been raised from the richest ten per cent of households.

On the public finances, today’s U-turn means the total cost of lower NICs for the self-employed will now grow from £5.1bn this year to an estimated £6.2bn in 2019-20. These are big sums, dwarfing the actual size of the proposed tax rise. More broadly, it is worth reflecting that if this is the fate of small progressive tax rises—with a good number of MPs of all parties now apparently opposed to the substance not just the manifesto breaking part of this story—then we’re in for a trickier time in terms of balancing the books or funding our public services in a fair way.

The undeniable strengths of the fairness and public finance arguments is why it is welcome that both the Chancellor and Prime Minister remain committed to addressing this tax gap. They will just have to do so on the other side of the next election. The work to make that possible will hopefully dovetail with the wider and welcome thinking that the Taylor Review is doing on how policy can keep up with modern working practices.

For those focused on the big picture challenges facing Britain in the next few years, the real living standards story is that, while a small and sensible piece of tax reform that affects higher income households has been shelved, the government is pressing ahead with benefit cuts that leave low and middle income households facing a far greater hit in the years ahead. As the chart below shows, the combined impact of tax and benefit policies over the parliament remains large and highly regressive. For those wanting to focus on policies the government should be engaging in a more traditional U-turn on, this is them.

The last week has not been the best one for the Chancellor—and more importantly nor has it been for progressive policy making, or indeed tackling the huge living standards challenges facing low and middle income households. In time the Chancellor clearly plans to rethink his rethink on National Insurance. He is right to do so and perhaps, after the week he has had, he can also reflect on the wisdom of his predecessor on making manifesto commitments to not increase taxes at a time when the public finances remain challenging and the pressure on public services is growing. After all in politics, as well as life, we all live and learn.